Florine Stettheimer will make way for Alfred Stieglitz. Harry Callahan will yield to Gordon Parks. And Mrinalini Mukherjee will move out for Moustapha Dimé.

Even as the expanded Museum of Modern Art in New York showed off its rearranged permanent collection this month—presenting a more global and inclusive story of Modernism—curators were deep into deciding what would go on view next spring. MoMA has promised to rotate about a third of the works on all three collection floors every six months, in contrast with the traditional museum practice of leaving collection displays largely untouched for years.

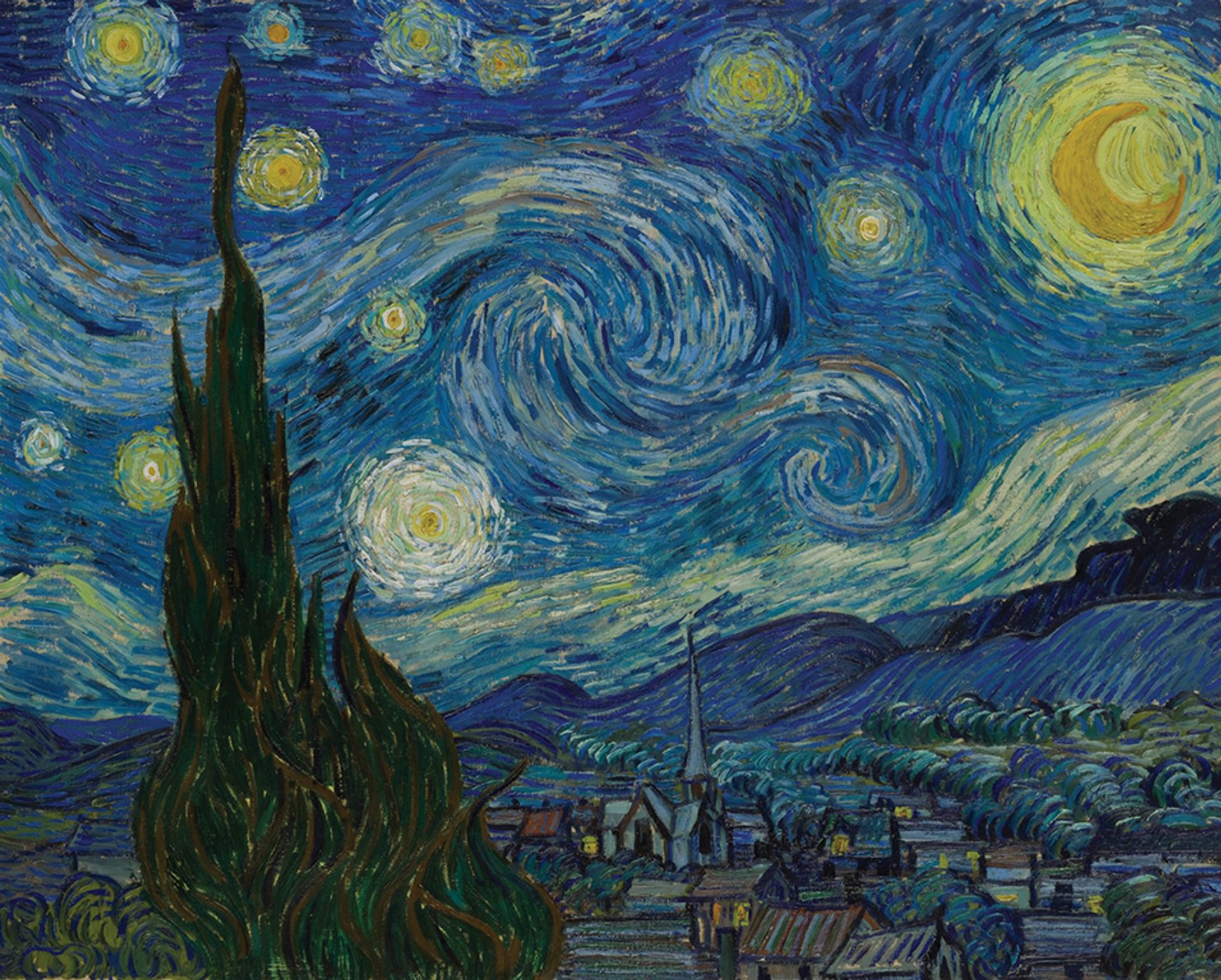

That means that about 735 of the 2,200 works will be plucked from their places next April, and gradually replaced, usually in groups, by 1 May. It is an enormous undertaking, considering that curators can draw on some 200,000 items in MoMA’s collection, with only about 15, such as Van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), expected to be always on view, according to Ann Temkin, chief curator of paintings and sculpture.

