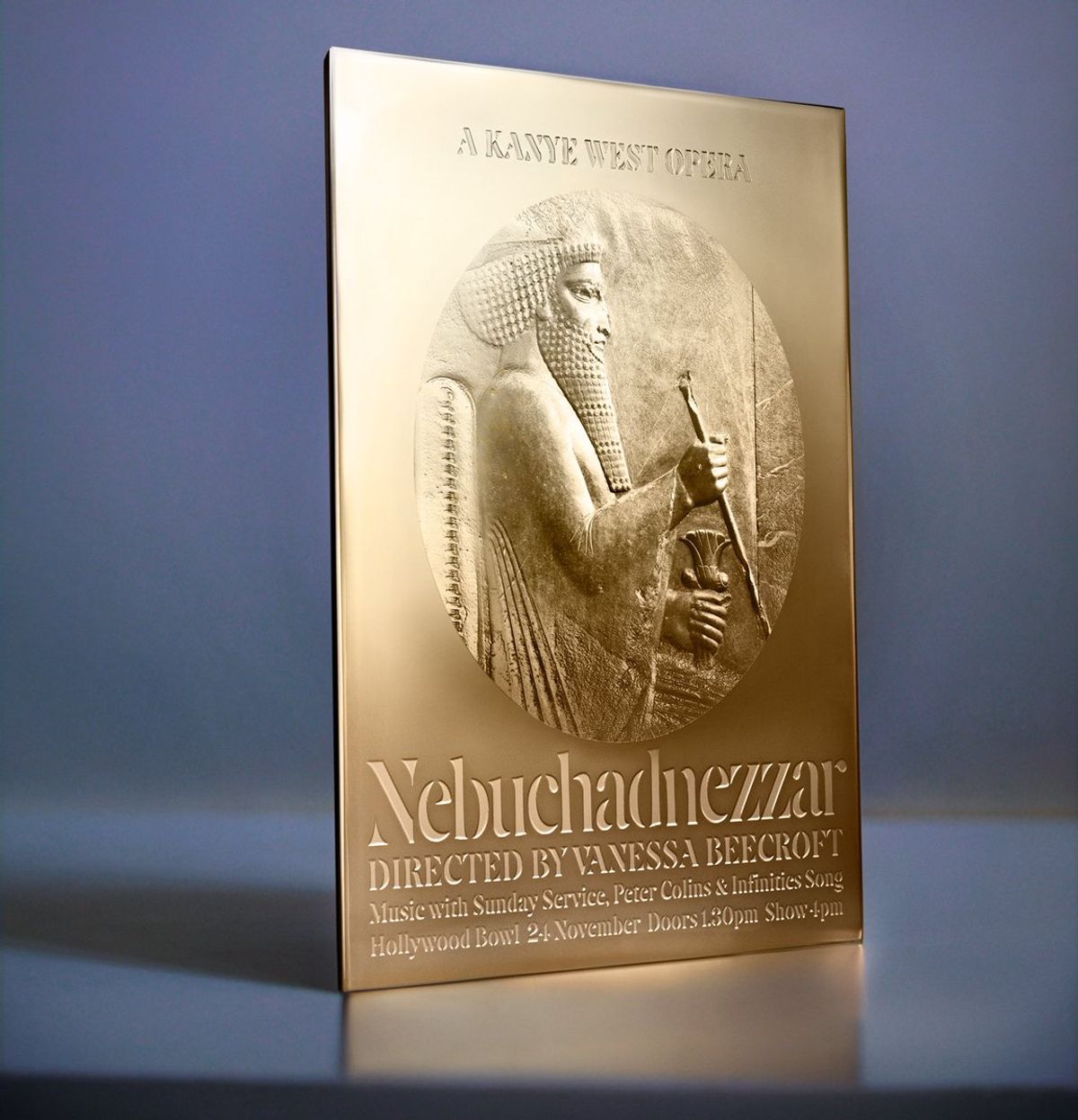

It is difficult to take one’s eyes away from the invitation to Nebuchadnezzar, Kanye West’s forthcoming opera at the Hollywood Bowl on 24 November. For some, it might have to do with its looking like a dazzling plate of solid gold. For those with even a smattering of knowledge of Iranian history, however, it’s more likely because the figure featured on the invitation—which West revealed to his Twitter followers over the weekend—is not Nebuchadnezzar II, the opera’s Babylonian namesake, but Darius the Great, one of Iran’s most storied rulers.

In designing the invitation, the artist Nick Knight used a photograph of a well-known relief of what is presumed to be the emperor Darius from the Achaemenid Persian capital Persepolis in southern Iran, in which the emperor appears seated on a throne with a lotus in one hand and a sceptre in the other. Yet, neither West nor Knight has made any mention of Darius or the relief’s Iranian origins, nor do any credits appear on the invitation in the tweet.

Darius I, centre, as depicted on a relief from Persepolis, now in the Archaeological Museum in Tehran. Courtesy of Livius.org

Aside from the issues of historical inaccuracy on the part of West and Knight and their not giving due credit, the use of Darius’s image is particularly problematic when considering who he and Nebuchadnezzar were. During his reign as the most prominent ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nebuchadnezzar sacked Jerusalem and brought a group of Jews back with him to Babylon as captives. These Jews remained oppressed there until their liberation at the hands of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire. Praised by Greek writers like Xenophon as the ruler par excellence and the only Gentile to be referred to as a messiah in the Bible, the ever-tolerant Cyrus not only gave the Babylonian Jews leave to return to the Kingdom of Judah but also allowed them to flourish in the empire during his reign.

Following in his predecessor’s footsteps, Darius, too, was known for his kindness towards the Jews (he helped them restore the Second Temple) and his respect for the many creeds and religions of the Persian Empire, which, while he ruled, extended from Greece to India. As such, in using Darius’s likeness in lieu of Nebuchadnezzar’s, West and Knight have both misrepresented Nebuchadnezzar and—as in the way many of Trump’s supporters have emphatically compared the president to Cyrus—conflated oppressor with liberator.

William Blake, Nebuchadnezzar (1795–around 1805) Courtesy of Tate

Even though the relief was probably chosen for largely aesthetic purposes, the use of it in such a context is inexcusable. Why did West and Knight not instead use William Blake’s 1795 watercolour painting-cum-print of Nebuchadnezzar, for instance, or one of the 17th-century English tapestries depicting the prophet Daniel’s interpretation of the king’s dream? Better yet, West could have commissioned an artist to produce original artwork for the invitation. Using an image of Nebuchadnezzar himself would have spared Darius’s (and Cyrus’s, for that matter) memory such an affront, and also helped avoid exacerbating existing misconceptions of historical Iranian art, which today is often incorrectly attributed—even in academic contexts—to that of neighbouring peoples and cultures.

All one can hope for at this point is that the opera itself won’t further make Darius roll in his grave.