Who knew cardboard could be so contentious? A long-running lawsuit regarding damage to the cardboard frames on a triptych of Martin Kippenberger paintings has quietly come to a conclusion as a Los Angeles court rejected a nearly $100m bad faith claim against the insurance company XL Specialty.

The case was brought by the paintings’ owners, Stanley and Gail Hollander, in 2007. They sought more than $90m in damages in connection with a claim for alleged loss in value on the works Copa III, Copa IV and Copa IX (1986) after damage caused by a handling hiccup. After a three-week trial by jury and millions spent in legal fees, Gail Hollander (Stanley died in 2016) received just $19,500, their claim undone by a curious restoration of the paintings’ frames.

According to court transcripts seen by The Art Newspaper, the Hollanders purchased the works in 2004 from Gagosian in London for $289,000 ($96,333 each). They sought a fine art insurance policy from XL Specialty for the works in March 2005. Oliver Barker, Sotheby’s London senior director, was asked by the Hollanders for an appraisal; he advised a pre-sale estimate of $123,000 to $158,000 should they want to sell the works at auction and an open market estimate of $399,000 for insurance purposes.

Handle with care

The catalyst for the collectors’ legal action occurred shortly thereafter. In January 2006, a seemingly innocent art handler blunder led to the removal of the paintings’ frames when the works were shipped and installed in the collectors’ California home.

Kippenberger was an irreverent artist who wanted to “undo the definition of painting and its presentation”, says Peter Hastings Falk, the editor of the publication Discoveries in American Art and an expert witness in the trial, which concluded in May. The artist’s Copa series boasted corrugated cardboard frames that were mistaken as packing material and partially removed by the handler. “The cardboard frames were part of [Kippenberger’s] game,” Falk says, “you have to see them as integral to the piece.”

XL Specialty asserted its contractual right to try to restore the paintings when the Hollanders’ lawyers filed a claim, later seeking a total loss payout for the full policy amount of $399,000. The collectors and the insurance claim handler found out that the estate of Kippenberger, managed by Galerie Gisela Capitain, had retained a supply of the original cardboard with which the works could be repaired. Furthermore, Uli Strothjohann, Kippenberger’s collaborator on the works who had made the frames, was willing to do the restoration himself. In fact, he had done a few restorations on works from the Copa series before, perhaps even to the triptych, according to Galerie Gisela Capitain.

In addition to the fact that most restoration cases deal with the amendment of a painting’s surface rather than its frame, “it’s unique in art history that the very artist [Strothjohann] who essentially created the frames could restore the works with the exact same materials used in the first place,” Falk says.

Indeed, Gagosian’s London director, Stefan Ratibor, when reviewing the restored Copa triptych in 2006, said that there was no loss in value and that the paintings “were absolutely in the spirit intended by the artist when they were first painted”, according to his video testimony for the case.

An attempt to use an insurance policy like an ATM machine

The Hollanders returned to Barker at Sotheby’s London to sell the restored works. Their insurance policy allowed them to recoup the difference between the auction price result and the scheduled value—$399,000—should both parties be unable to reach an agreement on loss in value after making a good faith effort to do so.

Yet an email chain offered as evidence in the trial shows that when Barker offered the consignors a high-range pre-sale estimate of £200,000-£300,000 in March of 2006, they asked for a lower estimate to ensure the works would sell. They also requested that the works be offered without a reserve price and that a condition report, which they had written, be published in the sale catalogue noting the restoration of the frames, which Barker declinded to include since the auction house provides its own report.

Barker concluded that the collectors were “trying to prove there had been depreciation of value” when there had not been, according to his testimony for the case. “It would have been harmful for the saleability of the paintings to do that,” he added. The works were offered at Sotheby’s London on 14 October 2006, where they sold for £148,000 ($275,191), allowing them to claim the roughly $181,000 difference between the scheduled value and the sale price less the buyer’s premium.

