Motivated by today’s atmosphere of exacerbated nationalism in Southern Asia, 11 artists will present works that question borders and address issues of displacement and migration in Homelands: Art from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.

The exhibition of South Asian artists was commissioned at the beginning of the European migrant crisis in 2015 and opens “at a time when Britain is being radically reconceived”, says its curator Devika Singh. “It seems that the exclusionary lines drawn in South Asia are not that different from those being drawn here in the UK and Europe,” Singh adds.

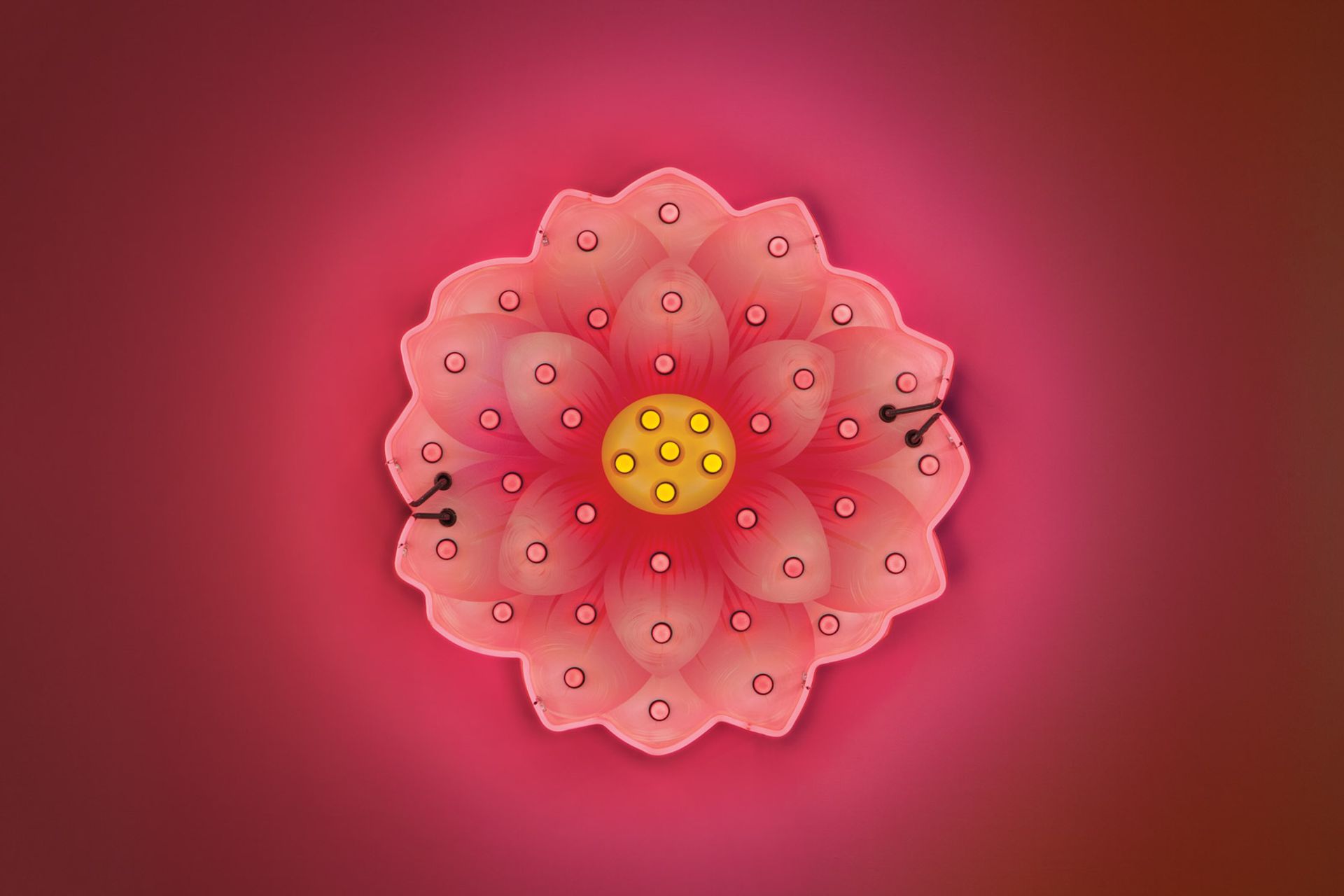

Some of the works in the show play with the logic behind national identity, such as Iftikhar and Elizabeth Dadi’s large neon sculptures based on the national flowers of Bangladesh, India and Afghanistan. These pieces broach the strangeness of exclusive claims to species of flora that grow on either side of a border line. Others works, such as a series of new abstract paintings by Desmond Lazaro, are inspired by the intimate histories bound up in great displacements. Lazaro produced the paintings during a residency in Cambridge, basing them on individual stories and objects from immigrants who have moved to the area.

Padma, Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi (2014) Courtesy the artists

The show also features attempts at fostering international co-operation through art, such as a 2002 poster by Shilpa Gupta, first conceived during an artistic exchange programme between India and Pakistan. The two neighbouring countries’ longstanding tensions escalated in February this year following a suicide bombing at the national border by a Pakistan-based terrorist group that provoked deadly airstrikes on both sides.

At the centre of this historic conflict between the two nuclear-armed nations lies Kashmir, the heavily militarised Himalayan region in which both countries claim territory. Addressing this issue, Sohrab Hura’s Snow, an ongoing series started in 2014, depicts the progression of winter in the Kashmir valley using subtle motifs such as eyes to refer to the blinding of civilians by the police using pellet guns.

“I am keen to state that mine is not a Kashmiri voice, it is an Indian’s—an important distinction to make especially in light of recent events,” says Hura, referring to the ruling made by the Indian government in August to strip the state of Kashmir of its semi-autonomy. Imposed a day before thousands of troops descended into the region and effected a state-wide lockdown on movement and communication, now in its fourth month, the ruling has drawn widespread criticism with vocal opposition from Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan.

As tensions remain high and political leaders continue to exchange hostile words, it is doubtful a show of this nature could take place in either country today. “While collaborative shows like this do exist, they remain infrequent and are faced with many logistical complications,” Singh says. “Most importantly, it is still very difficult for artists to travel to and from either country.”

Staging this show in the UK not only affords Singh the logistical ease of intra-national collaboration but also provides Homelands with an important context for viewers to contemplate. Although the exhibition’s works were not necessarily created with a British audience in mind, Singh notes that “British colonial history and the role of British power at the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan is irrefutable, and its lasting impact is an important dimension to consider.”

This history is central to another work by Shilpa Gupta that resembles a railway station signage board. The numbers it shows represent not only train timings but also the death toll of the mass killings of train passengers attempting to resettle upon Partition. The splitting apart of ancient cultures overnight is also the subject of a series of photogravures by Seher Shah, which shows images of 2nd century AD. Buddhist sculptures originally found at the former border of Pakistan, Afghanistan and India, whose ownership is now contested between the nations.

Singh hopes that Homelands will, “provide a challenge to present-day forms of narrow-minded nationalisms”. By observing the common histories that lie on either side of borders this show should remind viewers of the largely artificial and arbitrary nature of the lines that divide people today.

The exhibition is supported by the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, among others.

• Homelands: Art from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, 12 November- 2 February 2020