The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York has launched a digital archive of 60,000 objects related to the life and career of Noguchi (1904-1988), including letters, photographs, manuscripts, project records and architectural drawings that shed light on the Japanese-American artist’s thinking and his collaborations.

At the same time it has updated its online catalogue raisonné for the artist, expanding it to around 5,000 works spanning six decades. The catalogue, which first went online in 2011, now reflects deeper research into Noguchi’s lesser-known early work of the 1920s and 1930s, when he was mostly a figurative artist. “A lot of people don’t know that figurative works were his bread and butter before he moved toward abstraction after 1940,” says Brett Littman, the museum’s director.

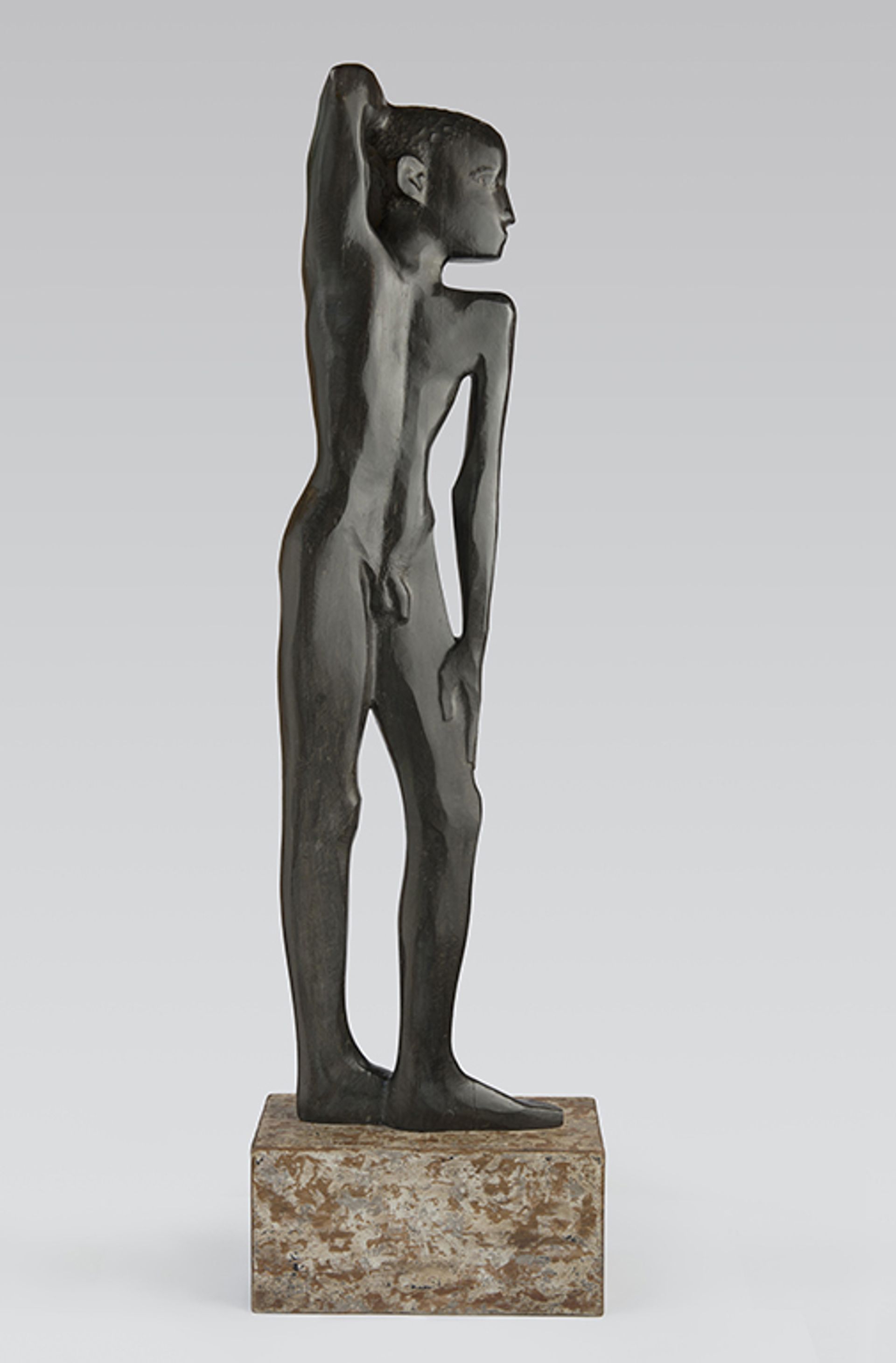

Among the discoveries is Black Boy from around 1934, a large figure that Noguchi carved from a single piece of ebony wood that was acquired by George Gershwin and has remained with his family ever since, says Alex Ross, the managing editor of the catalogue raisonné. Littman says the catalogue also boasts a bibliography of each article in which a featured work has been discussed.

Isamu Noguchi, Black Boy (Figure), from around 1934 Ben Blackwell/© Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/ARS

Among the riches of the archive are over 28,000 photographs documenting Noguchi’s art, exhibitions and studios as well as the people he met and worked with on his international travels. “He’s like Zelig: he keeps popping up in all the intellectual and social circles in New York and around the world,” the museum director says. “It’s like a who’s who.”

Users can search the archive in categories like photography, manuscripts, architectural material, business and legal documents, Noguchi Fountain & Plaza (the artist’s design company) and press-related items.

