“This was definitely a life-changing project in many ways,” says Julián Zugazagoitia, the director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, about the restoration of Queen Nefertari’s tomb in Egypt. Zugazagoitia worked on it in the early 1990s as a consultant with the Getty Conservation Institute, which gave the young art historian his first major curatorial experience.

“I very quickly discovered that I was not going to be a conservator myself,” Zugazagoitia says. He realised his career would follow “the path of exhibitions and communicating experiences”. A new survey Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt at the Nelson-Atkins is a return for the director not just to the objects and artefacts connected with the Egyptian queen—fondly known by her spouse, Ramesses II, as the One for Whom the Sun Shines—but also to some of his earliest considerations around exhibition-making and how audiences can experience art and history.

Built around 1250BC, Nefertari’s tomb was excavated in 1904 by the Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli who was the director of Museo Egizio in Turin (from where the exhibition draws its 230 artefacts). The burial chamber had long before been looted of artefacts by tomb raiders, who left behind just bits and pieces: fragments of pink granite from Nefertari’s sarcophagus, some small figurines and amulets, a pair of woven sandals (US women’s size nine) and a pair of mummified knees, all of which will be in the show.

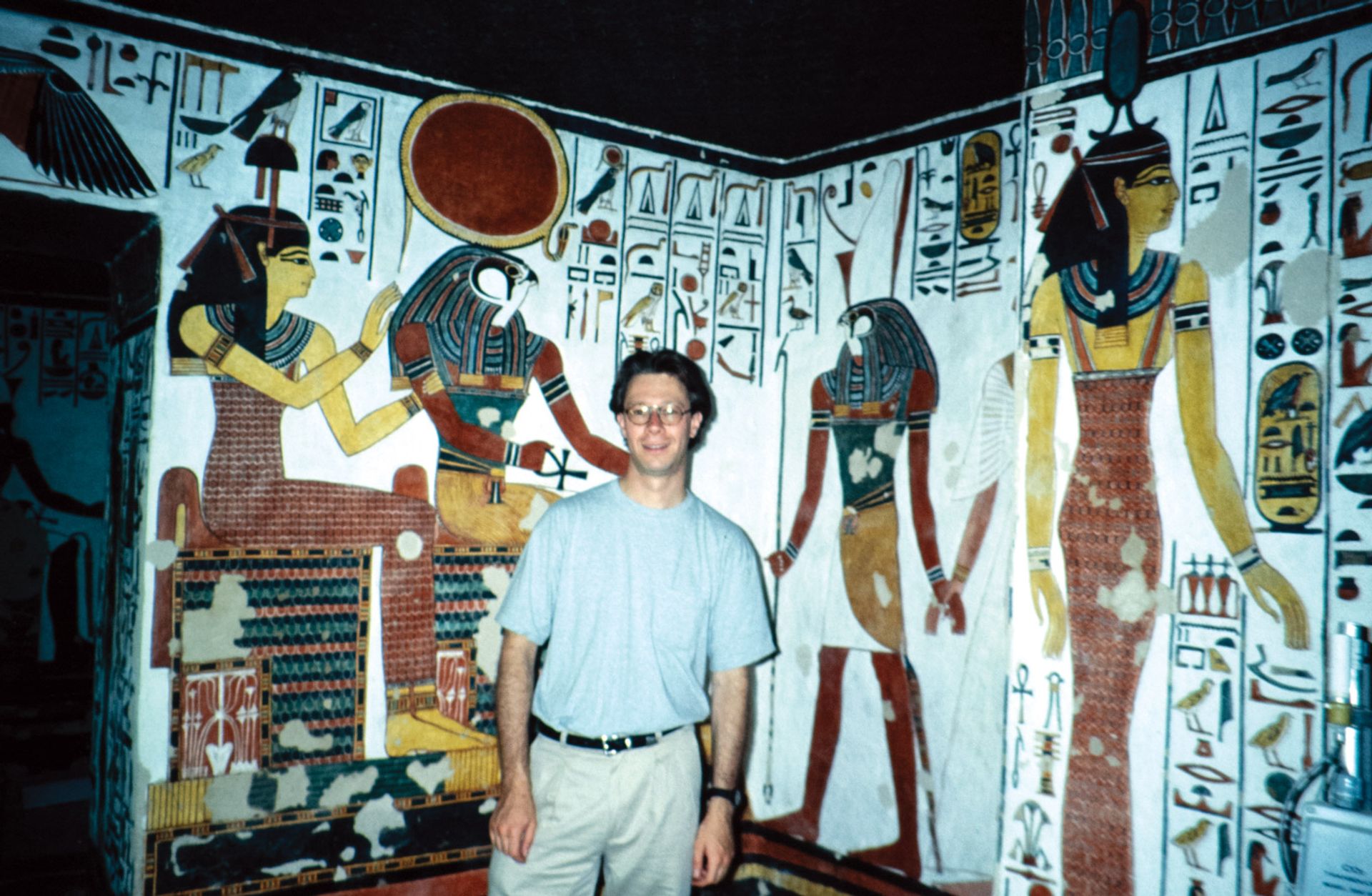

Julián Zugazagoitia as a conservator in 1993 Courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Museum

Although Schiaparelli found the tomb empty, he “nevertheless rejoiced in the discovery”, he later wrote, “since apart from being the tomb of one of the most famous Egyptian queens, it was also of a singular beauty”. Its vividly painted low-relief walls depicting Nefertari’s journey through the afterlife look as if they were painted yesterday rather than millennia ago. “That is one of the reasons it’s called the Sistine Chapel of Egypt, because it is definitely one of the best preserved,” Zugazagoitia says.

The tomb was closed to the public in 1950. After decades of visits to the site, and partly due to humidity introduced into the chamber by visitors’ breath, the mural plaster had begun to detach from the stone walls. A team led by the husband and wife conservators Laura and Paolo Mora, funded by the Getty with the cooperation of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation, subsequently spent six years painstakingly reattaching and securing the murals.

