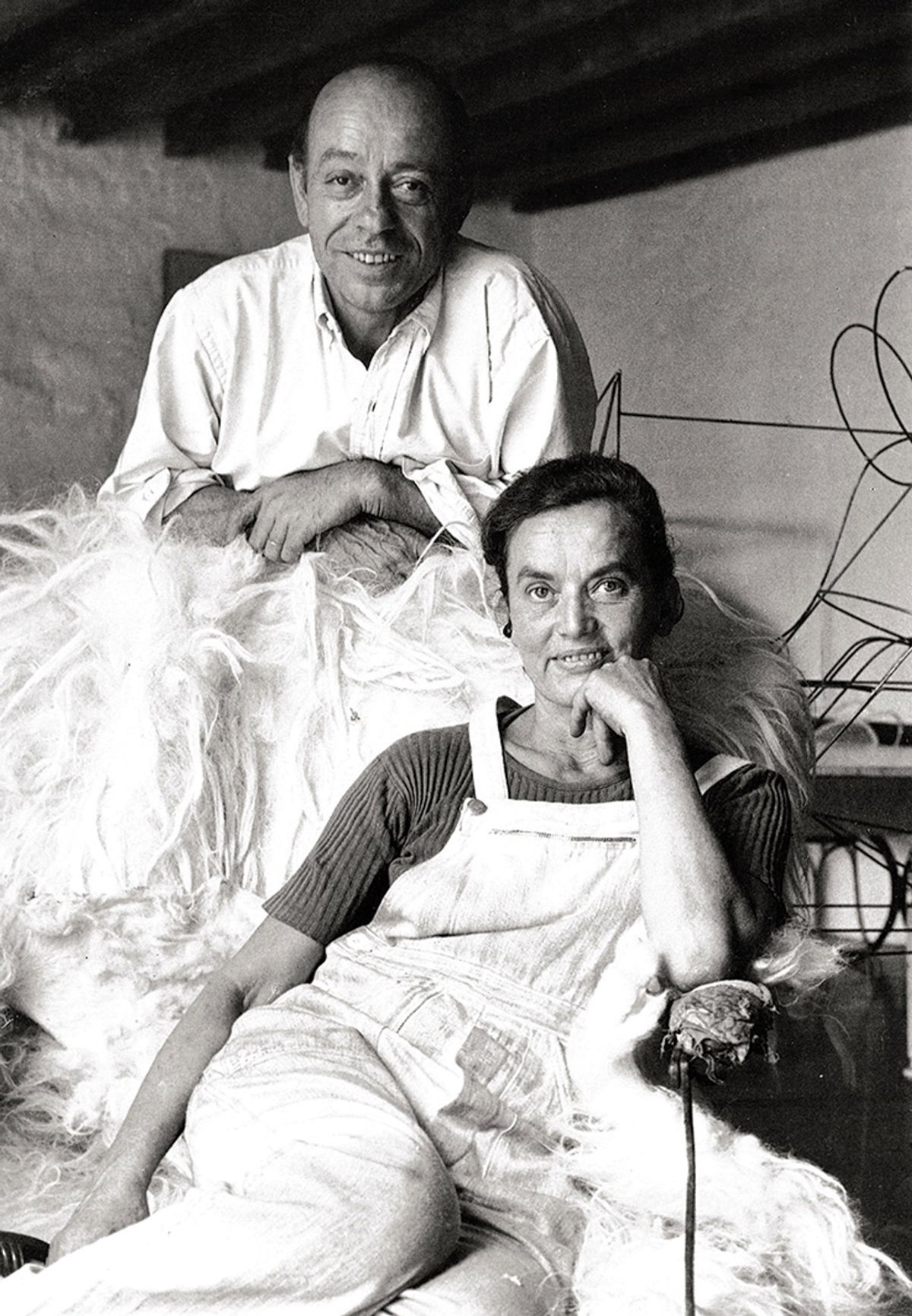

Giant cabbages on chicken legs, oversized gingko leaf table tops, sheep settees. Husband-and-wife duo François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne had a flair for fusing flora and fauna into delightful yet functional works that defied the minimalist austerity of mid-century art and design. He produced large animals with storage or seating uses; in 1966, his “herd” of 24 bronze and wool sheep became his trademark. She combined plants and animals to whimsical ends, often coating organic matter with copper to natural effect; her Man with a Cabbage Head was featured on a Serge Gainsbourg album cover in 1976.

