Although his pieces have many of the trappings of street art—monumental scale, wheatpaste adhesive, a populist message—the French artist JR sees his work as “more like a sociological experiment”. He doesn’t “relate to the term street art”, he says. “There are categories like museum art, street art, public art and outdoor art, but in the end these are just marketing names.”

Yet seeing his work transferred to a museum setting gives him pause. “I always see that transition from street to museum as a challenge because it can completely change the frame and context of the piece,” he says. “It’s interesting to see how artists have found ways to address that.”

JR himself has wrestled with that challenge in his most comprehensive US exhibition to date: JR: Chronicles, opening on 4 October at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. Featuring murals, photographs, videos, films and dioramas, it spans nearly two decades of work, while underlining how thoroughly today’s museums have mastered the mechanics of taking street art indoors.

The show includes images and videos of the artist’s earliest interventions as a photographer and graffiti artist on the streets of Paris, some of which have never been shown in the US. The aim is to allow viewers to “rediscover how I became an artist, because I didn’t know that was going to happen to me or that there was such a job—I had no knowledge of the art world or museums or galleries,” JR says. “When I look back, I don’t know what I was thinking. I just knew there was some bigger morality to what I was doing and then everything just happened.”

Among the earlier works profiled in the show are videos and photographs of the Face 2 Face (2007) project, in which the artist photographed men and women on either side of the Israeli-Palestinian divide in Jerusalem. Pasting the images together in a large-scale format, JR sought to demonstrate how two communities are indistinguishable on the surface. Curators have also gathered archival videos and photographs of the 2009 project, Women Are Heroes, for which the artist plastered portraits of local women in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro to denote their status as pillars of the neighbourhood.

JR Andia/Alamy

Created equal

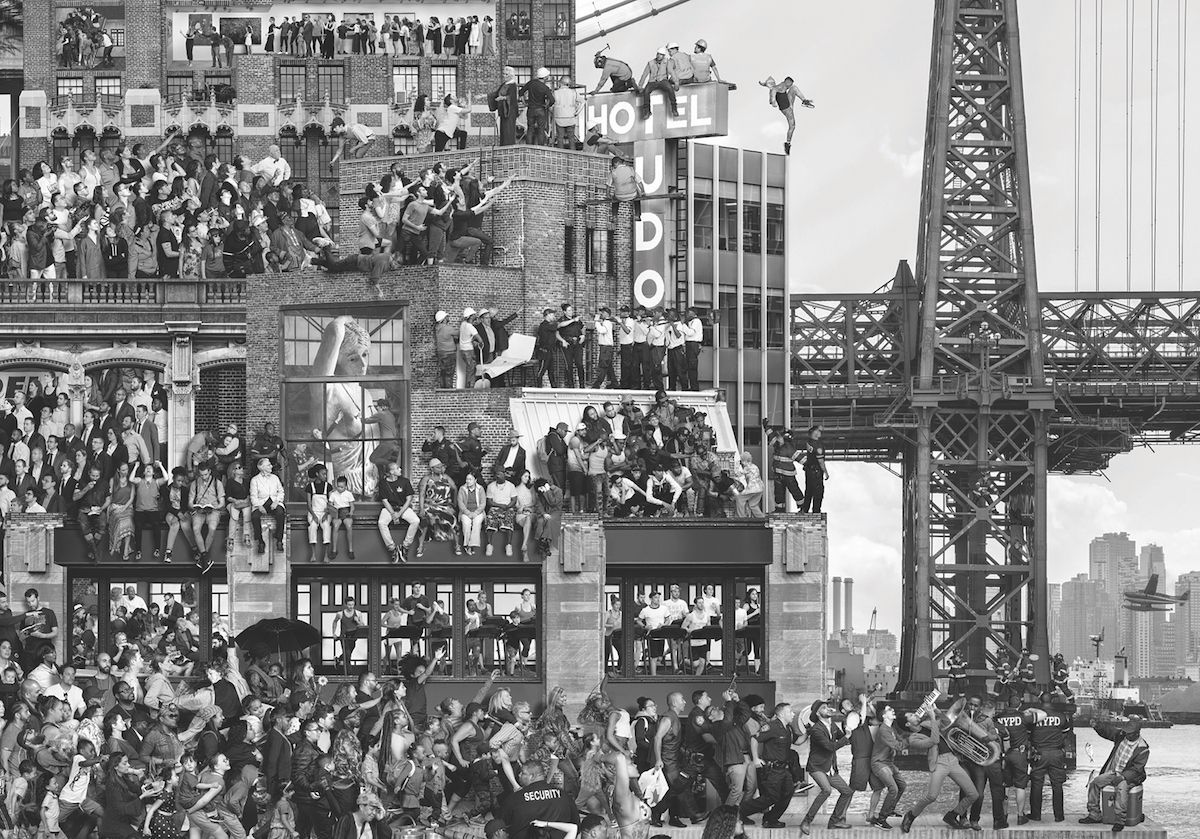

But the pièce de resistance is The Chronicles of New York City, a vast new mural amalgamated from collaged photographs of more than 1,000 people. Setting up a studio in a truck, the artist has spent months crisscrossing New York’s five boroughs and photographing people on the street and asking them to tell their stories as he records the audio.

“It can be someone who has a selling stand, a person who is walking home, someone jogging, or whoever accepts to be part of the project,” JR says. “There is no selection and no one is more important than the other. Everyone is equal in this group photo.” He says the work was inspired by murals by Diego Rivera that capture a community, a neighbourhood, or a city.

The Brooklyn Museum has a history of showcasing artists that create work in a public space, says one of the show’s curators, Sharon Matt Atkins, the museum’s director of exhibitions and strategic initiatives. “Whether or not they define themselves as street artists,” she says, “we aim to think broadly and have an expansive view of creative expression.”

Among the museum’s past shows devoted to artists of the genre are a blockbuster Jean-Michel Basquiat survey in 2005; the landmark Graffiti show in 2006, profiling artists including Melvin Samuels and John Matos, who helped bring street art into the mainstream art world; a Keith Haring retrospective in 2012; and a 2014 solo exhibition for the mixed-media artist Swoon.

What gives certain street artists credibility for curators? For the Brooklyn Museum, it is the socially conscious quality of the work, and the ability of the artist to transcend traditional notions of what belongs in a museum. “It’s about the work aligning with our commitment to community and pushing the boundaries of art, or at least the way art museums have categorised art production and artistic merit,” says Drew Sawyer, the museum’s Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian curator for photography, the show's other curator.

In the end, “street art is no different from most art that is presented in museums”, Sawyer says. “Whether it’s an African mask, a Renaissance icon, or even most of the historical avant-garde, many works of art that were created for other contexts—and sometimes in direct opposition to art museums—have ended up in museums.”

For JR, it is the storytelling behind the work that translates well to a museum. “Over the years, I’ve spent a lot of time and energy documenting everything—even when there was no social media, and when I didn’t know why I was doing it—because how people interact with and react to the work on the streets is the work itself,” JR says. “In the end, people can define you and your practice in many ways, and I’m not going to start a fight about it—I have to let it be.”

• JR: Chronicles, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 4 October-3 May 2020

• JR: The Chronicles of the New York City—Sketches, Perrotin, 11 September-26 October