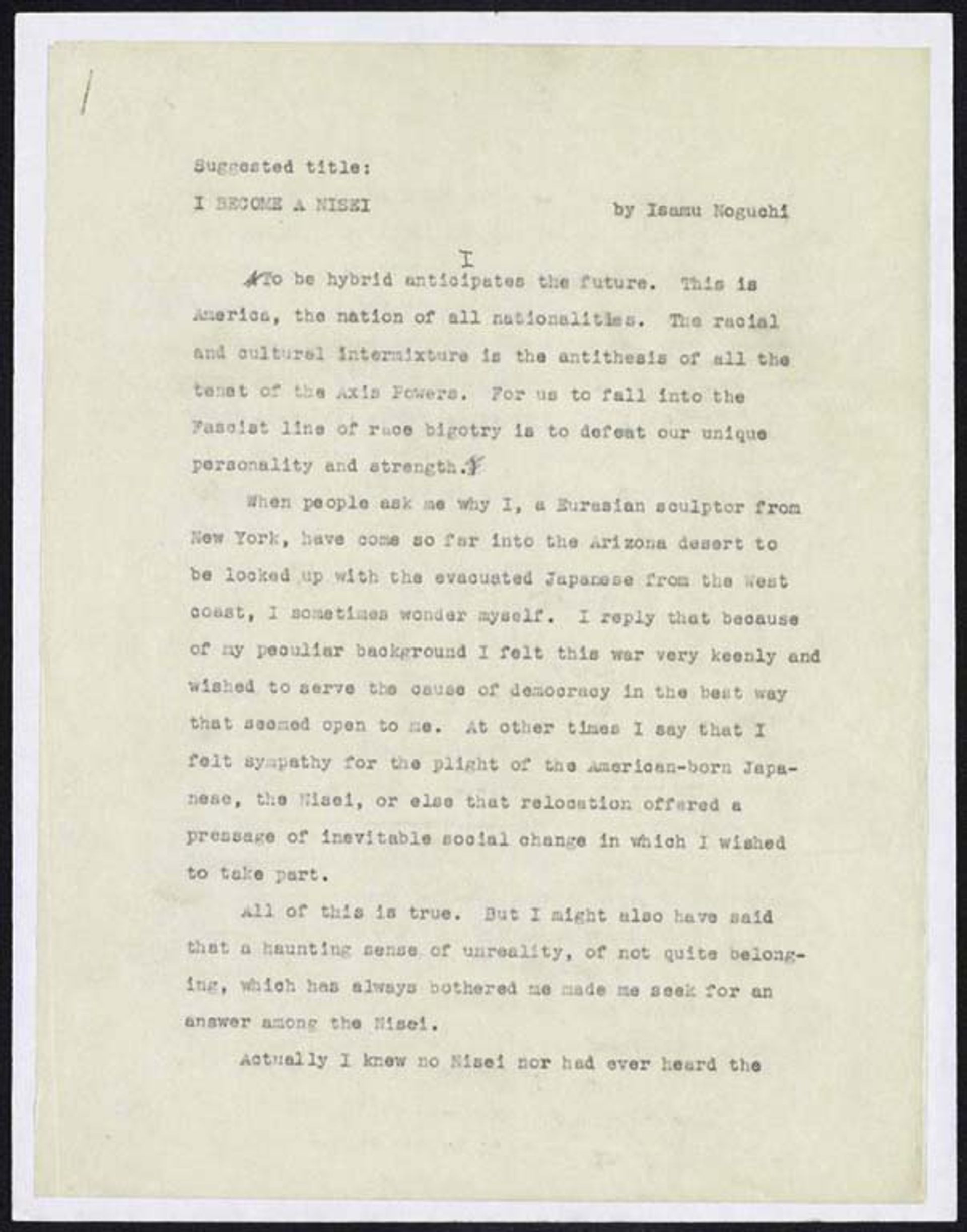

Among the more compelling manuscripts that visitors can peruse online, Littman says, is I Became a Nisei, an article that Noguchi wrote while living in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans in 1942 in Arizona. A tool allows users to zoom in on the typewritten words on 12 pages as well as changes made with a pencil.

“When people ask me why I, a Eurasian sculptor from New York, have come so far into the Arizona desert to be locked up with the evacuated Japanese from the West coast, I sometimes wonder myself,” Noguchi writes. “I reply that because of my peculiar background I felt this war very keenly and wished to serve the cause of democracy in the best way that seemed open to me.” Littman said that Noguchi visited the camp to offer his services as an architect and ended up being interned.

A letter that Isamu Noguchi wrote from an internment camp for Japanese-Americans in 1942 Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

The artist was born in California to a Japanese father and American mother and spent much of his life feeling the pull of both East and West as he navigated the globe.

The archive was assembled in a three-year effort that was jump-started through a lead grant from the Henry Luce Foundation. Over the next few years, the museum hopes to adds thousands of additional items, Littman says, including more documentation about the artist’s environmental works, like letters and contracts for the 1959 garden that Noguchi designed for Unesco’s headquarters in Paris. The museum also hopes to add video clips in which the artist appears.

“It’s an incredible resource,” Littman said of the archive and catalogue. “It’s a great way for people to dip their toe in and understand the kaleidoscopic nature of the Noguchi project, which was about so much more than making sculpture.”