At the heart of New York’s Performa, the biannual festival dedicated to performance art, is what the founder RoseLee Goldberg calls a “radical urbanism”. Spanning both public and private sites of varying size and visibility, the event has always used the city’s architecture in innovatively democratic ways. “It’s about not giving into the limits of real estate,” Goldberg says. It is an admirable quest in a perpetually and aggressively developing metropolis beset by wealth disparity like New York. A notion of urban radicality underpins the eighth edition of Performa as it launches more than 20 newly commissioned works across multiple locations.

The 2019 iteration is also commemorating the centenary of the Bauhaus—itself a utopian artists’ project intended to re-think architecture and social spaces in a fractured country in need of innovation. Founded in Germany after the First World War by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus was the first art school to squarely place theatre and performance within the context of visual art. In tribute, the US photographer and classically trained dancer Kia LaBeija presents her first live theatrical work for Performa, drawing from the third act of Triadic Ballet (1922), a pivotal early Bauhaus ballet created by Oskar Schlemmer. Often called the “black act” due to its themes of fantasy and mysticism, LaBeija re-envisions the absurdist dance using a range of movements from classical forms of vogueing to contemporary ballet.

It’s immediate—you can’t just walk by it like a painting on a wall

At the heart of Triadic Ballet are geometric costumes—in LaBeija’s interpretation these are designed by the stylist Kyle Luu, known for her work with musicians like Solange and Travis Scott—that turn the performers’ bodies into architectural entities that struggle to move autonomously and instead must interact with each other in new and creative ways. It points to a need for community, according to the artist, who says “we are all on separate but parallel journeys” that require us to look outside of ourselves to find wholeness.

Indeed, Goldberg says that a key strength of performance art is that it provides a rich way to visually narrate the relationship between identity politics and the collective environment. A sense of fantastical social reform comes through in numerous other projects that will be on view throughout the biennial, often through the language of architecture but also through myth—both of which serve as fundamental blocks for restructuring social paradigms.

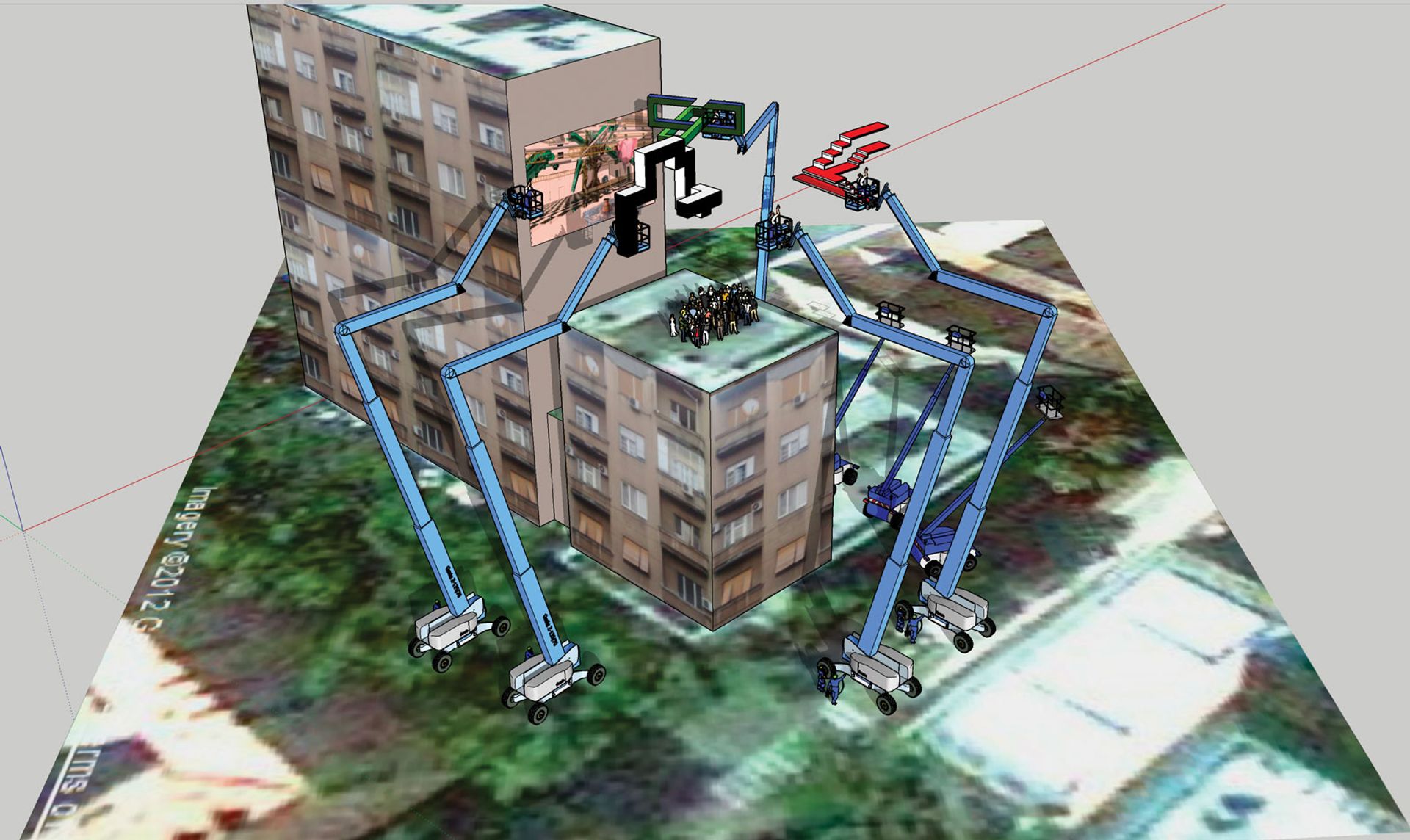

Samson Young's sketch for his Performa 19 commission © the artist

The Hong Kong-based artist and composer Samson Young will debut his first experimental musical, The Immortals, which is based on a centuries-old Chinese fairy tale. The work will feature eight deities on a stage where a number of cherry-picker cranes will slowly rotate and shift the set throughout the performance. Young is recasting the deities as artists who are able to see or hear things that others cannot, aiming to create a modern-day allegory of cultural production in late capitalist society.

Meanwhile, the London-based artist Paul Maheke and the musician Nkisi have created a live performance using light, sound and movement that will explore how diasporic community identity is reshaped—or lost—within a foreign environment, drawing inspiration from the folklore and ancestral knowledge detailed in the 1991 book African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life and Living.

By making history present, performance can often help rewrite the future. “It’s a confrontation, it’s immediate—you can’t just walk by it like a painting on a wall,” Goldberg says. “That’s what the Bauhaus understood about it as an art form: this need for physical play and movement as a mechanism for understanding social dynamics and, more broadly, the nature of being.”

Major funders of Performa 19 include the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and Toby Devan Lewis.

• Performa 19, various venues, New York, 1-24 November