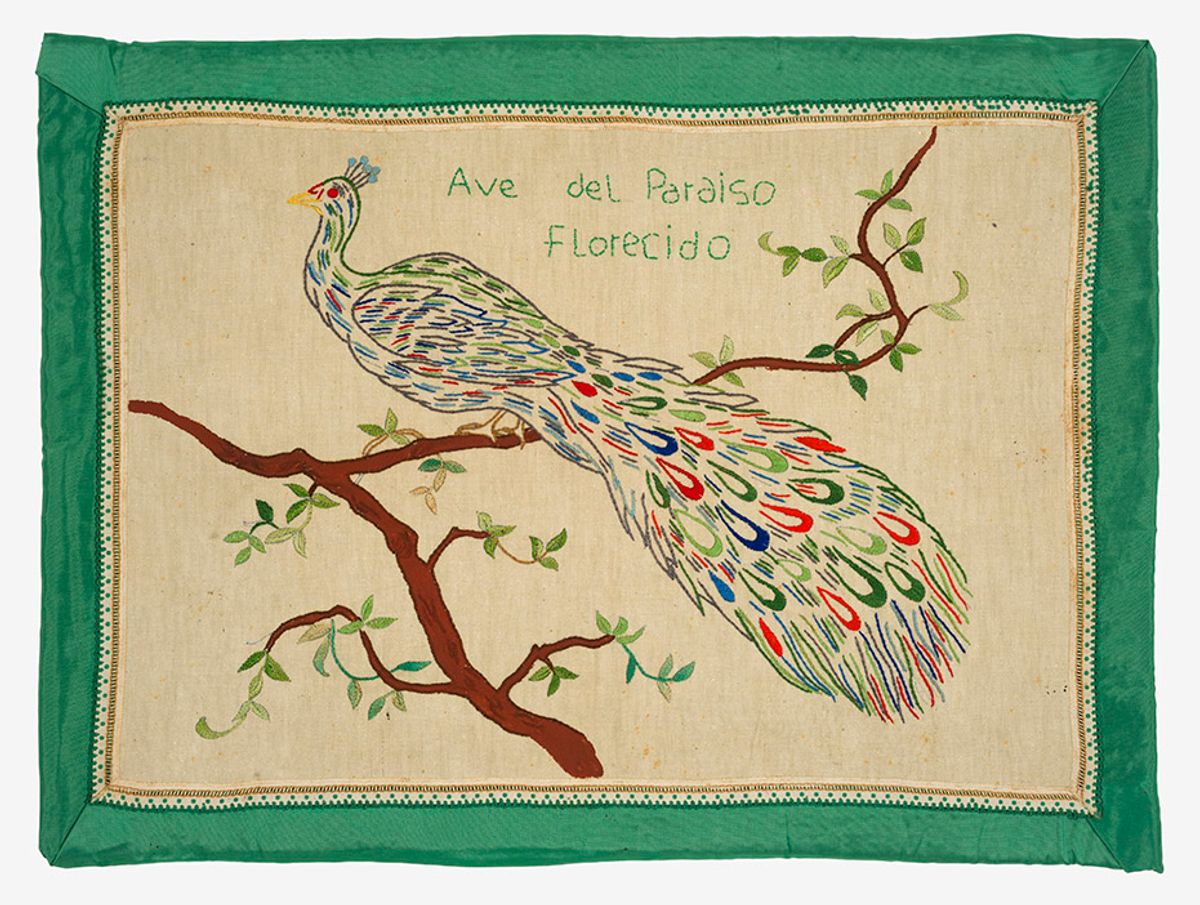

I Am Awake at Cecilia Brunson Projects (until 13 December; free) is the first UK solo show of the Paraguayan artist Feliciano Centurión. A double debut, many of the exhibition's works are being shown to the public for the first time, having spent the last 20 years hidden away in an unopened box at Centurión’s family home. According to Cecilia Brunson, the gallery’s founder, Centurión, who died aged 34 of AIDS in 1996, instructed the box to be opened "when the time felt right". Inside, Brunson found a collection of small blankets on which Centurión, in the last years of his life, had crocheted patterns and creatures from his homeland onto brightly coloured backgrounds. Shown alongside dinosaur figurines collected from Argentinian street markets and decorative paper plates, they combine the tragic reality of his disease with a kitschy and whimsical sensibility. Several works were made in collaboration with fellow South American artists associated with the Arte Light movement. For Centurión and his peers (80% of whom died of AIDS-related illnesses), the private and the political were often blurred as their very existence became politicised by a government that sought to erase their identities. On many of these household textiles, Centurión had hand-stitched phrases, mantras he must have repeated to himself like prayers to process his fate. "Death is a recurring part of my life", reads one. To look upon it is not to understand just his fear, but to feel his defiance too. These later works prove that beauty can spring forth from the darkest moments, locating Centurión's legacy in his bravery, and serving as a battlecry for future generations.

Valie Export changed her name aged 28 as a means of breaking away from what had come before. Eschewing both her family surname and that of her first husband, she adopted a new one from a cigarette packet. Export came about in the wake of the Vienna Actionists but hers was, and still is, a decidedly feminist brand of work. Her early performances, such as Tapp und Tast Kino (1969), where she invited the public to touch her breasts through a box over her torso, are hallmarks of the cannon now, but would still shock many. In 1980, Export represented Austria at the Venice Biennale, alongside the painter Maria Lassnig. This week, The 1980 Venice Biennale Works, recreating Export’s Venice installation opened at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac (until 25 January 2020; free). For fans of Export’s work, the show is a welcome historical exhibition (sadly sans Lassnig) that also includes archival documents and is a fascinating time capsule. Among the works on show are the famous Geburtenbett (1980) with its spread legs, red neon and video of a Catholic mass—which received a “so-so” reaction at the time according to Export—and the visceral ...Remote....Remote... (1973), a video of her removing dead skin from her fingernails—an extreme manicure of sorts—using a Stanley knife.

Last year Marcin Dudek made a to-scale recreation of a makeshift gym, originally built in the 1990s by his crew of football hooligans in the basement of a Krakow council estate. Now the centre-piece of Akumulator at Edel Assanti (until 20 December; free), its rusted steel frame brings the raw, subterranean aesthetics of an Eastern European fight club into the gallery space. Here, we are immersed in a post-Communist moment where, in the absence of other outlets of self-expression, a hyper-masculine culture manifested itself among a generation of lost men. Accordingly, through repurposing neglected materials, Dudek uses found objects to gives a hunter-gatherer-like utility to the works, fashioning the corrugated metal from radiators into large barbell weights and his own leather jacket into a punching bag with its stuffing viscerally busted out on the floor below. On one ‘wall’ of the gym hangs a cloth tape collage in which hundreds of images, taken from online forums where men brag about their own DIY gyms, are criss-crossed together in reference to Piranesi’s 18th-century geometric prison drawings. But this gym is not a place of entrapment, it is a community-built space that functions as an "an alternative pathway for crime-driven youth... a model for survival". Dudek might well be critiquing a crisis of masculinity here, but equally he celebrates the group bonding that occurs in situations of hardship—that deeply human impulse to form communities under any circumstance.