On May 16, a group of 26 honours middle school students and their teachers visiting the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston on a self-guided field tour reported multiple incidents of racism, including being closely followed by security guards and crossing paths with a white patron who hissed an expletive as they entered a gallery.

The MFA responded with a public apology and promised to take steps to become more welcoming to all audiences. The museum recruited a former Massachusetts attorney general, Scott Barshbargar, to conduct an investigation; the student/teacher group from Helen Y. Davis Academy secured the pro bono services of the nonprofit Lawyers for Civil Rights Boston; and the current state attorney general, Maura Healey, opened an inquiry as well.

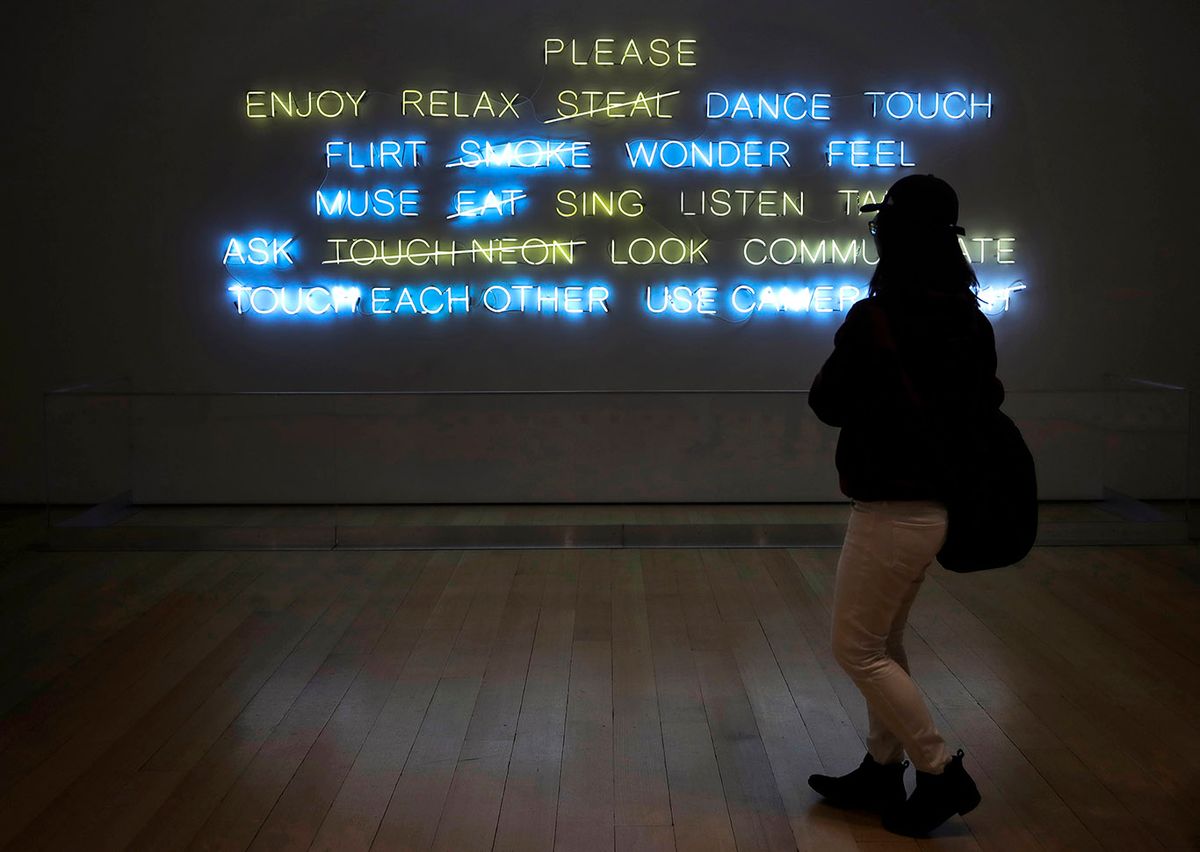

Although the investigations continue, the museum recently invited a select group of educators, politicians and journalists to preview some new materials and procedures. “It’s on us to make sure people feel comfortable here,” the museum’s chief of learning and engagement, Makeeba McCreary, said in an interview. “It’s not on them. And part of being comfortable—and we learned this from listening to teachers, educators, artists, and family members—is you tell people what to expect.” She indicated that the MFA faces a long journey toward meeting its goals but declares that it is committed to becoming more inclusive in both its programming and its hiring. “There are things that are part of our norms that I think we need to remove,” she said. “We should be reflecting the city in terms of our staff. People should come in and see people who look like them.”

Local politicians, journalists and educators poured into a seminar room for the session. Strikingly, just one student was on hand, Jennifer Rosa, a teen scholar at the MFA and a host of a new video, Field Trip 101, that was screened that day and will be shown to students before museum visits to provide a sense of the museum’s culture and to impart guidelines.

“You will see guards rotating through the galleries to keep you and the art safe,” a narrator explains. “Museum security wants to ensure a safe and fun time for everyone. The guards are very helpful and knowledgeable. Did you know that many of them are also artists?”

McCreary and colleagues announced that prior to a group visit, teachers will now receive a questionnaire and a handout (including a direct number for Security Services, should chaperones need help or want to report concerns) and that the museum has created a gallery hosts program that will soon place trained peer educators with radios in high-traffic galleries so that even self-guided groups are not entirely on their own. The museum has also conducted introductory training sessions to detect and work against unconscious bias among staff members and volunteers who deal with visitors, and it will soon post a job description for a senior director of inclusion.

The changes are the result of input from multiple focus groups that McCreary and colleagues convened with locals, including many prominent members of Boston’s African-American community, to address the topic of racism and privilege in traditional museum culture. The institution has committed itself to a long-term strategy for institutional change, yet the shift does not appear to be mending ties with those involved in May’s incident.

The morning of the preview, Lawyers for Civil Rights Boston released a statement pointing out that the Davis students had not been invited and that their requests to the MFA administration had gone unmet. In an interview, Oren Sellstrom, the organisation’s litigation director, said that the students had requested counselling to deal with what happened at the museum but that the museum never responded. “This is a cash-strapped school and has no school psychologist,” Sellstrom said.