The photographer Jean-François Jaussaud made a perilous pact with Louise Bourgeois when he asked to take her photograph in 1994. “Louise was difficult, and she put a condition on my work. She said: ‘If I don’t like your pictures, I can destroy everything. If you agree to that, you can do the pictures.’”

It was a big risk. Jaussaud eventually made the journey to New York from Paris in April 1995, armed with a commission from the magazine Connaissance des Arts. And the shoot in Bourgeois’s Brooklyn studio started rockily. He hadp set up a dynamic shot-—“with an assistant, lights, the flash, everything”—with Bourgeois and her sculpture Eyes (1995), two orbs that, like so many of her works, elide vision with sexual organs. “But then, when she came for the portrait, she just didn’t feel good. She said it would not be possible.” She even told him he was “stealing” her image and left the room. Jaussaud feared the worst, but five minutes later Bourgeois was back, this time donning a white baseball cap. “She said: ‘Now I am protected you can do the picture.’ And she was smiling.”

Fortunately, when he showed her the pictures, “she loved them”, he says. “And she invited me to return: ‘You can come back when you want.’” Bourgeois never again asked to approve one of Jaussaud’s photographs, and over the following 11 years, whenever he was in New York, he would visit her at the studio or her home in Chelsea. He would telephone early in the morning, before the staff arrived. If she agreed, they would spend five minutes chatting before Jaussaud wandered at will. “I was in the house all day and she would be working,” he recalls. “Sometimes she came and I’d do a portrait, sometimes she was looking at what I was doing, sometimes I was just alone.”

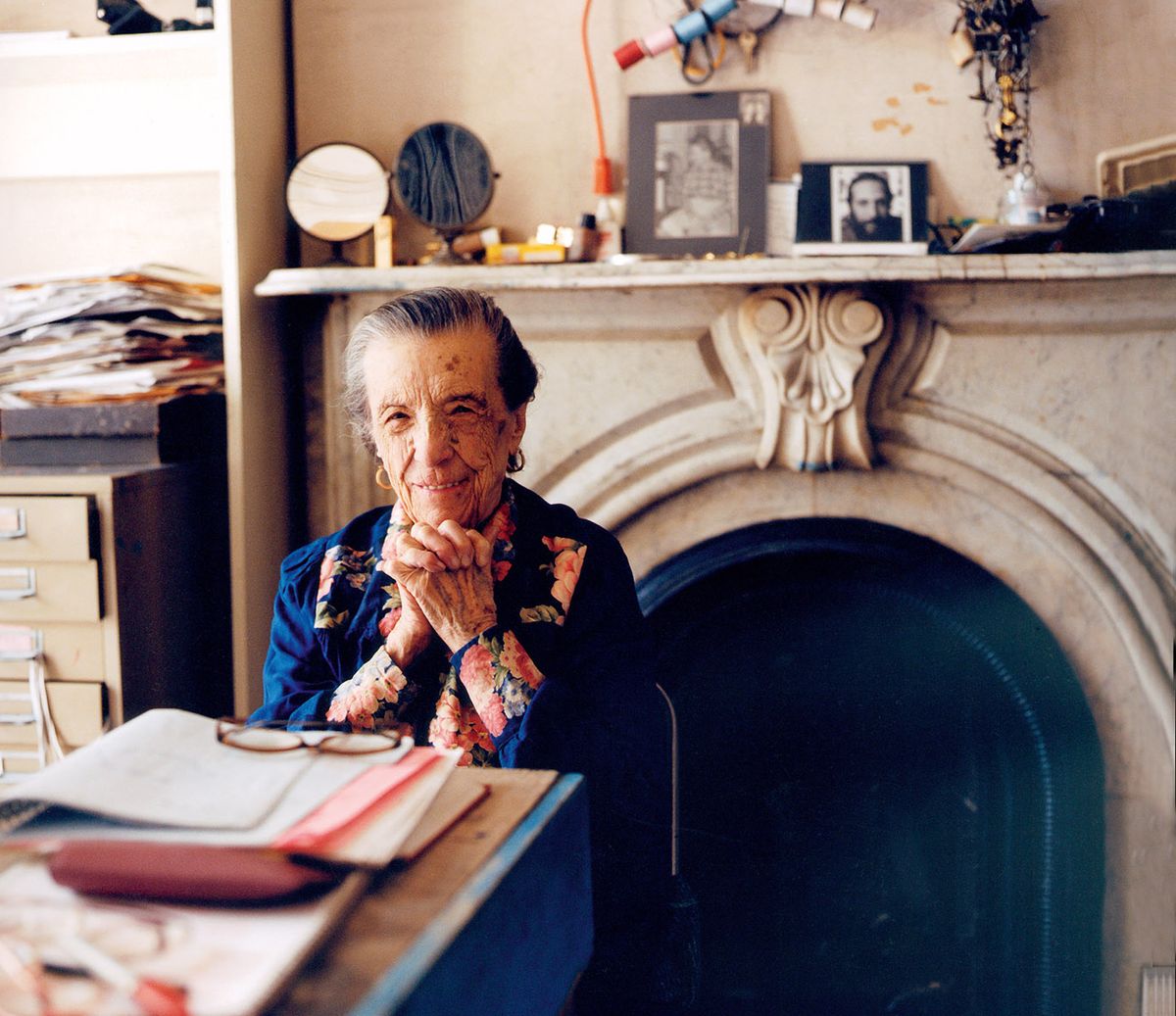

The results of those many visits are the subject of Jaussaud’s book, Louise Bourgeois: an Intimate Portrait, which was published earlier this month. We see Bourgeois from that first session, with Eyes, a knowing smile beneath the baseball cap that was her protection, or towered over by one of her Spiders. Elsewhere, she sits drawing at her desk in the cluttered office. Alongside the portraits are interiors: the cramped basement studio, the walls covered with drawings and texts—what she called her “pensées-plumes”—and the library that was her husband Robert Goldwater’s favourite room. Then there is the bedroom the couple shared until Goldwater died in 1973—Bourgeois had not spent a night there since his death. Jaussaud gained access to this room “only at the end”, he says. The room where Bourgeois slept for the last four decades of her life until she died in 2010 “was really not a bedroom, just a very simple bed, with no comforts at all”, surrounded by bookshelves.

Although there are short entries by Jaussaud, as well as by the art historian Xavier Girard and the Louvre curator Marie-Laure Bernadac (the latter organised Bourgeois’s Centre Pompidou retrospective in 2008), most of the texts are quotations by Bourgeois or Jaussaud’s photographs of her manuscripts. This idea came from Jerry Gorovoy, Bourgeois’s assistant and collaborator for many decades. “He invited me to come to her archives because they have a lot of written material,” he says. “And I think it’s stronger than having a critic or a curator analysing the work.”

Gorovoy’s idea was effective: in uniting the ideas and musings in Bourgeois’s quotes from across her life with Jaussaud’s photographs of her enigmatic presence, her atmospheric interiors and her sculptures and drawings, the book evocatively captures the world of an artist for whom, as Jaussaud says, “art and life were the same thing”.

• Jean-François Jaussaud, Louise Bourgeois: an Intimate Portrait, Laurence King, 192pp, £30 (hb)