In 2012, Liza Essers was taken to court by the South Africa president Jacob Zuma, his children and the ANC ruling party. Her supposed crime? Showing a painting, The Spear by Brett Murray, which depicted Zuma with exposed genitals. The painting prompted 5,000 ANC supporters to march on the Johannesburg premises of Essers’ Goodman Gallery, some carrying placards reading “White hate blacks” and “Draw your white father naked, not our president”. The gallery responded with its own slogan: “We respect your right to protest.”

The government demanded the painting be taken down. Essers refused. They settled out of court, though the painting was taken down after it was defaced. “We need to stand up for freedom of expression and against censorship,” she says. “It was a particularly dangerous moment in South Africa, because a number of journalists were being censored and our constitution was being challenged. It’s a moment I’m very proud of.”

Brett Murray, The Spear, 2012. Before and after it was defaced Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

South Africa today is “going through a very rough time”, Essers says. In retrospect she stands by her decision to show The Spear, despite receiving death threats. “There was massive corruption under Jacob Zuma, and we’re now in a recession,” she says. “There is huge unemployment, 50%, and the new president has a huge task ahead of him to try and take the country out of this mess. But I am hopeful.”

My life is in South Africa and I have a role to play in the cultural landscape. I have no intention of emigrating

Goodman Gallery opened in London in September (adding to locations in Cape Town and Johannesburg), and some assume Essers will move there—an assumption she forcefully rejects: “My life is in South Africa, and I have a role to play in the cultural landscape. I have no intention of emigrating.” Instead she has employed Jo Stella-Sawicka to head up the London space—it took her 18 months to persuade the artistic director of Frieze London to join. “I don’t often take no for an answer,” she says. “I am just very persistent.”

Essers is the child of immigrants. Her mother was a first-generation Libyan refugee, her father the child of Lithuanian immigrants. Goodman Gallery’s focus on social change is “linked to my personal history”, Essers says, but political and social engagement through art was the gallery’s founding principle. It was started in 1966, during the apartheid era, by Linda Givon (née Goodman), unusually exhibiting black artists and welcoming black visitors at a time when they were banned from state museums.

Kapwani Kiwanga, Rumours that Maji was a lie (2014) © Romain Darnaud/Jeu de Paume

After university, Essers worked for Accenture as a strategic consultant but quit the corporate world at 29—“my Saturn return”, she says, referring to the theory that people often make major life decisions around that age (coinciding with the time it takes the planet to orbit the sun). She started her own art and film companies and found herself doing projects with Givon. In 2008, in her 80s with her health failing, Givon asked the 34-year-old Essers if she’d take on the gallery.

“People say I invested in the gallery, but I didn’t,” Essers says. “I don’t come from money.” She was lent the funds by an unnamed benefactor, “which was incredible that someone would have such faith in a young person who’d never run a gallery before”. Now she is the sole owner.

South Africa’s art market has undergone dramatic shifts over the past decade. When Essers took over the gallery, “South African collectors were primarily buying more Modern work—Irma Sterns and Maggie Laubsers.” There were also, she says, “very few black collectors in the gallery. And I’ve been focused on shifting that. We run five-day art history courses, a lecture series, bring in school groups. It has been around developing new audiences in a new collector base for contemporary art”.

Under Givon, the gallery represented only South African artists, mainly male. “I think there were only three women artists in the stable,” Essers says. In the decade since, she has brought on 34 new artists, many from outside South Africa and 19 of them women. Its roster now includes the New York-based Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, Shirin Neshat (a New York-based Iranian) and Carrie Mae Weems, who is African American, alongside South African artists such as William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Mikhael Subotzky and Candice Breitz.

Alfredo Jaar, Teach Us To Outgrow Our Madness (1995) Courtesy Goodman Gallery

Goodman Gallery has shown at Art Basel since 1982 and Frieze since 2013, and Essers thinks it “critical for us [African galleries] to have more visibility internationally, so that we can make a difference and ensure that other perspectives are written into art history”. However, with the weak and volatile South African currency dropping in value again in the past few months, Essers says it has become very expensive for the gallery to show at international art fairs. It also leaves her with “no choice but to price artists’ work in dollars”.

One has to acknowledge one's privilege as a white person in South Africa

The South African audience, Essers says, is “more grounded” than that of the international fair circuit, but it is “a very small market—literally a handful of big collectors—so we rely heavily on international collectors to sustain ourselves”. Essers struggles with the “astounding disconnect… moving between these worlds, seeing such incredible wealth and such huge poverty, and thinking the world surely can’t continue in this way”.

We speak just before the first FNB Art Joburg (13-15 September), formerly FNB Joburg Art Fair, which has (with some influence from Essers) been sold to its former director, Mandla Sibeko, the first international art fair under black ownership. With racial tensions still running high, is being a white gallery owner a source of unease for Essers? “Definitely. I mean, I’m probably the only female and, being the child of a refugee, I don’t come from a position of total privilege. But, one has to acknowledge one’s privilege as a white person in South Africa, and so it is something I am incredibly conscious of.”

When she took on the gallery, Essers started an unofficial “mentorship programme, for mainly black women, to help them to move into the art world”. Previous mentees include Same Mdluli, who was her personal assistant and is now the chief curator of Standard Bank, and Pulane Kingston, who sits on the board of Art Basel and the Tate’s Africa acquisitions council.

