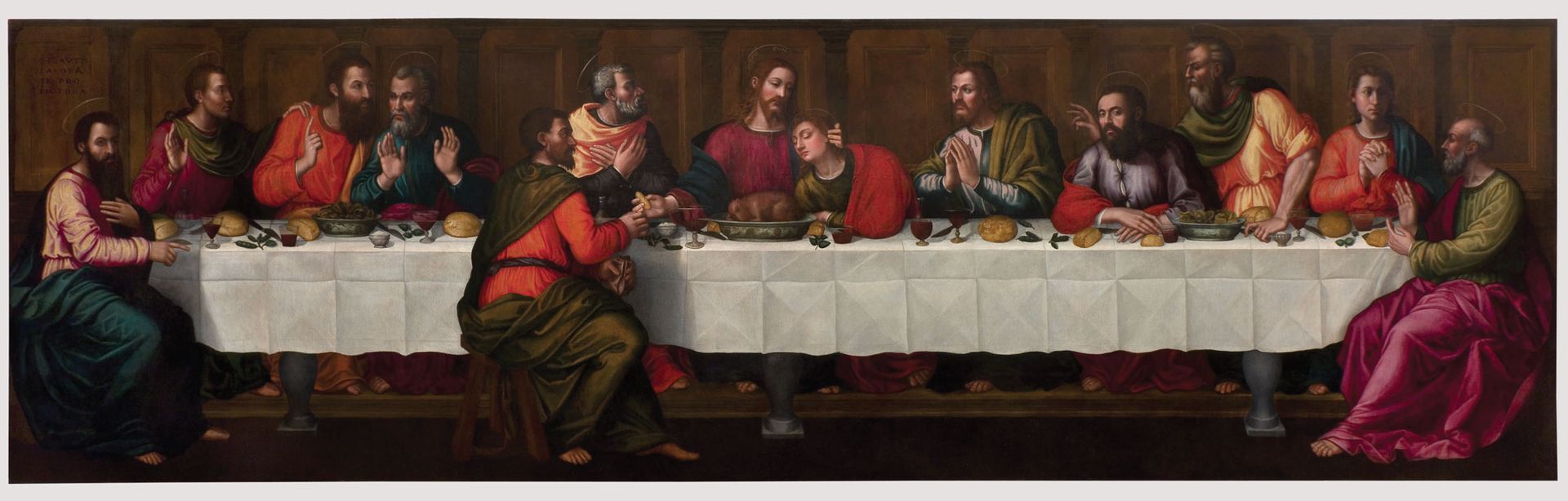

What is believed to be the only Last Supper of the Italian Renaissance painted by a female artist has gone on public view for the first time after a painstaking four-year restoration. Measuring almost seven metres wide and two metres high, the 450-year-old canvas at the Museo di Santa Maria Novella in Florence is also the largest work that survives by Plautilla Nelli (1524-88), a Dominican nun who is finally receiving her art-historical due after centuries of obscurity.

Nelli is among a handful of women included in Giorgio Vasari’s 16th-century biography, Lives of the Artists. He described her self-taught skills as “a nun and now Prioress… beginning little by little to draw and to imitate in colours pictures and paintings by excellent masters”. Having entered the covent of Santa Caterina in Cafaggio at the age of 14, Nelli went on to establish a workshop of nuns who took on church commissions and private clients as well as producing large-scale Biblical scenes for their own religious contemplation.

While an Adoration of the Magi in the convent church was lost, Nelli’s Last Supper in the refectory endured Napoleon’s suppression of religious orders, the expropriation of church property after Italian unification, three decades of the 20th century spent rolled up in storage and even the catastrophic flood of the river Arno in 1966. In 1817, the painting was transferred to the monastery of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, where it hung for many years in the friars’ own refectory.

The painting, created for the convent refectory, endured the dissolution of religious orders and even the catastrophic flood of Florence in 1966 Photo: Rabatti & Domingie

Preserving the work has been a flagship project for the US-registered Advancing Women Artists Foundation, which has restored 65 pieces by historic female artists in Florence over the past decade. AWA’s crowdfunding campaign in 2017 raised $67,000 towards the conservation of Nelli’s Last Supper. A further initiative saw the 12 apostles in the painting “adopted” by donors for $10,000 apiece (unpopular Judas was saved by ten donors giving $1,000 each).

Sister Plautilla added a striking inscription beneath her signature on the Last Supper—“Orate pro pictora”, pray for the paintress. But conservator Rossella Lari’s efforts to clean and reconstruct the picture lay bare the collective nature of Nelli’s work, says AWA’s director, Linda Falcone. “Within these seven metres you can see different painterly hands, so it’s canvas proof that she founded this all-women workshop inside her convent.”

Conservator Rossella Lari stripped away much of the heavy overpainting left by previous restorations Photo: Camilla Cheade

Lari stripped away much of the heavy overpainting from previous restorations, studying “every single Last Supper table from the 15th and 16th century in Florence” to fill the gaps in the composition, Falcone says. Nelli chose to depict the revelation of Judas’s betrayal of Jesus, possibly emulating Leonardo’s dynamic 1495-98 fresco for Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. But her rendition is also “much more terrestrial and nurturing than other Last Suppers”, Falcone observes, with lamb and salad served in fine Chinese porcelain and well-ironed creases in the tablecloth.

In a catalogue published by Florentine Press, Lari writes that Nelli’s “powerful brushstrokes” and chiaroscuros indicate “a great sense of energy and determination”, although inconsistencies of perspective and proportion betray her lack of formal art education. As a woman and nun, Nelli would have been unable to study live models in a master’s workshop, and is thought to have relied instead on printed manuals and other artists’ works. Yet she depicted the apostles at life size with keen attention to anatomical details such as a muscled arm, veined hands and forehead wrinkles.

It is hoped that unveiling Nelli’s masterpiece will spark further research into her technique, with an academic conference planned at the Santa Maria Novella museum on 12 November. Since AWA first began conserving her works, the number of pieces attributed to Nelli has risen from three to around 20. “It’s the dialogue we want to trigger,” Falcone says. “The work starts in the restoration studio but then it’s a conversation for others to take up.”

Nelli depicted the Last Supper with keen attention to details such as the apostles' forehead wrinkles, salad served in fine Chinese porcelain and well-ironed creases in the tablecloth Photo: Rabatti & Domingie