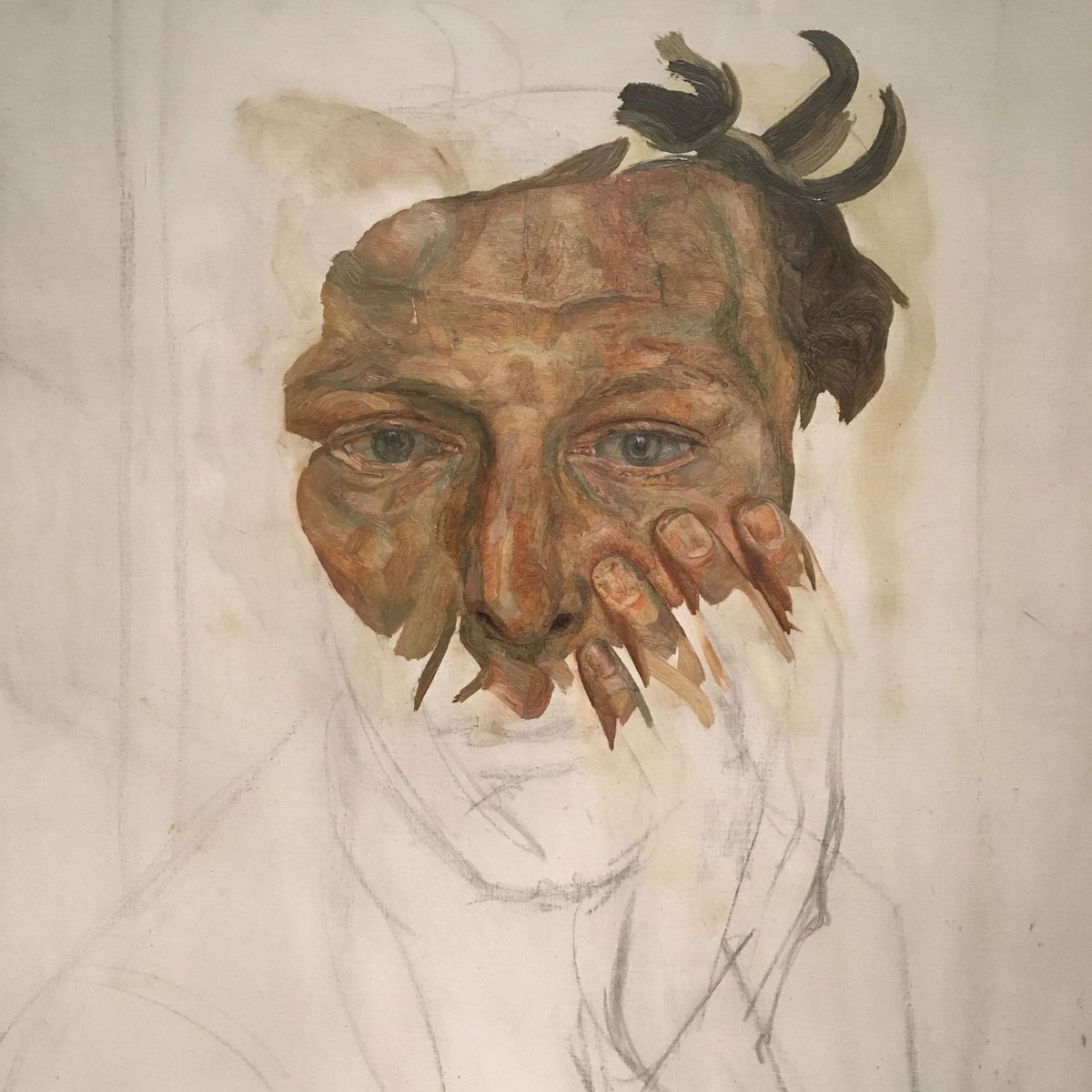

They sure do pack a punch. The stunning show Lucian Freud: the Self-portraits (until 26 January 2020; tickets £18, concessions available) at the Royal Academy of Arts runs from Freud’s early precocious drawings he did as a teenager to late paintings where the impasto is perfect for his sagging flesh. Freud usually began his portraits from the nose, working his way outwards, as can be seen in several examples including Self-portrait (around 1956, picture above) and the exquisite oil on copper miniature Self-portrait (1952). The latter work —painted while Freud was aboard a banana boat travelling to stay with Ian Fleming and his wife Anna at their Goldeneye villa in Jamaica— is “one of the most remarkable works in the exhibition”, says the co-curator Jasper Sharp. Another highlight is Self-portrait with a Black Eye (1978), which he painted shortly after getting into an altercation with a taxi driver, something that he “found thrilling”, Sharp says. Freud is surrounded by wild stories of gambling, fistfights, hanging out with gangsters, and speculation on the number of children he is said to have fathered. But there is also a real sense of pragmatism in this show, of plugging away at his craft while movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art came and went. “He was deeply unfashionable for years and years,” Sharp says, but “he persisted”. The persistence paid off—this is a knockout show.

Around 150 Egyptian artefacts from King Tut’s tomb, 60 of which are being shown outside Egypt for the first time, go on show this weekend in Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh at the Saatchi Gallery (2 November-3 May; tickets from £28.50, concessions available) in the third leg of a multi-city tour that is due to run until 2022. After a short video introduction, visitors pass large-scale images of the colourful wall paintings from the Boy King’s tomb, complete with their mysterious brown spots, before entering a series of dimly lit galleries filled with everything Tutankhamun needed in the afterlife. Visitors can expect to see golden objects as far as the eye can see, from decorative pectorals to statuettes of both the pharaoh and various gods, including a lovely one of Ptah, the god responsible for, among other things, opening the mouth of the deceased. For those who delight in more unusual objects, be on the lookout for a pair of the pharaoh’s golden flip flops or the individual golden coverings for his fingers and toes. And if you feel the need to bring some of the Tut magic home with you, the giftshop offers a healthy mix of replicas and Tut tat, including rubber duckies dressed as mummies.

In 1981, on the streets of Rio de Janeiro, the artist Anna Maria Maiolino negotiated a path barefoot across a pavement littered with chicken eggs. The performative piece, Entrevidas (between lives), reflected the precarious new political order in Brazil following the decline of the country’s omnipresent military dictatorship. Photographs of the work are included in the comprehensive survey Making Love Revolutionary (until 12 January 2020; £12.95, concessions available) at the Whitechapel Gallery, spanning six decades of Maiolino’s revolutionary practice. Other startling images depicting life under the dictatorship include É o que sobra (what is left over, 1974), which shows Naples-born Maiolino threatening to slice her tongue with a pair of scissors. The artist’s innovations in a variety of media are notable, from abstract fabrications moulded out of folds of paper—such as Desenho Objeto (drawing object, 1974-76)—to arresting photographs, especially By a Thread (1976), which shows a single strand hanging in the mouths of Maiolino, her mother and daughter.