Casting a spotlight on the fraught nature of antiquities acquisitions, the exhibition Rayyane Tabet/Alien Property at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until 18 January 2021) tells the intertwined story of four Neolithic reliefs excavated in Tell Halaf, an archaeological site in present-day Syria, and an ancestor of the Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet. The show aims to “encourage conversations around acquisitions, provenance, and who benefits, suffers or is allowed to own antiquities”, says Kim Benzel, the museum’s curator in charge of ancient Near Eastern art, who teamed with Clare Davies, the assistant curator of Modern and contemporary art, to organise the show.

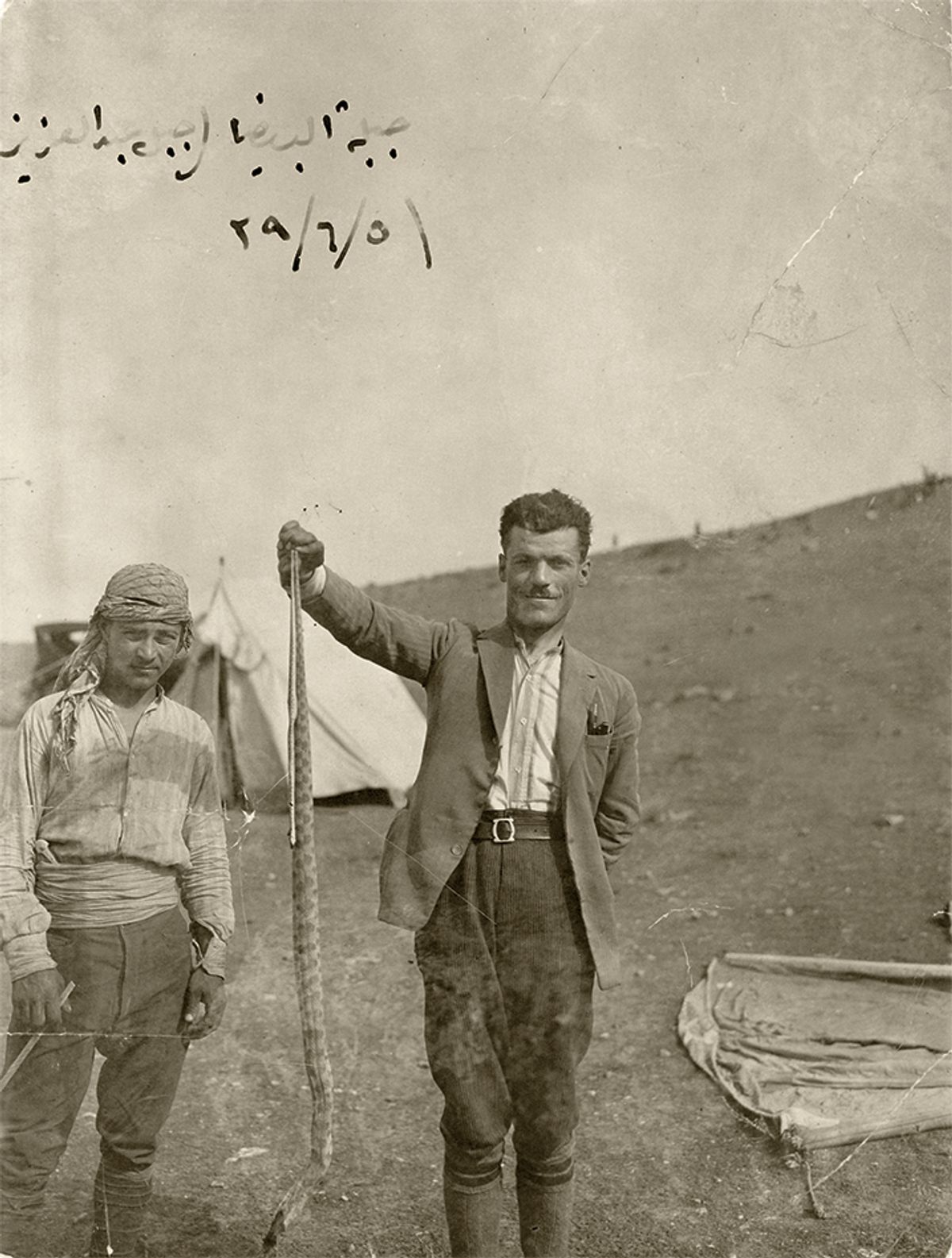

Tabet first approached the museum in 2016 to request permission to produce charcoal rubbings of four ninth-century BC stone reliefs from Tell Halaf. His goal was to conceptually “resuscitate” an extant frieze from the site that was excavated in the early 20th century by the German archaeologist Baron Max von Oppenheim. Tabet was inspired by his great-grandfather, Faek Borkhoche, who worked incognito as a translator alongside von Oppenheim in Tell Halaf while serving as an informer for the French government. Borkhoche suspected Oppenheim of using the dig as a cover-up for mapmaking activity in areas under French and British rule.

“There were always myths about my great-grandfather, von Oppenheim and this excavation,” Tabet says. “There was a photograph of Oppenheim—who looked nothing like us—hanging on the wall of my grandparent’s house, and there was an archaeological book written in German, a language none of us spoke. I was intrigued enough by the story to pursue it, and eventually learned that artefacts from the excavation had ended up in museums around the world, including the Met. At that point, what started as a personal project became something much bigger.”

Starting in 1911, von Oppenheim oversaw the excavation of around 200 reliefs from the ancient site. Borkhoche’s spy mission ended with no evidence against the archaeologist, and he returned to Beirut after six months with some mementos from the dig, including photographs and a copy of von Oppenheim’s book about the expedition, Der Tell Halaf. Borkhoche’s copy of the book is exhibited along with the museum’s own version, in which von Oppenheim has inscribed a dedication to Herbert Winlock, who was the director of the Met when von Oppenheim visited the museum in 1932.

Around 1931-32, von Oppenheim brought eight fragmented reliefs from Tell Halaf to the US but placed the artefacts in storage after he failed to sell them. In 1943, US authorities seized the reliefs under the Alien Property Custodian, a mandate launched during the First World War and reactivated during the Second World War stating that the US government had the power to search, investigate and seize the belongings of enemies, which included German nationals such as von Oppenheim.

The reliefs were offered at public auction that same year; the Met bought all eight for $4,000 and immediately sold four of them to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The exhibition displays the original acquisition documents, which marks a “big gesture and shift for the institution, which usually never discloses these types of documents”, Tabet says.

One of the four reliefs from Tell Halaf in the Met's collection depicts a seated figure holding a lotus flower The Metropolitan Museum of Art

