It is a rare opportunity to be given a curatorial blank slate like the one that has been handed to the Wallace Collection for Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company. The exhibition’s 109 works belong to the relatively unexamined genre of Company Painting. These are works created in India by Indian artists but commissioned by East India Company (EIC) officials, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, who wanted to record the flora, fauna and daily scenes of their new home.

Established in the 17th century, the EIC was a privately owned company initially conceived as a trading body for Asian goods. By the early 19th century it had claimed territory over large parts of the Indian subcontinent, aided in part by a weakening Mughal Empire. Having increasingly become an imperial arm of the British government, it ceded its territory in 1858 to the newly established British Raj. As a result, these paintings embody elements of both East and West, curious fusions that engender comparisons from the flattened landscapes of Eric Ravillious to the exquisite detailing found in Persian miniature tradition. But rather than being embraced by both countries, the works’ liminal position has left them historically misaligned. In fact, despite a bulk of the genre’s masterpieces lying in British institutions (key loans will come from the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum), they have never received a dedicated exhibition in the UK until now.

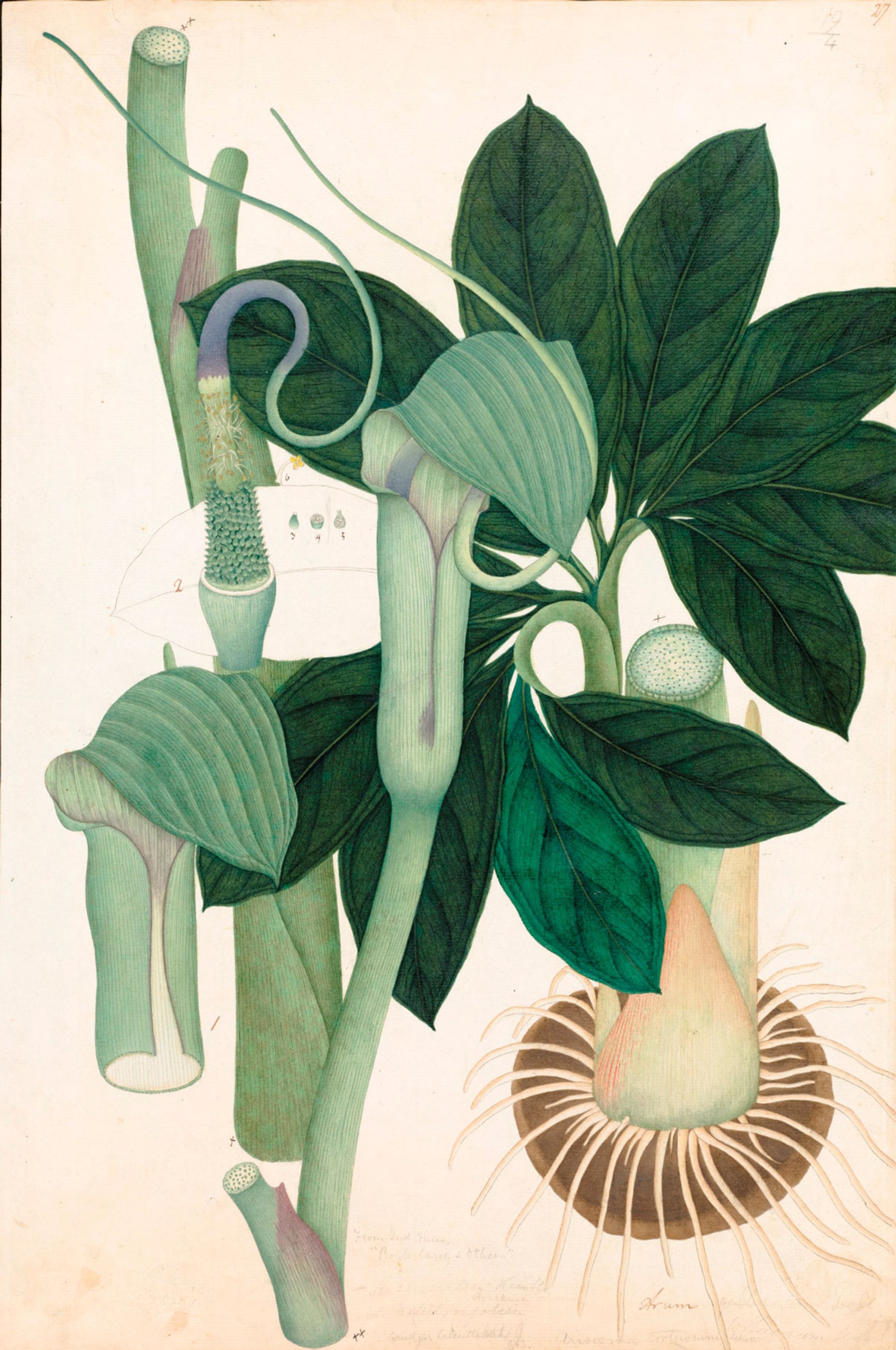

Arum tortuosum, Vishnupersaud (c. 1821) © The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

“No one knows what to do with the stuff,” says the writer and historian William Dalrymple, who has curated the show. “Western institutions are wary to touch it, they’re terrified of the ‘c’ word.” Not only does the tricky legacy of colonialism leave Company Painting unappreciated in the UK, British patronage is also viewed unfavourably in India, where the nationalistic canon favours art from the High Mughal and Modernist periods.

“These works have been influenced by centuries of traditional Indian art, before dying at the twin hands of colonial art schools and photography, which rendered drawings for botanical studies obsolete,” Dalrymple says. “As such, this style of painting has dozens of ancestors but no real heir.” To revitalise interest, he has shifted the focus away from the European commissioner to the indigenous artist, treating them as individuals rather than nameless artisans belonging to local schools.

The exhibition is broad in both its geographic span and the subjects it presents, from miniatures by imperial Mughal painters such as Ghulam Ali Khan to equine paintings by Shaikh Mohammad Amir of Karriah.

