Three Boston exhibitions are currently confronting migration in dialogue with one another, presenting narratives of mass human movement that cannot be ignored.

At the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art includes around 40 works by 20 artists, many of them ambitiously large in scale. More than United Nations statistics, the individuals whose stories are chronicled here range from those departing from developing countries in search of economic opportunities to those desperately seeking asylum to escape persecution. A mural of yellow block letters set on dull navy by the activist and artist Michelle Angela Ortiz includes text from her interview with Ana, an undocumented mother awaiting deportation from the US who pleads for compassion: “We are human beings, risking our lives for our families and our future.”

The mural faces outward toward the Atlantic waterfront, a closed immigration station from the 1950s, and East Boston, a neighbourhood with a sizable immigrant community. The show evokes the terrifying experience of escaping by sea in a dinghy, and calls to mind an unforgettable line from a poem by Warsan Shire that gives the exhibition its title:

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a

boat

unless the water is safer than the

land

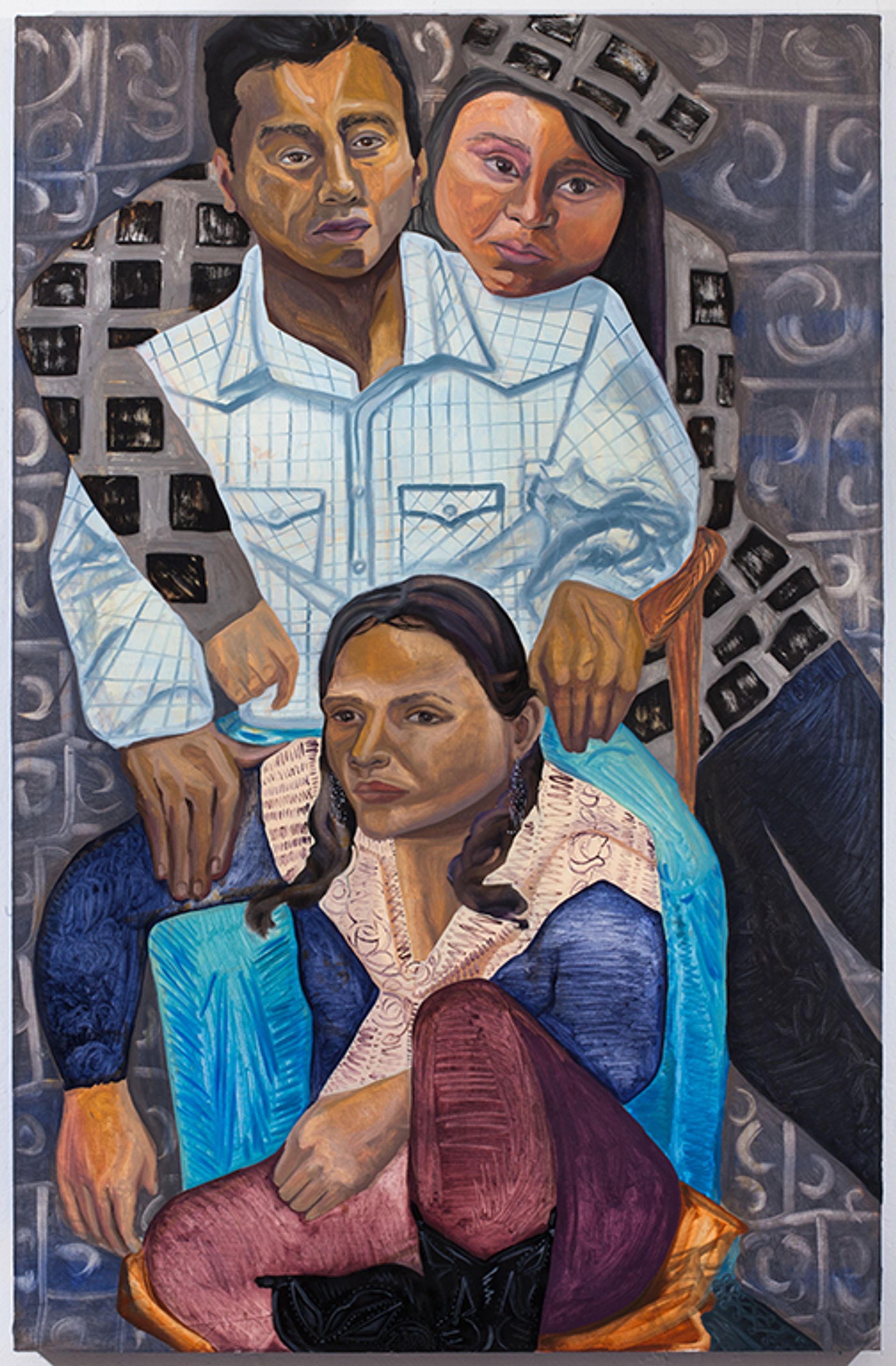

A work not to be missed in the show is Incoming, a surround sound video in which the Irish artist Richard Mosse filmed refugee crossings, rescues, and captures in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East with a thermographic surveillance camera that reduces people to ghostly figures on heat maps. There are underlying ethical questions to the piece, such as whether the artist or museumgoer should be passively