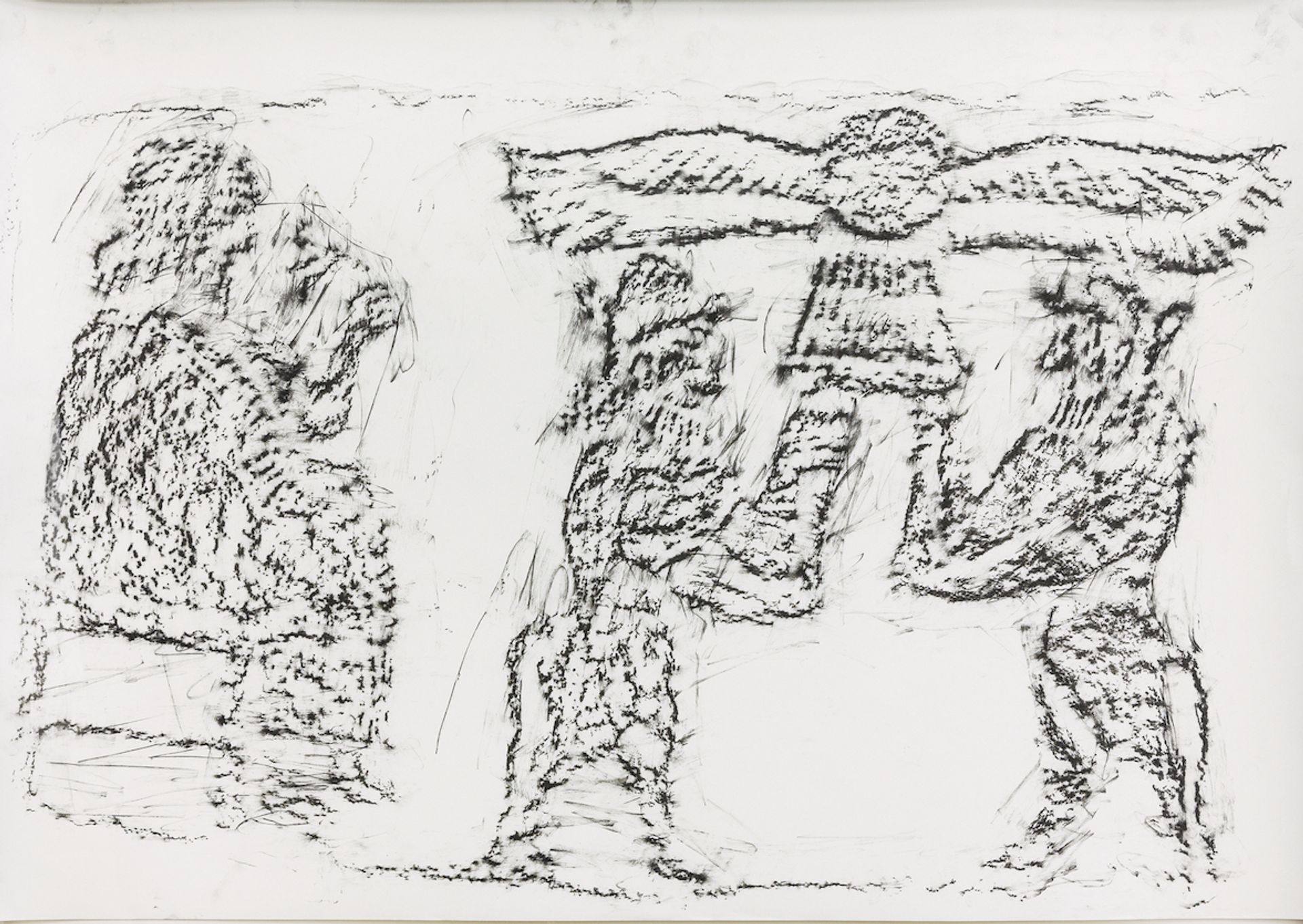

The rubbings Tabet made from the reliefs in the Met are displayed in the exhibition with those he made from fragments from Tell Halaf held in the Walters Museum and at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. (There are 32 rubbings altogether.) Other existing fragments from the site, which are not included in the show, can be found in the National Museum of Aleppo and the British Museum; still others are missing or were destroyed during the Second World War.

“This mirror between our stories—between the ancient site, the museum and these personal stories I grew up with—can maybe provide a platform to confront things like war and colonialism as it relates to the acquisition of antiquities,” Tabet says. “The reliefs, shown in this context, can be an opportunity for the institution to lead the conversation, rather than follow it whenever there’s a scandal.”

A rubbing by Rayanne Tabet of the aforementioned relief The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A 20m-long rug made by the Bedouin tribes in Tell Halaf, which Borkhoche had requested should be cut and dispersed among his descendants, forms the work Genealogy (2017) in the exhibition. The family heirloom has been cut into 23 pieces across five generations, of which five pieces appear in the work, which amplifies “the idea of the fragmentation and dispersal of ancient objects”, Tabet says. The work also “allows a personal and private artefact to enter these galleries and confront artefacts that, for the most part, have been dealt with scientifically and analytically”.

The show also displays a restored seated figure that was destroyed during a 1943 Allied bombing attack that struck the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin, which von Oppenheim opened in 1930 with his own funds after pieces from his excavation were rejected for display in the Pergamon Museum. “Not one object shown in this exhibition is whole; these fragments are just one piece of the puzzle,” says Benzel. “We’re often stuck in a historical dead end, and maybe we can use these fragments as a step toward putting this spectacle in context.”

In a year-long series of programming around the show, on 30 October the artist will stage a performance in the gallery where he narrates the history of the reliefs, at times speaking about the artefacts and to the artefacts. The performance is “about embodiment”, says Tabet. “One of the tricks that institutions and encyclopedic museums are very good at doing is distancing you from the objects. The idea that I’m standing in these galleries telling these stories, as the person that I am, is already releasing these objects from those confines.”

- Rayyane Tabet/Alien Property at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (until 18 January 2021)