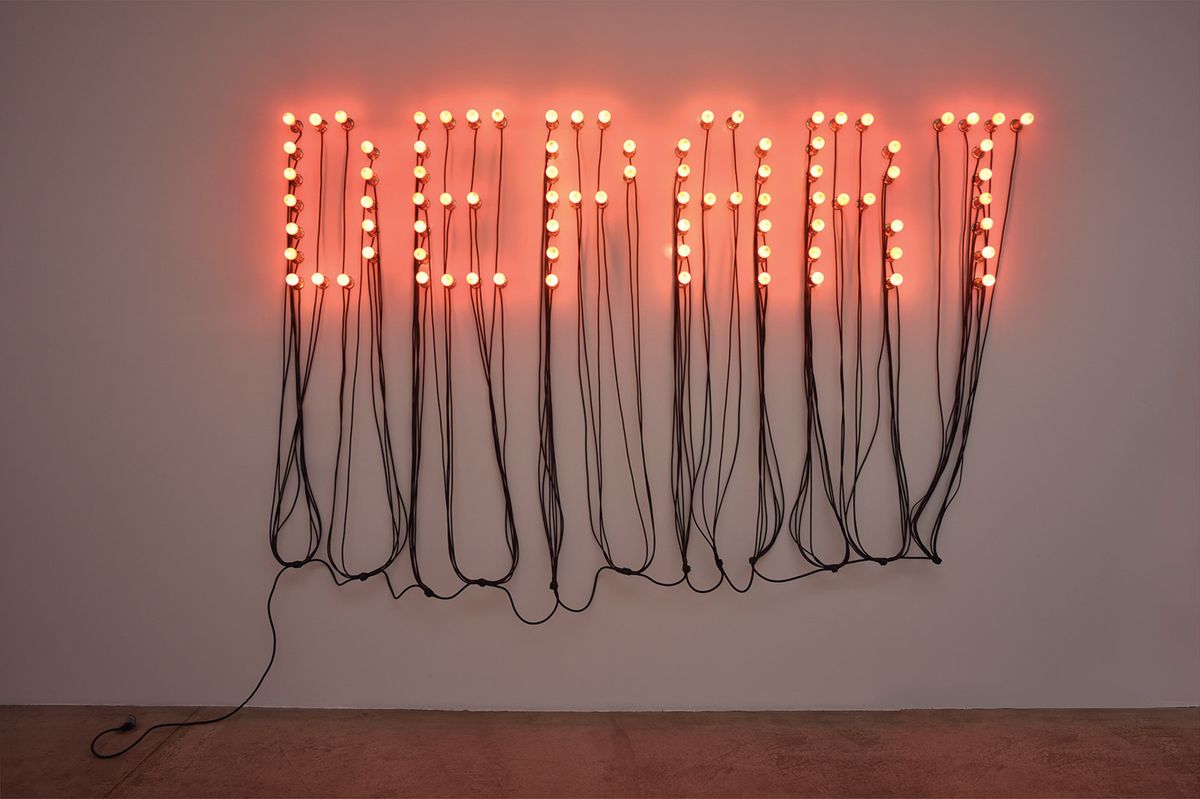

Christian Boltanski’s second retrospective at the Centre Pompidou is an ambitious undertaking. The museum’s director Bernard Blistène has, along with Boltanski, conceived the show as a labyrinth. Viewers will take an immersive journey, marked at the start and end of the exhibition by Boltanski’s light sculptures spelling out their titles: Départ and Arrivée (both 2015).

Until the mid-1980s, Boltanski took a playful, conceptual approach to a range of media including film, found objects and photography, exemplified in Saynètes Comiques (comic sketches, 1974), a sardonic and fictionalised response to his childhood. But the exhibition’s labyrinth —an artwork in itself—reflects Boltanski’s shift to more “enchanted works” in the mid-1980s, Blistène says. “It was the first time he considered illuminating his works with his own lights, without any exterior lights, and that’s the moment where he decided to build larger installations.” His approach changed, too. “The first works refer more to history, and what he does now is closer to mythology,” Blistène says.

Several of these transformative pieces will appear in the Pompidou show, including Théâtre d’ombres (1984-97), a danse macabre where tiny illuminated sculptures throw shadows against the walls. For his Monuments series, he reshot photographs of children in class photos in Dijon and Hulst where he went to school, as well as, hauntingly, of a group of Jewish schoolchildren in Vienna in 1937—a rare explicit reference to the Holocaust. In works like Reliquaire (1990), these images were accompanied by tin boxes, at once evoking keepsakes and urns.

Christian Boltanski's Animitas Chili (2014) © Photo: Francisco, Rios Anderson

Collective memory and loss continue to permeate his work, whether ambiguously in installations featuring piles of discarded clothing, or more specifically in the video installation Animitas Chili (2014). In the latter work, a series of bells gently tinkle in the breeze in Chile’s Atacama Desert, a site where people were murdered by the Pinochet regime (“animitas” is the name for roadside shrines in Chile).

Film and performance have been part of Boltanski’s work from the start and Blistène sees in his output today an “amazing alliance between theatre and cinema”. Nowhere is this clearer than in Boltanski’s dramatic three-screen video installation Misterios (2017), shot in Patagonia where whales gather off the coast. Here we see Boltanski’s menacing sculptures manipulating the air to evoke whale sounds, calling out to the pods in the open ocean, while another screen displays a whale’s skeleton. Blistène wants to acquire this work, the beast at the end of his and Boltanski’s labyrinth, for the Pompidou collection.

• Christian Boltanski: Faire Son Temps, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 13 November-16 March 2020