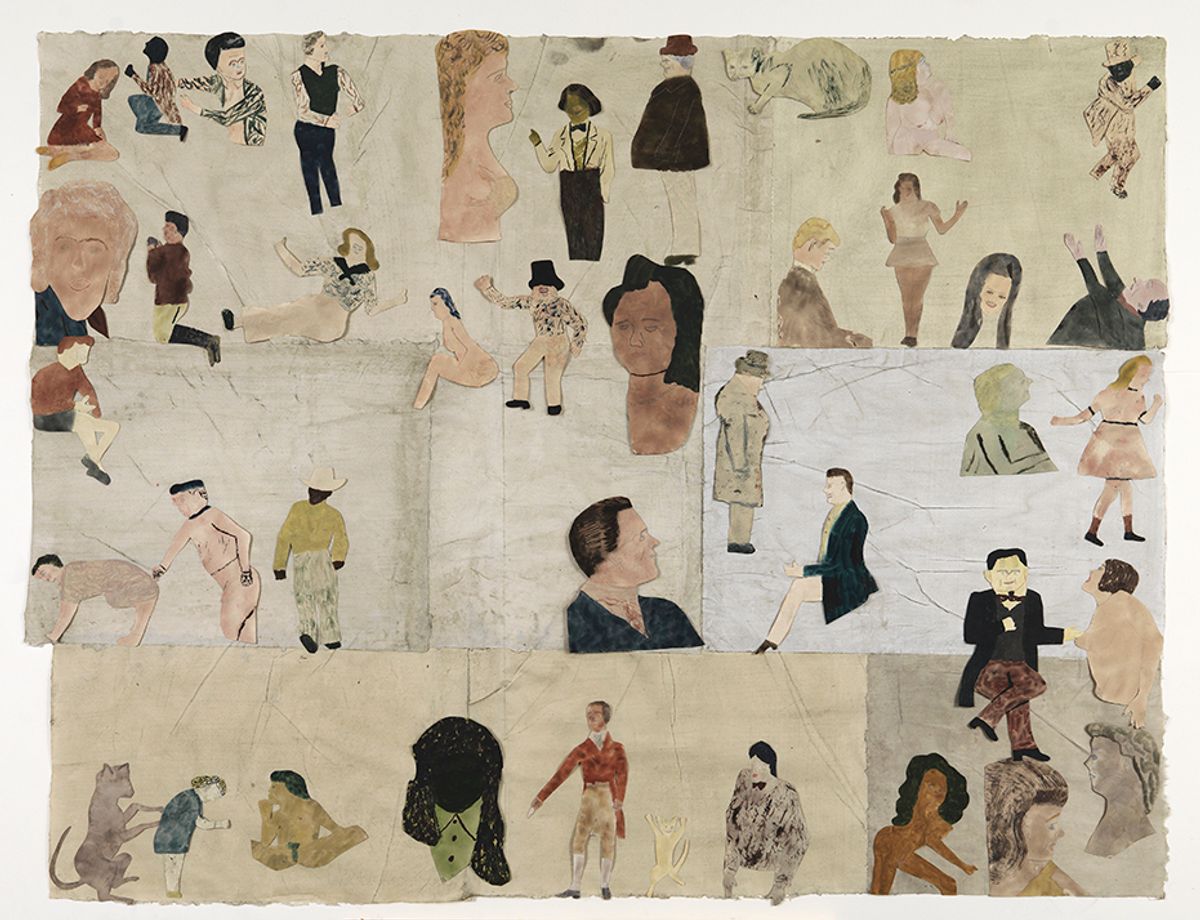

Jockum Nordtström's works in The Anchor Hits the Sand at David Zwirner (until 19 December; free) are rooted in childhood experience. Not in its naïvety or innocence, but rather the intense and confusing way it feels to inhabit a world that one has not yet ordered or figured out. Nordtström, who works mainly on paper, shows new collages and pencil drawings of absurd scenes inhabited by familiar-looking yet strange characters. Bell-bottomed sailors, human-sized cats, top-hatted men and naked figures are all painted, drawn, cut-out and arranged to mimic the clumsy dexterity of an eight year old. In one drawing, two men stand above a third who lies at the bottom of a set of stairs, yet nothing hints at what might have happened prior. Try as you might, it is impossible to locate anything here. Occupying a whole room upstairs is the debut of a large shadow puppet installation, where figures float and dissolve on a thin patchwork paper screen. Nordström willingly shows us his hand and invites viewers to observe the mechanics behind the screen. Yet, just like in his works on paper, the strange logic these characters are governed by leaves us unable to completely grasp the bigger picture. Everything remains as a series of vivid but unrelated vignettes, the whole truth just out of reach.

Earlier this year, Leo Villareal brought cutting-edge LED technology to London's bridges in an ongoing project to illuminate the Thames. Now, for his new show at Pace (until 18 January 2020; free), he uses this custom software to create light displays upon a series of panels with surprisingly reflective results. The show's central work Detector (2019) measures at more than 10m. Its swiftly moving constellation-like patterns evoke the cosmos, so mesmerising to watch that it is easy to read this as a mere visual spectacle, akin to a fireworks display. But Villareal is concerned as much with the micro as he is with the macro and encourages us to get up close. Observing the individual flashing binary light units which make up these pieces, we begin to see the sublime in the man-made and the minute that governs the universal. By playing on scale, each of these works of masterful artistic coding encourage us to see the world as both infinitely small and large.

Visitors to 180 Strand could be forgiven for forgetting they are in central London when they experience Other Spaces (until 9 December; free), a trio of immersive installations—the largest of which surrounds the viewer with sounds from ecologies as remote as the Arctic tundra. The Great Animal Orchestra (2016), an audio-visual work that here makes its UK debut, consists of animal noises from an archive of recordings collected over the past 50 years. A collaboration between United Visual Artists (UVA) and the US musician and naturalist Bernie Krause, the piece is an ode to the beauty of the natural world, a bio-acoustic piece that “is as carefully orchestrated as humanity’s most complex musical scores”. Electronic spectrograms, created by UVA, provide abstract visual interpretations of the natural environments represented. “It is rare for the visual element of a work to be secondary to its audio; we have turned the typical museum installation model on its ear,” Krause says.