As the tomb was being prepared for its reopening in the mid-1990s, Zugazagoitia was drawn to how restored but still delicate sites could be safely visited by the public. “Firstly, it was exploring how tourism moved around the Valley Kings of the Queens—how to preserve, or how to create ecosystems so that people would enter but not damage the tombs, or which tombs could be frequented,” Zugazagoitia explains. He compares the challenge to the cultural tourism-driven overcrowding faced by museums today. “The fact that there’s so many people trying to enjoy the experience starts to backfire, because then it’s no longer an experience that is enjoyable,” he says.

The size-nine sandals found in the mausoleum Courtesy of Nelson-Atkins Museum

One potential solution was a technology still in its infancy 30 years ago—virtual reality (VR). “We were exploring if a VR reconstitution of the tomb would allow visitors to have an experience in a neighbouring empty tomb with no decorations,” Zugazagoitia recalls. A VR tour of the tomb was eventually created a few years later, when Zugazagoitia organised the 1994 blockbuster Nefertari: Light of Egypt at the Palazzo Ruspoli in Rome. Funded by Enel, Italy’s national energy provider, the innovative project required “a whole room full of RAM”, Zugazagoitia says. Offering visitors a virtual tour was much easier for the exhibition at the Nelson-Atkins, as a highly accurate depiction of Pharaonic Egypt for the video game Assassin’s Creed: Origins had already been created by the developer Ubisoft.

On top of the technological advances, the way society has progressed has changed how Nefertari’s story is presented, Zugazagoitia says. “While we were very proud to feature a woman, and a very important woman, 25 years ago, it was a statement, but it was not as powerful as what you can read into it today,” he says. “I think there’s a more focused story to be told around Nefertari, and all the themes around her—about the role of women and their power—that makes her come alive much more vividly.” Perhaps for him more than most. “She is almost a relative now.”

• Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 15 November-29 March 2020. The show is organised by the Museo Egizio and StArt in collaboration with the Nelson-Atkins, Pointe-à-Callière and the National Geographic Society.