Though they both had their own creative focus—François-Xavier on sculpture and Claude on jewellery that inspired designers like Hubert de Givenchy and Stella McCartney—the French artists often playfully collaborated under the combined alias “Les Lalanne”, attracting fashionable collectors like Yves Saint Laurent and the Rothschilds.

Following Claude’s death earlier this year (François-Xavier died in 2008), around 280 items from the couple’s private collection will be auctioned by Sotheby’s in Paris on 23-24 October. Drawn directly from their home near Fontainebleau, where they lived for almost 50 years, the lots—200 of them authored as Les Lalanne—are expected to fetch up to €22m (£19.7m). Demand for their work, however, has been on the rise for the past decade. “Their work has always straddled art and design effortlessly. That’s why their prices have gone up—there is cross-market appeal,” says Jeremy Morrison, the European head of design at Christie’s and self-avowed Les Lalanne fan. “There’s no particular style to their work and they didn’t want to be in a group with other artists. They are distinct.”

What makes the couple’s designs captivating may be their quirk, but what has made them collectible is their distinctive ability to blend modern techniques with traditional craftsmanship into what the sculptor James Metcalfe described as “objects to live with”. The duo saw no difference between high art and artisanship and moved between the two fluidly. To do so was a radical notion in post-war Europe, where artistic abstraction and industrial production reigned supreme.

The couple, who met in Paris in 1952 when Claude went to an exhibition opening of François-Xavier’s paintings, ran with a nonconformist artistic crowd, Metcalfe included, as well as many surrealists like Max Ernst, Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle. The surrealism influence is evident in their fanciful statuary, pronounced in Choupatte (cabbage feet) sculptures and hippopotami-shaped storage units, to name a few. Morrison notes they were also prolific, exhibiting under their own title since the mid-1960s and each working up until their respective deaths, Claude producing work well into her 90s.

