This article was featured in our Art Market Eye newsletter. For monthly commentary, insights and analysis from our art market experts straight to your inbox, sign up here

Some two years ago, fractional investment in art was the hottest topic around. On panels in art market centres in New York, Basel or London, speakers enthused about how selling shares in works of art could transform and democratise the art market.

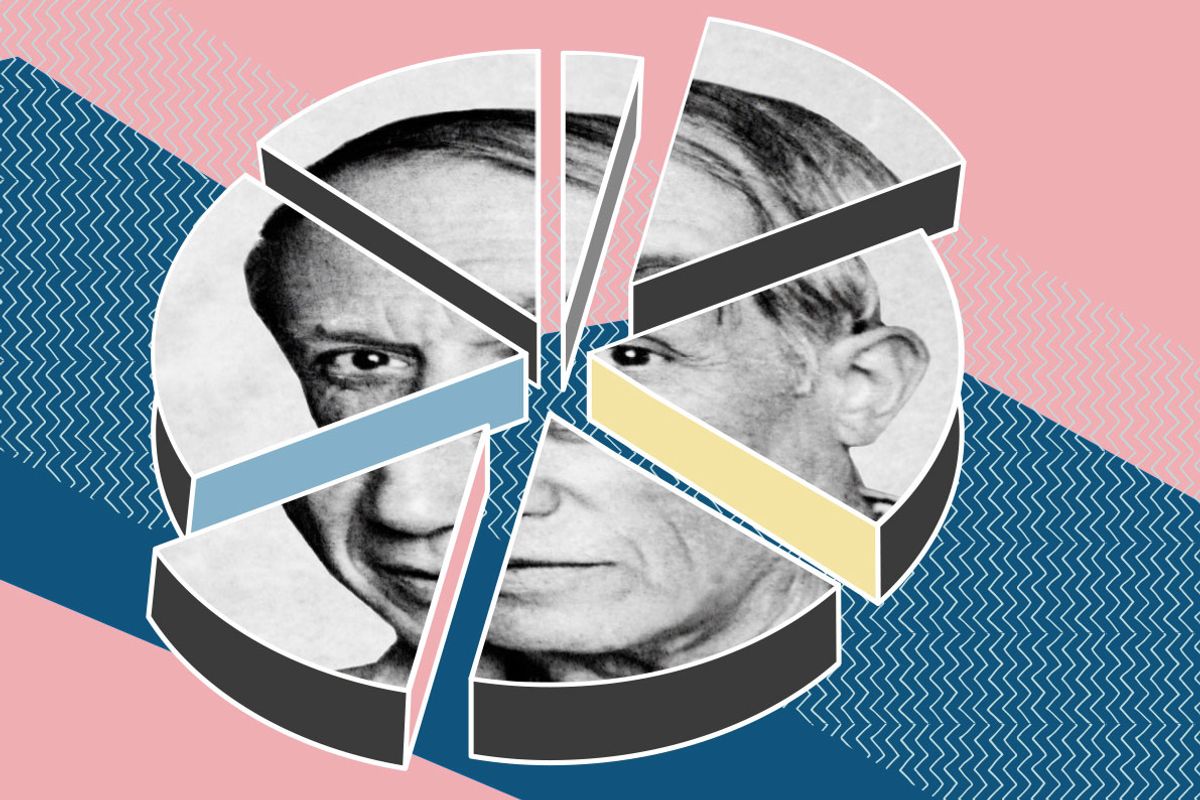

They said that even the small investor could own a share in, say, a multi-million-dollar Picasso. Further, the idea was that the shares could be traded, as derivatives, on an exchange, without the underlying asset being sold. The transactions would be recorded on a blockchain, another red-hot topic at the time.

Companies such as Feral Horses, Maecenas, Masterworks or Look Lateral were founded, later joined by start-ups such as ArtSquare (“the new art market, for everyone”) Malevich (“we make art accessible”) or Artopolie (“turns art into fractional shares”).

So where are we now?

One of the best funded of these firms is Maecenas, with more than $15m in investment. In 2018 it sold 31.5% of a tokenised work, Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980), for $1.7m, becoming the first company to do this. However, the amount fell well short of the 49% ownership that was on offer.

Payment was in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin or Ethereum, or Maecenas’s own ART. Cryptocurrencies have been volatile, and Maecenas is now rolling out a new “tokenisation vehicle”, with existing tokens migrating to the new structure. It is also operating an “airdrop”, giving away small quantities of tokens. According to its co-founder and chief executive Marcelo García Casil, the new token will “open up the market to non-accredited investors”. Asked about the departure of Maecenas’s head of marketing, Marc Garriga, Casil says: “Like every other company, we have staff changes.”

Meanwhile, what about the Warhol? It was sold by a London gallery, Dadiani Fine Art (in partnership with Maecenas), which has now closed. Eleesa Dadiani, the gallery founder, says she is still working as an art dealer, but has not yet decided on a new physical space. She says the Warhol is in storage in Switzerland and “we are set to tokenise the remaining 68.5%”.

In 2018 Maecenas sold 31.5% of a tokenised work, Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980), for $1.7m © 2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; Inc/Artists Right Society (ARS); New York and DACS; London

Other start-ups in the same space have also had to make changes: some exchanges, often promised for 2019, have been pushed back to 2020, and Initial Coin Offerings (ICO) have mainly been superseded by Security Token Offerings, which are backed by real assets such as commodities or equities. For Maecenas, Casil says that Atex-exchange, which would allow holders to trade tokens, “should happen soon, within weeks”.

Opinions are divided as to the future of this field. For Frédéric de Senarclens, the founder of ArtMarketGuru, there is the difficulty of creating liquidity in this field and the lack of a big enough client base. “The desire for fractional investment in art is not clear,” he says, noting that “most of these ventures have been created by people with no background in art”.

The 2019 Deloitte Art and Finance report notes that only 19% of collectors and art professionals said they were interested in fractional ownership, although younger and newer buyers were far more interested than older and more established ones. For Deloitte’s global art and finance director Adriano Picinati di Torcello: “The future of fractional ownership could be bright, but a certain number of challenges need to be overcome to make it mainstream.”

There is no doubt that interest in all forms of investment in art is currently high, boosted by the immense prices realised for a few works. However, for me, fractional ownership poses multiple problems. The high prices are for a tiny fraction of works, and to imagine that all art is a good investment is simply wrong. The lack of homogeneity between different artworks is another obstacle and a Warhol can be worth ten, or 100, depending on a number of factors: art is not a fungible asset like gold or stocks. The founders’ lack of expertise in the art world must be a problem here. The promised exchanges have yet to materialise, and the use of tokens and cryptocurrencies poses problems for oversight, volatility and of possible wrong-doing. And finally, it is not clear, as De Senarclens says, that there is really much of an appetite for what is a very speculative field.

• This article was commissioned for Art Market Eye, a market-focused monthly newsletter produced by The Art Newspaper. Sign up here to receive it straight to your inbox.