Artist applications opened this week for two recently announced monuments in New York that aim to recognise the history of African American families in the city. But while the city forges ahead with its plan to create new memorials to overlooked figures, some historians have called for a reform of the selection and design process.

One of the new memorials will adorn the Central Park landscape in honour of the Lyons family, a group of African American landowners who were part of Seneca Village, a black and immigrants community evicted from their land in the 1850s to make way for the park’s creation. The other memorial belongs to East Harlem’s 126th Street, where a historic African burial ground was found beneath one of the city’s bus depots in the 2000s.

“We traverse towns and cities across this country, and we’re often unaware of the history and the artefacts literally beneath our feet,” Michelle Commander, an associate director and curator at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, told The New York Times, which broke the news on the Lyons monument. “This is a positive step in recognising the history and cultures that have been covered up in the service of having Central Park.”

In 19th-century New York, the Lyonses became known for their advocacy of progressive causes meant to uplift the black community. Maritcha Lyons helped found the Woman’s Loyal Union, which later worked with the journalist Ida B. Wells in anti-lynching advocacy and was a springboard for the National Association of Colored Women. She was also active in the movement to integrate public schools and community spaces in the city. Her father, Albro Lyons, ran what was called a Colored Sailors Home out of the family residency, which later became the target of angry mob attacks during the 1863 draft riot during the US Civil War.

The monument is financed by the Ford Foundation, the JPB Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund. It will be installed in Central Park near the 106 Street west entrance, nearly a mile away from the Seneca Village grounds, which yesterday received updated signage at a dedication ceremony that included African American scholars and community stakeholders.

There are some historians, however, who object to the Lyons monument being placed so far away from the settlement’s former grounds. That includes Jacob Morris, thedirector of the Harlem Historical Society, who called the decision “disrespectful” and “insulting” in comments to the press. Morris has previously criticised a planned monument to American suffragettes , which belatedly added the African American reformer Sojourner Truth after public outcry.

The Lyons project has a budget of $1.15m, which includes all project costs including design services, community engagement, insurance, permits, and engineering. Artists are asked to submit their resumes with work samples and a statement of interest. The city alongside an advisory committee will then select finalists who will receive a $1,500 honourarium to design a proposal. Submissions for the first round of applications is due 1 April 2020.

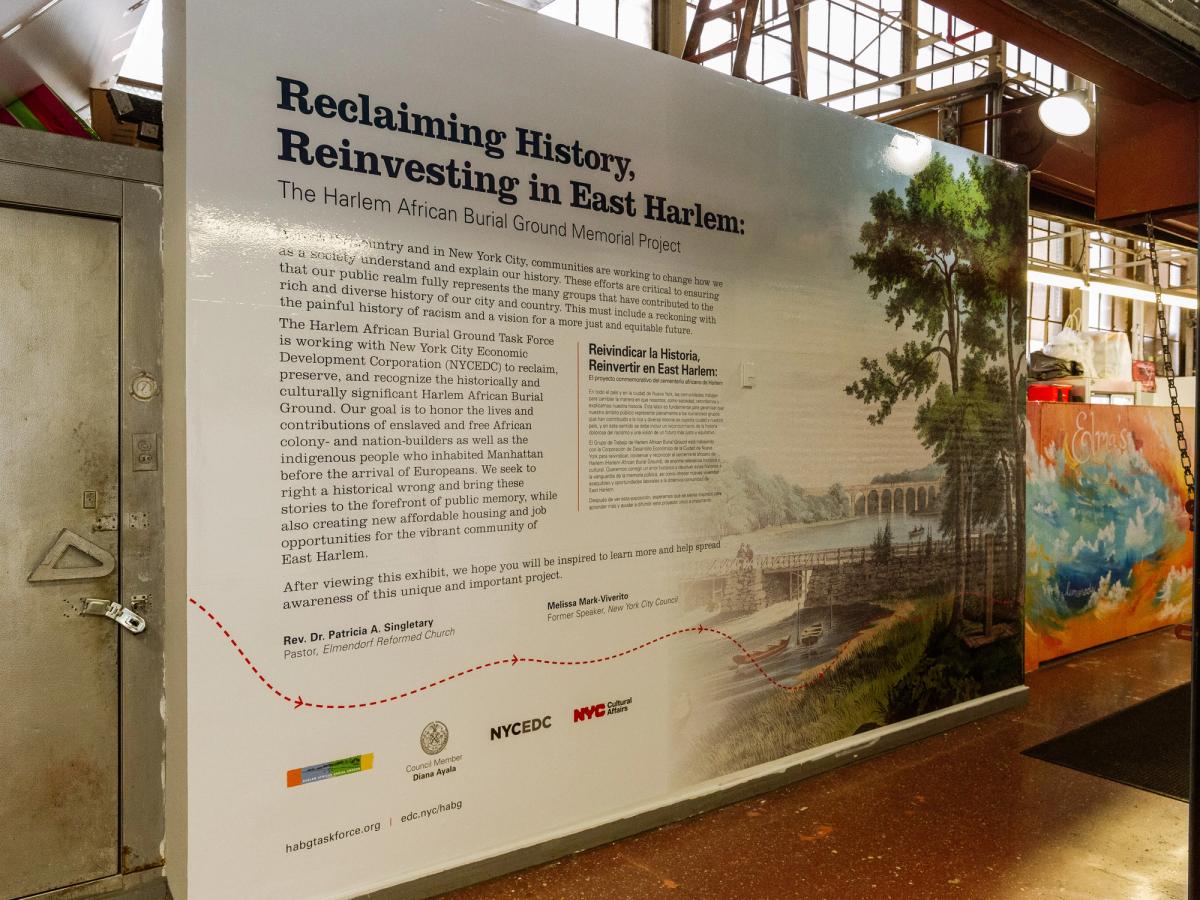

By contrast, plans for the East Harlem’s African burial grounds have taken years to develop. After the site’s discovery in the 2000s, community leaders established a task force in 2009 to advocate for the sacred space sitting underneath the municipal depot. What they discovered were the remains of the only burial ground of the 17th-century Dutch outpost called Harlem Village where Africans were allowed to be interred. The site has changed over the centuries, transforming from church-controlled land to a beer garden, a casino, army barracks, a film studio, and finally a bus depot.

In 2017, City Council approved a redevelopment plan that rezoned the area for residential and commercial use. That change included 18,000 sq ft of space for an outdoor memorial. Additionally, the city will build a cultural education centre next to the monument site. The centre plans to offer public programming, workshops, artist residencies, and a platform for civic leaders to discuss advocacy, literacy, and social justice. The project is being steered by the city’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC), city officials, and local leaders who will review proposals, which are due by 6 January 2020, for an operator of the site.

“This marks a big step toward bringing a new historical and cultural landmark to Harlem, one that will provide public programming while commemorating the African American presence in this area dating back centuries,” said Tom Finkelpearl, commission for the city’s Cultural Affairs office, in a statement. “Honouring those who came before us is essential to building a city that makes everyone feel at home, and we need a partner to help bring this extraordinary, community-driven vision to life.”