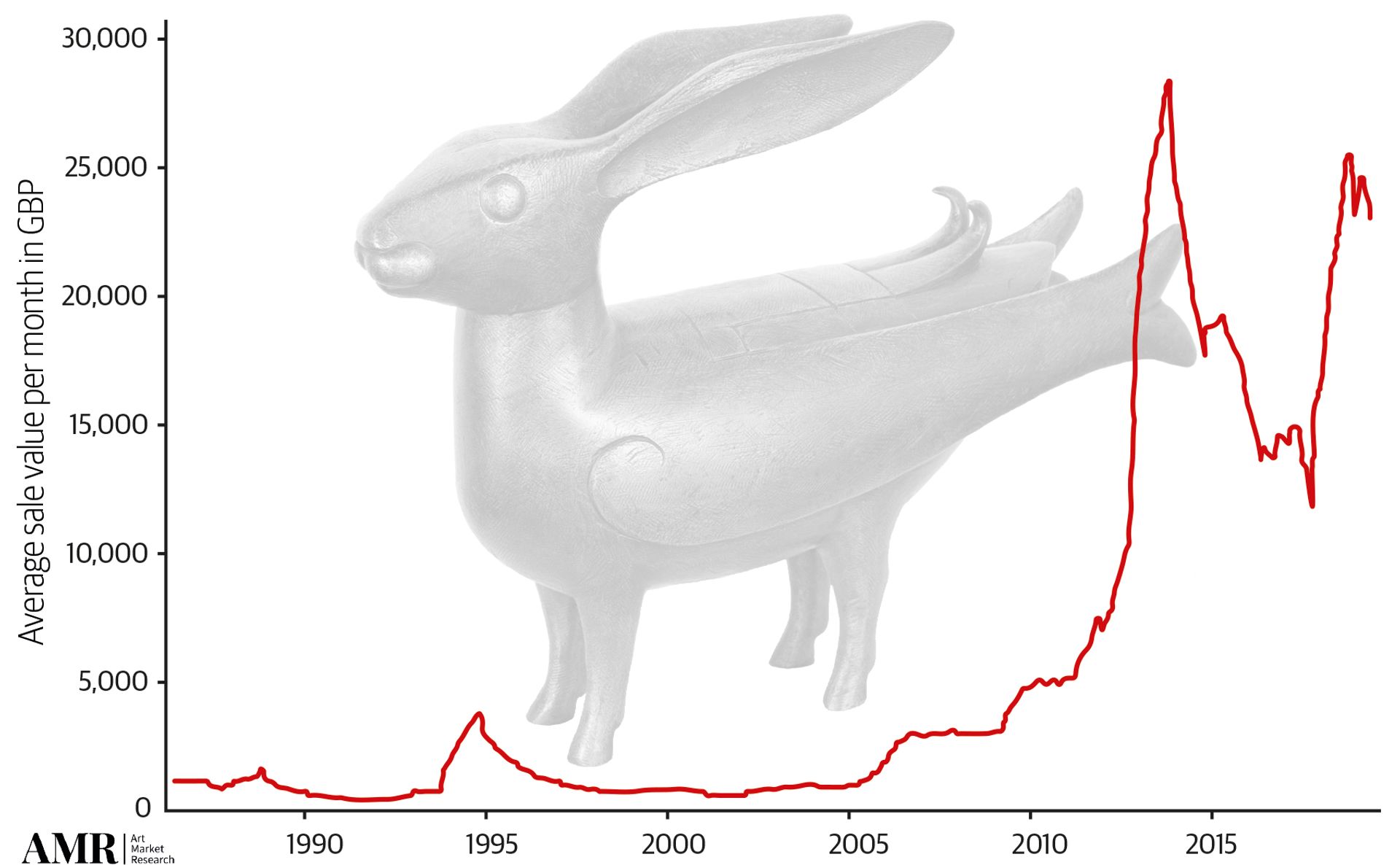

Prices for Les Lalanne works vary, often depending on size, but they have been rising ever since a pivotal 2009 sale at Christie's

Prices

It was Sotheby’s that organised the first sale dedicated to Les Lalanne in Paris in 2015. More than 60 lots achieved €4.8m, far surpassing estimates; the highest price went to the monumental Lapin de Victoire by Claude, sold for €903,000 (with fees). The recent world auction record for Les Autruches Bar (1967-70) from the Jacques Grange collection sold for €6.2m (with fees) in 2017, also at Sotheby’s in Paris. Alberto Giacometti is the only other designer who has fetched prices at auction in that ballpark. That being said, Morrison notes the prices vary, often depending on size. On the smaller end, “you can easily get a good Lalanne piece for £20,000-£30,000”, he says.

Known primarily for his exclusive representation of the major European Surrealists in the US, Alexandre Iolas was the first dealer of Les Lalanne in the 1970s, selling works to important collectors like German industrialist and playboy Gunter Sachs and head of Fiat Gianni Agnelli. It is London’s Ben Brown, however, who grew their collector base when he started representing the duo in 2004 after being introduced to their work via Iolas’s last romantic companion—a neighbour of the Browns at their home in France—before the former’s death in 1987.

Prices for their works have risen “slowly but surely” since the 1990s, according to Brown, though sales had slumped after a brief bump in the 80s. “It was what you might call a domestic hiccup,” he says, “an issue of the dealership structure or the lack thereof”, as Les Lalanne were working directly with the auction house Artcurial after Iolas’s death, “and that coincided with the art market’s downturn, especially in Paris”.

Since he took them on, their prices have gone up “by around 1000%”, Brown says, noting the pivotal 2009 Yves Saint Laurent sale at Christie’s as a major turning point. More iconic works, like a small Choupatte or crocodile chair by Claude or one of François-Xavier’s many Mouton, can range from $300,000 to $1m. “Basically, you can just add a zero to the price of any of their works now compared with when I started working with them,” Brown says. With supply of François-Xavier’s work on the decline and Claude’s recent death, he anticipates a further surge in sales. Indeed, at Design Miami in June, two months after Claude’s passing, Galerie Mitterrand sold nearly its entire exhibition of the late artist, with sales totalling more than $1m.