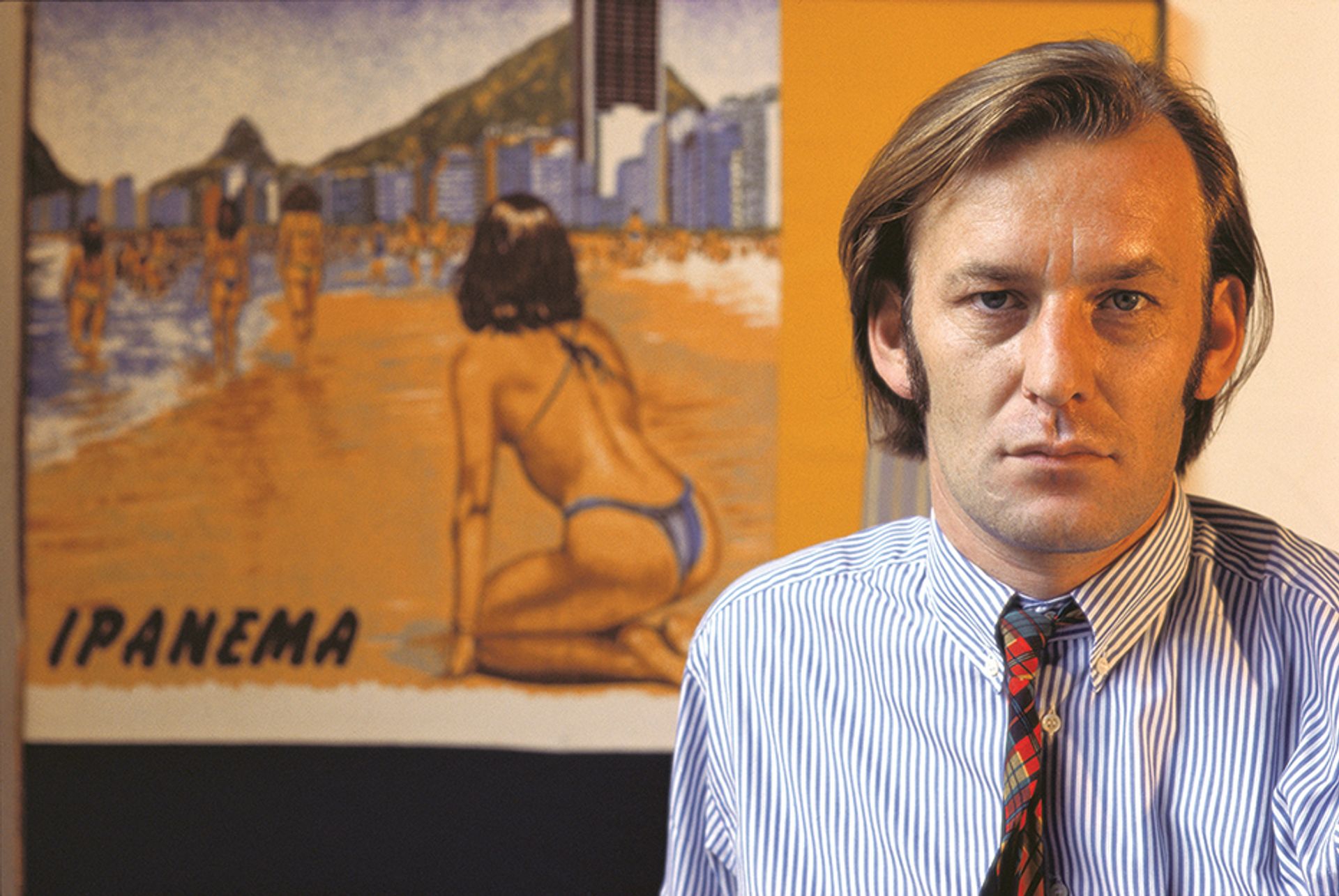

Martin Kippenberger in 1986, the year he produced the Copa paintings Imagno/Getty Images

Rising claim

The collectors took it one step further and filed a bad faith claim against XL Specialty in 2007. In California, when a company has been proven to act in bad faith, claimants have won a small percentage of the value of the defendant company plus attorney’s fees.

After years of appeals and postponements, mostly brought by the Hollanders, a jury trial was set for April 2019. By that time the settlement demand hovered around $95m, including legal expenses. The Hollanders’ lawyer, Richard Friedman, also claimed Gail should be awarded between $100,000 and $500,000 a year for emotional suffering wrought by the case.

“I think what you are looking at here is an attempt to use an insurance policy like an ATM machine,” the defence lawyer Gregory Michael MacGregor said in his closing statements to the jury.

But Friedman countered: “The hope, of course, is that you will not let whatever personal feelings you have about fine art or about rich people influence your decision here.” He added: “What you have been witness to is a 13-year corporate temper tantrum by people who don’t want to be held to their own contracts.”

The jury voted 11 to one against the Hollanders’ bad faith claim, which also nullified the claim for emotional distress, punitive damages and attorney’s fees, though they voted nine to three to award Gail Hollander $19,500 for loss in value—falling just shy of a $19,950 settlement that was offered by XL Specialty before litigation began more than a decade ago.

“Remember what I told you five weeks ago, that this was going to be an interesting case?,” Judge Randolph M. Hammock said to jury members as they levied their judgement. “It probably didn’t start out that exciting, but I think we got there.”

Post-judgement proceedings from the case are still underway; the defence legal representative’s declined to comment while the case remains open. Friedman did not respond to a request for comment.