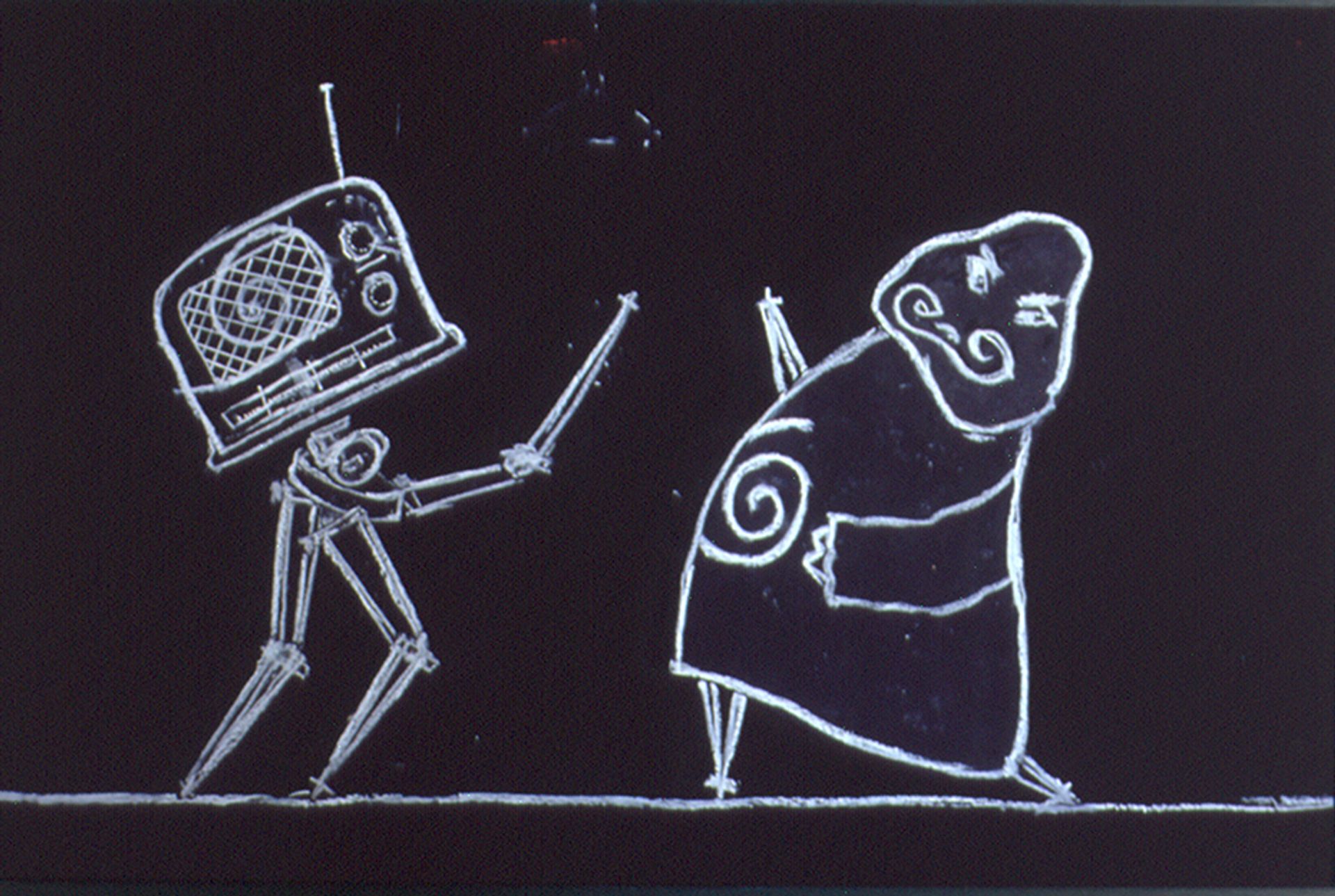

Film still from William Kentridge's, Ubu Tells the Truth (1996-7) Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

Consolidation at the top

Does achieving greater racial parity mean white people will have to relinquish some power in the art world? “I think so. I think it’s something that has to happen all over the world in terms of recognising privilege and shifting economic benefit,” she says.

But economic benefit in the art market seems ever more funnelled into a few (generally white male) hands, and Essers sees “huge consolidation at the top—it’s becoming much more about the bigger galleries”. Although Goodman Gallery now has three locations, Essers still sees it as a relatively small gallery. “It’s challenging. We just need to keep being true to ourselves and collaborate as a counterbalance to [mega-gallery] dominance. The whole system has to shift.”

In that spirit she will give up the London space for one programme slot each year, for free, “to a colleague from the global south who has a similar sensibility to the gallery. The first will probably be Brazilian.”

Still, the poaching of artists—sometimes through cold-calling the studios of rising star artists—is, she says, “more than real” and one reason it “became necessary” to open a London branch of the gallery. “Suddenly many dealers who had never even been to South Africa before are flying in to visit artists,” she says. “Because African contemporary art is such a buzzword, over the past year or two it’s been a very real challenge for us.”

Biography

• Born in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, in 1974. Lives in Johannesburg

• Studied commerce with a major in economics at the University of Kwazulu Natal in Durban

• Worked as a strategic consultant for Accenture and in private equity

• Became an independent curator and film producer, and was co-executive producer of Tsotsi (2005), the first African film to win an Academy Award in 2006

• In 2008, bought the Goodman Gallery