The Currier Museum of Art says it has acquired a second house in Manchester, New Hampshire designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, one of just seven so-called Usonian Automatic glass-and-concrete houses sketched out by the architect.

The museum’s director, Alan Chong, says that an anonymous donor furnished $970,000 to purchase the 1957 home, which had been listed with an asking price of $850,000. The original owners, Dr Toufic Kalil and his wife, Mildred, had died in 1990 and passed it on to one of the doctor’s siblings, John Kalil, who died last year.

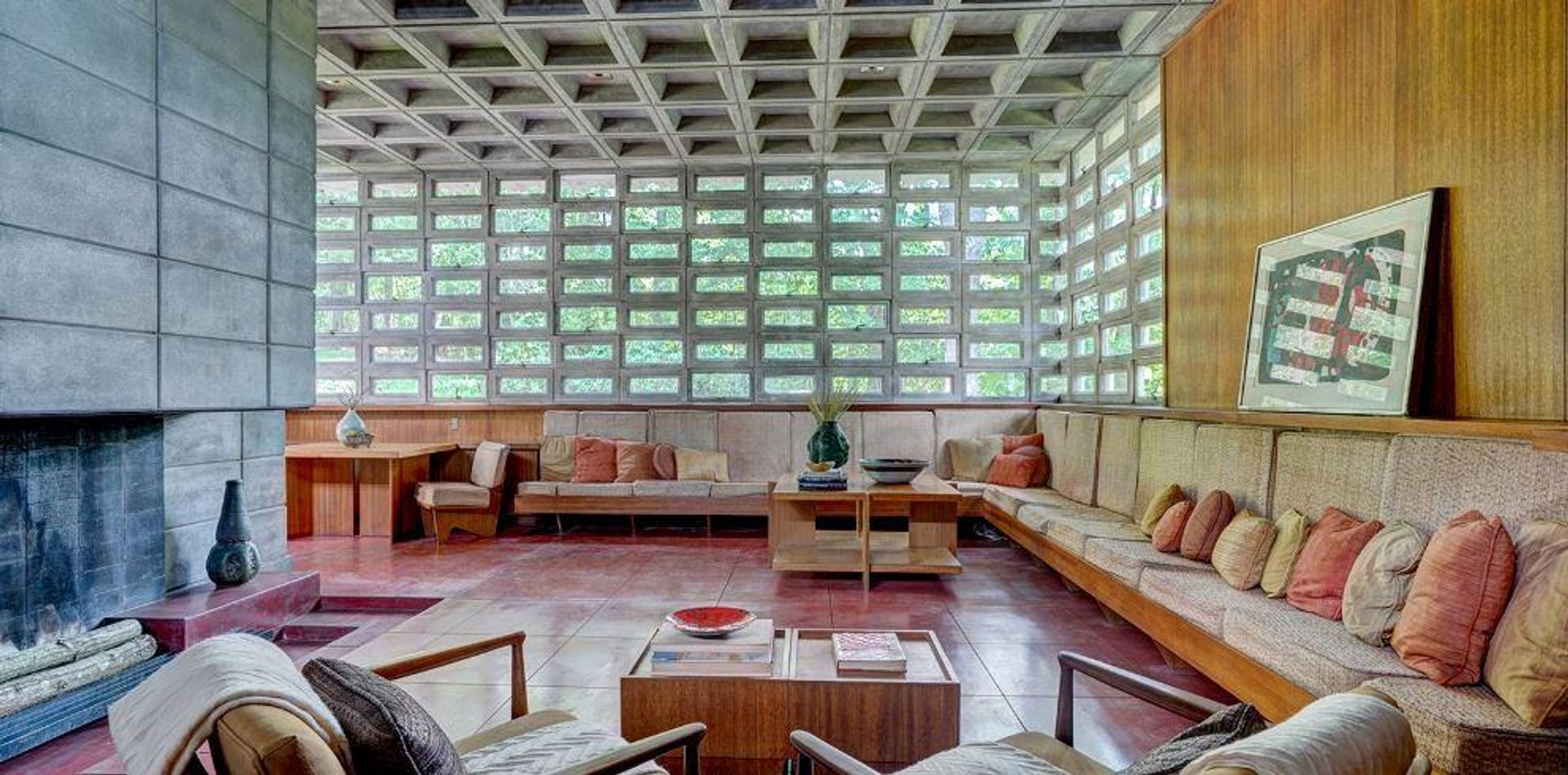

Like other Usonian Automatic houses, the two-bedroom, 1,400-sq.-ft home was designed by Wright with a gridlike masonry building system of stacked, individually cast rectangular concrete blocks. In its dramatic living room, 350 windows framed by concrete allow light to pour in, reflecting the architect’s philosophy of clean Modern design for the middle class.

The living room in the Kalil House, with the original furnishings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright Courtesy of Paula Martin Group

Chong says that the home, with its interior lined with mahogany, is in “exceptionally” good shape. “All of the original furniture [designed by Wright] is there, which is a great rarity,” he adds.

The museum director says that the impending sale had posed the risk that a new owner would enlarge the historic house or rip out the kitchen or bathrooms. Instead, the house will be preserved and opened for guided tours, like the other Wright home on the same street that the Currier also owns. Dr Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman left their house, built in 1951 with brick, a concrete floor mat and large windows in a “classic Usonian” style, to the museum in 1988 along with an operating endowment that finances its maintenance.

The museum says that Dr Toufic and Mildred Kalil were following in the footsteps of the Zimmermans, their friends and neighbours, when they commissioned the house from Wright in 1954. “Mrs Kalil is the one who wrote to Wright, saying that she was a great admirer and that they wanted to commission their own ‘functional home’,” Chong says. The couple travelled to New York City to visit Wright when he was working on the design and construction of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum there, he adds.

The 1951 home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman in the classic Usonian style Currier Museum of Art

Wright dubbed the style for the Kalil home Usonian Automatic because he believed that the owner might easily participate in construction by laying or even making the rectangular concrete blocks. In practice, the process was highly difficult, Chong says, and the Kalils relied on a contractor.

The house consists of two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a kitchen and the L-shaped living room with a dining area. It still has its original stove and oven, and Chong hopes to replace the current refrigerator and dishwasher with appliances that are truer to the room’s original style. “Sometimes these things just turn up,” he says.

Chong plans to start raising funds for an endowment for the Kalil House—“That’s a problem we will solve,” he says—and anticipates that tours could begin next April. “We will continue to make adjustments, but it’s worth revealing now as a work in progress,” he says. “We’re 90% of the way there.”

Among other visits, he wants to arrange special tours for museumgoers in the Currier Museum’s social programmes for people with Alzheimer’s, families afflicted by the opioid crisis, and war veterans. “We want to provide a rich, immersive experience of the house,” he says. “It will be a setting for discussion and conversation.”

The mahogany-lined and concrete-grid interior of the Kalil House Courtesy of Currier Museum of Art