Even as officials plan to conceal a controversial 1930s mural in a school across town, the San Francisco Art Institute has been awarded a $94,000 grant to restore two frescoes of the same vintage that have been covered by whitewash for decades.

The money flows from the Save America’s Treasures program, which is funded by the National Park Service, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The two frescoes were discovered on the walls of the institute in late 2013 by its vice president for operations and facilities, Heather Hickman Holland.

Holland had noticed ghostly traces on the wall of a corridor and then realised that the marks were the outlines of figures and buildings. “You could see the variation in the depth of the plaster,” she said in an interview. “It looked like an image in relief.” Through dogged inspection of the walls and research in the school’s archives, Holland would eventually locate six frescoes altogether that had been whitewashed in the building, all dating from the 1930s.

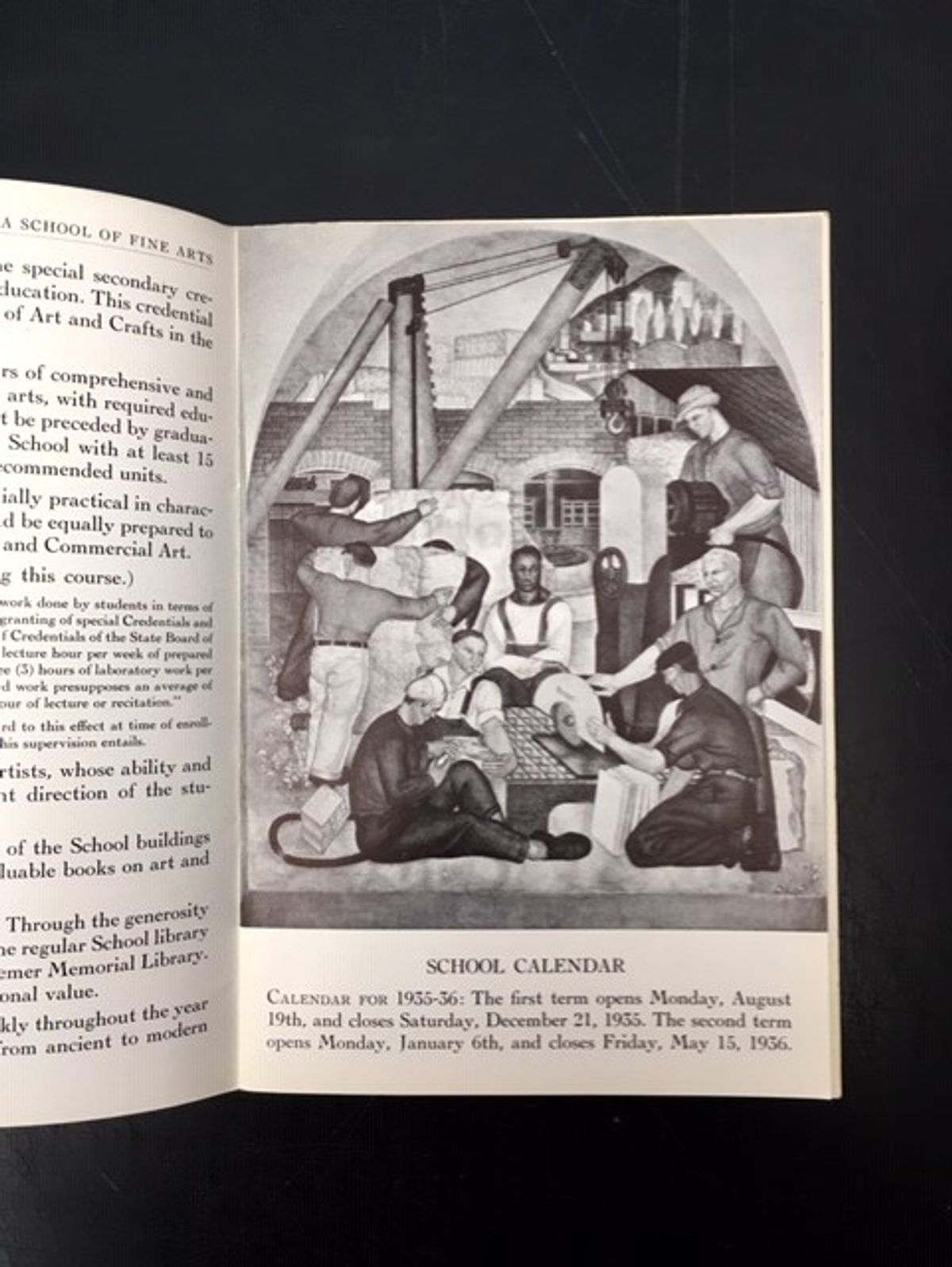

One of the frescoes has been identified through school records: Marble Workers, a 1935 work by Frederick Olmsted Jr., a grand-nephew of the renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Conservators began work on the 10ft high, 9ft wide fresco in late August, removing whitewash and applying in-painting and fills of its vibrant colours. They plan to finish in late October with help from the $94,000 grant and then commence work on a 12-by-12ft high mural that the institute has dubbed Lost Fresco No. 6; its creator, title and subject remain a mystery. Part of the job will involve removing a layer of urethane on No. 6 that yellows the pigments and attracts dirt, Holland says.

Restorers have uncovered the initials of Frederick Olmsted Jr, the artist who painted the 1930s mural Marble Workers at the San Francisco Art Institute Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute

The restoration project contrasts with the fate of a 1930s mural at a local high school, a depiction of George Washington’s life that is to be covered by panels after a narrow vote in August by the San Francisco Board of Education. Critics of the mural object to its depiction of slavery and Native Americans; defenders argue that the work has resounding artistic merit and that its creator was offering a valuable critique of Washington’s flaws.

Among those defenders are faculty members at the San Francisco Art Institute, which played a historic role in promoting the fresco as a Social Realist art form in the 1930s. Teachers in that era invited Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo to San Francisco for Rivera’s first commission in the United States, a mural at the institute titled The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City. The institute became a hive for fresco painting and nurtured a Bay Area muralist movement: the school says that nearly all of the artists who worked on Social Realist frescoes in the city’s landmark 1933 Coit Tower were linked to the school.

Among those artists was the Russian émigré Victor Arnautoff, the artist who painted the controversial mural at George Washington High School. According to Holland, Arnautoff taught at the institute and executed three murals in its library that survive today.

Holland believes that the six murals discovered in 2013 were whitewashed in the mid-1940s but has not yet determined the reason. “We haven’t found any record of them being painted over,” she says. “It could be that Social Realism had fallen out of fashion as artists moved toward Abstract Expressionism.”

The institute’s president, Gordon Knox, who was among the defenders of the high school mural, says that the discovery of the frescoes provides welcome historical context. “Making the ‘lost frescoes’ visible and accessible for the first time since the New Deal era will help further illuminate the stories, experiences and ethos of Bay Area public mural artists at an important time in our collective history,” he said in a statement.

Holland says the spirit of the 1930s muralists survives today. “To have something like this come out and be a surprise just makes people so excited,” she says. “It’s very much an ethos that is alive and thriving.”