Many of the works come from reputed compendiums of Indian life, often known as "albums". Thirty works from one such collection, commissioned by Mary Impey, the wife of the chief justice of Bengal, are being shown together for the first time since they were split up in the 18th century. They notably include the work of the Bengali artists Sheikh Zain ud-Din, Bhawani Das and Ram Das, depicting (often life-sized) animals and plants.

Great Indian Fruit Bat (around 1777-82), painting attributed to Bhawani Das Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Painted with European watercolours on English Watman paper, their blank backgrounds and subject matter align them to Western naturalist paintings, but they contain decidedly Mughal influences in their colouring and perspective. The personality imbued into many of these works also elevates them beyond strictly scientific portrayals, sometimes to amusing effect. Great Indian Fruit Bat (around 1777-82), attributed to Bhawani Das, combines the fine details of the bones of a bat's wings with a curiously flattened penis and an inviting stance, which the exhibition's catalogue compares to a commendatore ushering a woman into a Venetian opera.

Although their exhibition history is limited, works from collections such as the Impey Album have a strong place in the market—a single page can fetch over £300,000 (with fees) at auctions. Other works on show, however, have been rescued from near total obscurity. Dalrymple says during his preparation for the exhibition he received a call to notify him of thousands of unrecorded botanical works lying in storage at Kew Palace, including paintings by the largely unknown artist Vishnupersaud.

The Wallace Collection’s director, Xavier Bray, says that he hopes the show will highlight the long history of cultural co-operation between the UK and India and help foster partnerships between Indian donors and UK institutions. To this end, the exhibition is sponsored by DAG, a commercial gallery with locations in India and New York, specialising in Modern Indian art.

“Although we find it difficult to discuss our colonial past, it is necessary in order to move forward,” Bray says. However, the show will stop short of making explicitly political points regarding the barbaric nature of the EIC and its actions in India. Despite being spared no detail in Dalrymple’s recent book, The Anarchy: the Relentless Rise of the East India Company, Bray says that UK institutions are “still in the early stages of figuring this stuff out”. He adds: “What we hope this show can be is the first step in a larger conversation around understanding the political context of our colonial past.”

• Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, Wallace Collection, London, 4 December-19 April 2020