Van Gogh's The Starry Night (1889) will remain on view at the Museum of Modern Art Museum of Modern Art

The task is further complicated because not all of MoMA’s best-known works can be shown at once. “The last thing we wanted to do was create an A team for the first installation and then go on to the B team,” Temkin says.

MoMA owns three combines by Robert Rauschenberg, for example, but only Canyon (1959) is on view. Either Bed (1955) or Rebus (1955) is likely to come back next spring, but not, like Canyon, in a gallery called Stamp, Scavenge, Crush—it will probably go instead in the Glue, Gather and Tear gallery, which will showcase artists who use found materials for their works, says Christophe Cherix, chief curator of prints and drawings, who supervises the fourth-floor galleries.

Fortunately, MoMA’s decision to tell “multiple histories” of Modernism, using these themed galleries with titles, will ease the rotations. Many galleries can turn over completely and shift in theme without disrupting the museum’s chronological spine.

On the fifth floor, what is now Florine Stettheimer and Company will be dismantled for Alfred Stieglitz and his Circle. There, alongside Stieglitz’s Georgia O’Keeffe—Hands (1919), will hang O’Keeffe’s Evening Star No. III (1917) and works by artists Stieglitz championed, including Arthur Dove and Max Weber.

And the Abstraction and Utopia gallery, now displaying two works by Mondrian, will become entirely devoted to the Dutch painter. It will trace his evolution from figuration toward abstraction to Neoplasticism, when his palette shrank to red, yellow, blue, black and white. His famed Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-43), now displayed in a temporary show of mostly Latin American abstract works, will return to the collection galleries, as will Composition in Red, Blue, and Yellow (1937-42), which is not on view.

Gordon Parks will take over a fourth-floor gallery now called Abstract Lens, which showcases photographs made by Callahan and others who experimented with abstraction and Expressionism. Gordon Parks and the Atmosphere of Crime will offer a grittier selection of photographs, capturing the intersection of crime and race, anchored by those that Parks took for Life magazine.

And on the second floor, a gallery titled Transfigurations, which shows a hemp sculpture by Mukherjee along with other works about the female image, will become one tentatively titled World Knowledge. There, works by artists such as the Senegalese sculptor Dimé and David Hammons will examine how artists have dealt with globalisation and geopolitical turmoil.

Mrinalini Mukherjee's Yakshi (1984) will be rotated out of a gallery titled Transfigurations at the Museum of Modern Art Museum of Modern Art

Elsewhere, galleries will retain their themes but display different artists. Four Photographers, Four Places will become Five Photographers, Five Places, displaying artists who used handheld portable cameras, such as Barbara Brändli in Caracas and Richard Misrach in Berkeley.

For practical reasons, MoMA decided to designate which galleries will change by their location: this time, only spaces in the new Geffen wing will switch out. As a result, the earliest galleries in the chronology on each floor will largely remain the same for now, with only works on paper rotating for preservation reasons. On the fifth floor, that means the galleries displaying The Starry Night and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, for example, will not be touched.

But some heavyweights may move, such as Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans. Cherix says curators are debating where to put it and whether to show the 32 canvases that make up the work in a line, like cans on a shelf, as it was when first exhibited in 1962, and not as a grid, as it is currently displayed.

Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans (1962) might be reinstalled in a different way at the Museum of Modern Art, with its 32 panels lined up in one row © 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation/Artists Rights Society, New York

The rotation plan is not without costs. Early on, some curators wondered whether special exhibitions might suffer as a result of the extra workload. Under the new philosophy of putting the collection at the centre of everything, Temkin says, “We will do more special shows from our own collection.”