observing another human being resuscitated from drowning by a soldier, much less treat it as art. Though Do Ho Suh’s two Hubs (immersive embroidered polyester replicas of the artist’s previous homes stretched on poles) seem too obvious a choice here, Aliza Nisenbaum’s intimate domestic portraits of Veronica, Gustavo, and their daughter Marissa at home in Queens, daydreaming and reading the newspaper, make the experience of an immigrant family universally relatable.

Aliza Nisenbaum's Veronica, Marissa and Gustavo (2013) Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York/© Aliza Nisenbaum

The exhibition Crossing Lines, Constructing Home: Displacement and Belonging in Contemporary Art at Harvard Art Museums features two of the same artists as the ICA, Richard Misrach and Do Ho Suh. It also incorporates older pieces among the 40 works on view, suggesting how the refugee experience transcends our times while offering connections to American slavery and other troubling histories.

Jim Goldberg’s photograph Watching Oprah, Athens Greece from 2004 depicts three men in a temporary shelter zoning out while watching daytime television as they presumably wait to learn whether their applications for asylum have been accepted. In another gallery, Eugenio Dittborn’s 2nd History of the Human Face (Socket of the Eyes) Airmail Painting No. 66 (1989) juxtaposes faces drawn by the artist’s child with mug shots, passport photos and other state images of Chileans displayed beside airmail envelopes that the artist used to smuggle the work across borders during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. With dark humour, the work opens conversations about state control and the ability—even the responsibility—of the artist to resist.