Choupatte (2014-2015) by Claude Lalanne Courtesy Sotheby's

Demand

While the couple were well known among their artist peers from the start, their work came to a wider audience after they became friends with a fresh-faced 25-year-old Saint Laurent, who had just left Dior to found his own fashion house. This friendship was marked by two major commissions for Saint Laurent’s home that he shared with his partner, Pierre Bergé: first, a sculptural brass and crystal lounge bar by François-Xavier (started in 1964 and delivered in 1965), and ten years later a monumental set of salon mirrors made by Claude.

When Christie’s held a sale in 2009 of Saint Laurent’s possessions following his death, it included the Bar YSL and Salon des Miroirs. Both exceeded ten times the estimate, “adding rocket fuel to their market”, according to Morrison. The couturier also worked with Claude, whose metal castings from the body of supermodel Verushka were used in the designer’s Empreintes collection of 1969.

The upper echelons of Parisian society, like the Rothschilds, as well as English art collector Pauline Karpidas, were buying up their work via Iolas. But Brown began selling to a larger international coterie of fashion buyers, making works by Les Lalanne an “in” thing to have. Brown also introduced Les Lalanne to the New York dealer Paul Kasmin, who began representing François-Xavier and Claude in the US in 2007. “He made the market for them in the US,” Edith Dicconson, a director at Kasmin gallery, says. Coinciding with the Christie’s YSL sale in 2009, Kasmin orchestrated the installation of numerous Les Lalanne sculptures up and down New York’s Park Avenue, including a large-scale bronze apple sculpture by Claude Lalanne and François-Xavier’s last sculpture, Singe Avisé, a cross-legged monkey with a thoughtful visage.

“It was one of the most important exhibitions of [their] sculptures,” says Florent Jeanniard, the European head of 20th century design at Sotheby’s. Kasmin also followed this by the largest outdoor exhibition of their work at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida, in 2010. A major show at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs, designed by architect Peter Marino—also a collector of their work—that same year “had a huge impact as well”, Jeanniard says.

Les Lalanne's popular sheep sculptures are more coveted now than ever before © CAPUCINE DE CHABANEIX FOR SOTHEBY’S

Collectors

Les Lalanne works are now in institutional collections including the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York, the Museé Nationale d’Art Moderne/Centre Georges Pompidou and the Museé d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. A Lalanne exhibition is planned for the summer of 2020 at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Besides Saint Laurent, other key collectors include the fashion designers Valentino, Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs and Karl Lagerfeld, “who bought a lot of [François-Xavier’s] paintings”, Brown says, adding that the former actress and Warhol superstar Jane Holzer also became a big collector early on in the US. French business magnate François-Henri Pinault, chief executive and chairman of Kering and Christie’s, is also a fan.

In 2013, the exhibition Sheep Station inaugurated Getty Station, a new public art programme located at the former Getty filling station in West Chelsea; it drove demand for François-Xavier’s Mouton through the roof. “They became like a gateway drug for collectors,” Dicconson says. “Now people are collecting them en masse,” she adds, noting that it was nearly all new collectors—all of whom were American—who bought out the show Kasmin hosted last March, just before Claude’s death.

Pitfalls

Collectors flock consistently to Les Lalanne’s sheep. “Surrealist animals in general by François-Xavier are highly sought after—monkeys, rhinoceros, bears, ostriches, dogs and cats—and the demand is stronger when the sculptures can also be used as desks, lamps or bars,” Jeanniard says. “This is the same for Claude’s works with her mirrors, armchairs, benches, stools or coffee tables.”

Morrison says there is little price discrepancy between older and newer editions, “but as their market matures, we’ll see”. So far, few issues with fakes have been reported. “They had a very high standard and good galleries supported them,” Dicconson says. “People will be looking to the upcoming sales to see what happens with their prices.”

Sotheby’s two-day auction this month has caused a stir in France, with some suggesting the couple’s private collection and home should be transformed into a museum or foundation. Yet Jeanniard has dismissed the criticism, saying that the couple’s four daughters must sell the works to pay death duties.