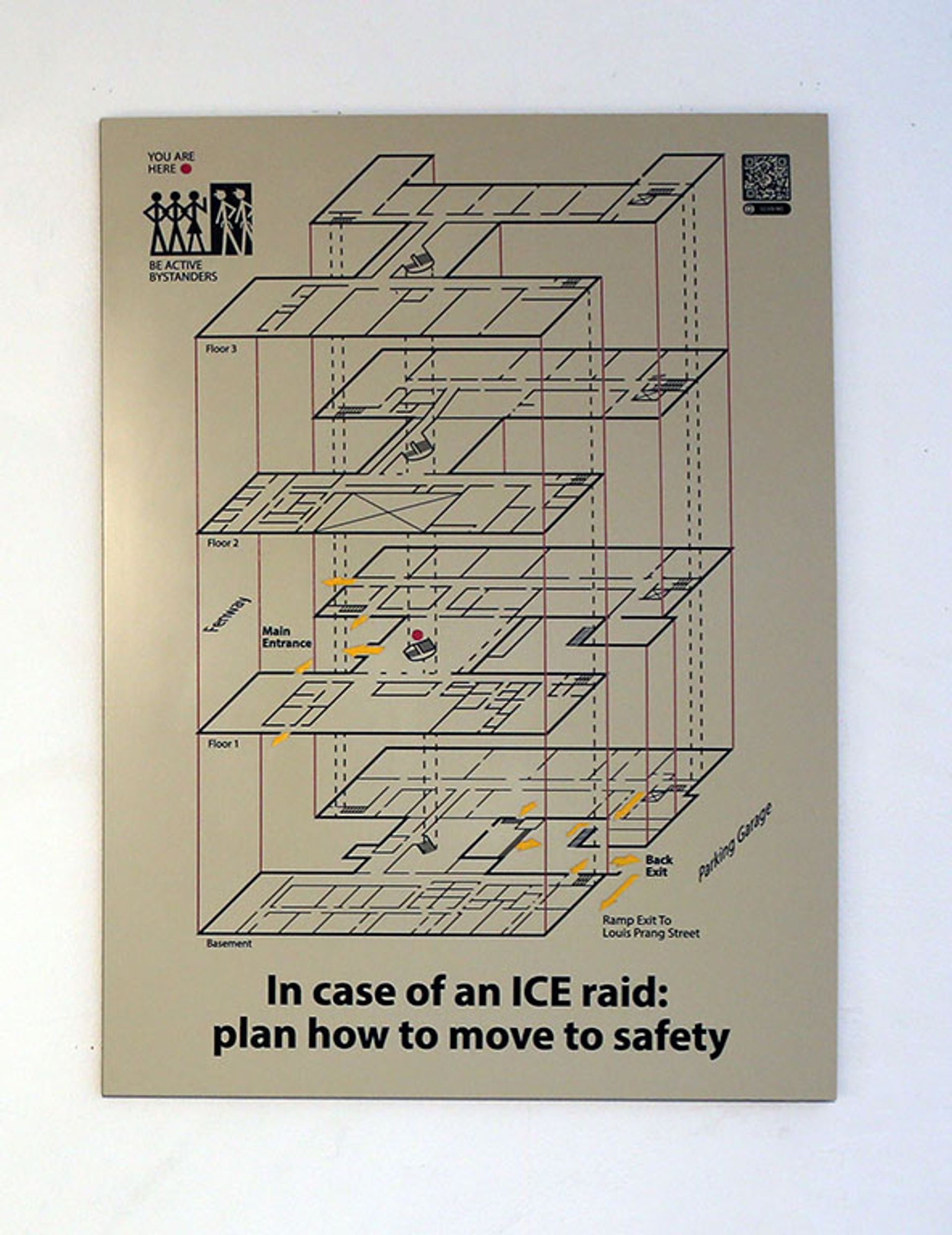

A few miles away underneath a busy stairwell at the School of the Museum of Fine Art (SMFA) at Tufts, a commissioned intervention by Jenny Polak plants viewers in the middle of a raid by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in diagrams with a “You are Here” reminiscent of fire evacuation signs. The text invites us to evaluate our status (hunted or safe) and to choose how to respond, and then specifies the most direct routes to sanctuary from the SMFA.

Jenny Polak's ICE Escape Sign (2019) at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University Courtesy of the artist

Polak, who immigrated to the US from England in 1990, began the ICE Escape Signs series in 2006 in response to what she calls “the very showy, very frightening” workplace raids by the immigration agency under President George W. Bush. Her training as an architect helps to ground the chillingly realistic, blueprint-like diagrams.

Interestingly, the artist’s ongoing series evolved from presenting a primer for fleeing to offering frameworks for resistance, a change that Polak attributes to meetings with students from Tufts’ United for Immigrant Justice Group. In another sequence of the artist’s work installed outside Aidekman Arts Center on Tufts’ main campus, the signs specific to the university are displayed beside older examples from the same series.

It is significant that in the Tufts commissions, there is an imperative to “be active bystanders”, with the stick figures physically blocking the arrests of classmates and colleagues. The installation underlines the curatorial team’s emphasis on social activism, reflecting the university’s openness to undocumented candidates for admission.