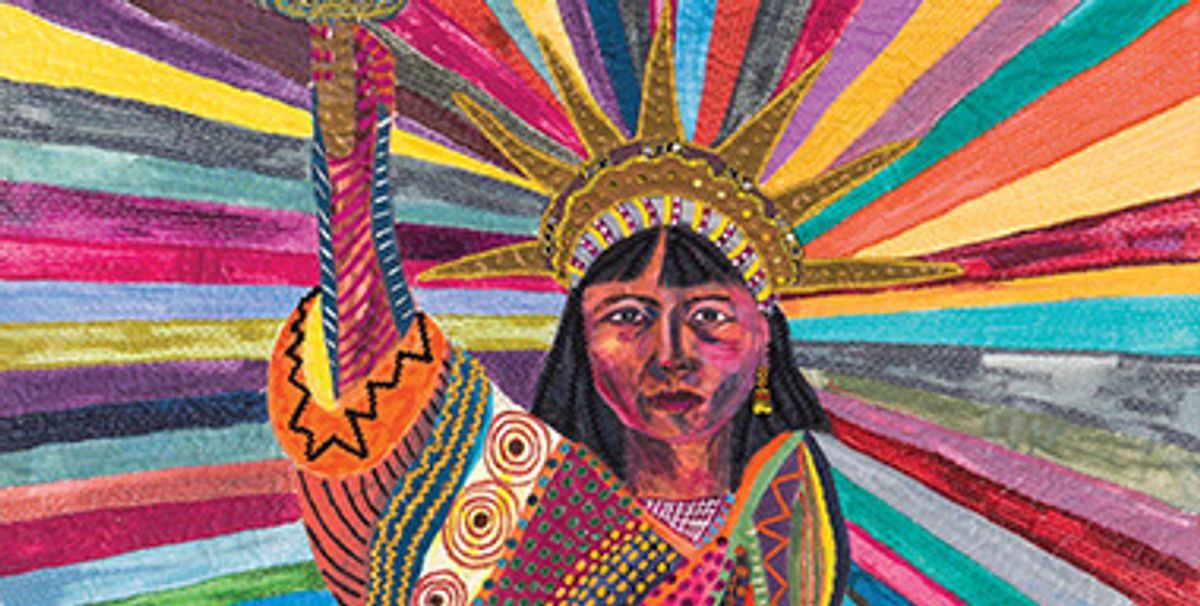

L.A. Liberty (1992) by Pacita Abad depicts the Statue of Liberty as a woman of colour and draws on Abad’s experience of leaving the Philippines for the US. Her work, priced from $60,000 to $75,000, is being shown by Silverlens Galleries from Manila © Estate of Pacita Abad

For the past two years, Frieze London has dedicated a special section of the fair to boundary-pushing female artists. After the sexually explicit feminism of Sex Work in 2017 and the socially engaged art of Social Work in 2018, this year’s theme might seem like a more conventional choice. Woven features eight solo gallery presentations exploring textiles, from knotted biomorphic hemp forms by India’s Mrinalini Mukherjee (brought by Nature Morte) to Bauhaus-inspired geometric compositions in silk, cotton and paper by Madagascar’s Joel Andrianomearisoa (brought by Primae Noctis).

Yet for the section’s curator, Cosmin Costinas, the director of Hong Kong’s Para Site gallery and an enthusiastic collector of textiles, this ancient, undersung medium is replete with political meaning. Textile art has “a very rich history of practice but also a complex history of marginalisation”, he says. “In Europe, it was associated with women and in many colonised spaces it was relegated to the categories of craft or Folk art because it wasn’t perceived to be the language of the Europeans.”

Textiles played a central role in Costinas’s 2018 contemporary art exhibition A Beast, a God, and a Line, which mapped the spread of religious and political ideologies through the Asia-Pacific region, not least Western colonialism. First presented at the Dhaka Art Summit in Bangladesh, the show has travelled to Hong Kong, Myanmar and Warsaw, and will move this winter to Trondheim, Norway, and in 2020 to Chiang Mai in Thailand. In December, Para Site is also hosting an exhibition of decorated bark cloths and weavings from the Polynesian island kingdom of Tonga, curated by Tunakaimanu Fielakepa, the foremost local authority on these practices.

The Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee created biomorphic forms using hemp Courtesy of Nature Morte

Costinas views textiles as “an obvious starting point for a conversation on decolonising aesthetics”—a means of illuminating diverse local contexts and of dismantling the Western divide between ethnography and art. Despite (or perhaps because of) textile art’s appearance of homespun tradition, the medium harbours an activist potential, he argues: “This history of exclusion makes it fertile ground for fighting back.”

Among the more politically charged works in Woven are the trapunto or quilted paintings made in the 1990s by the Filipino artist Pacita Abad (1946-2004), shown by debut exhibitor Silverlens Galleries from Manila at prices ranging from $60,000 to $75,000. The series draws on Abad’s experience of leaving Marcos-era Philippines for San Francisco, as well as her research into the history of US immigration. In L.A. Liberty (1992), she depicted the Statue of Liberty as a woman of colour, in tribute to the Asians, Latin Americans and Africans who followed the millions of Europeans documented at Ellis Island.

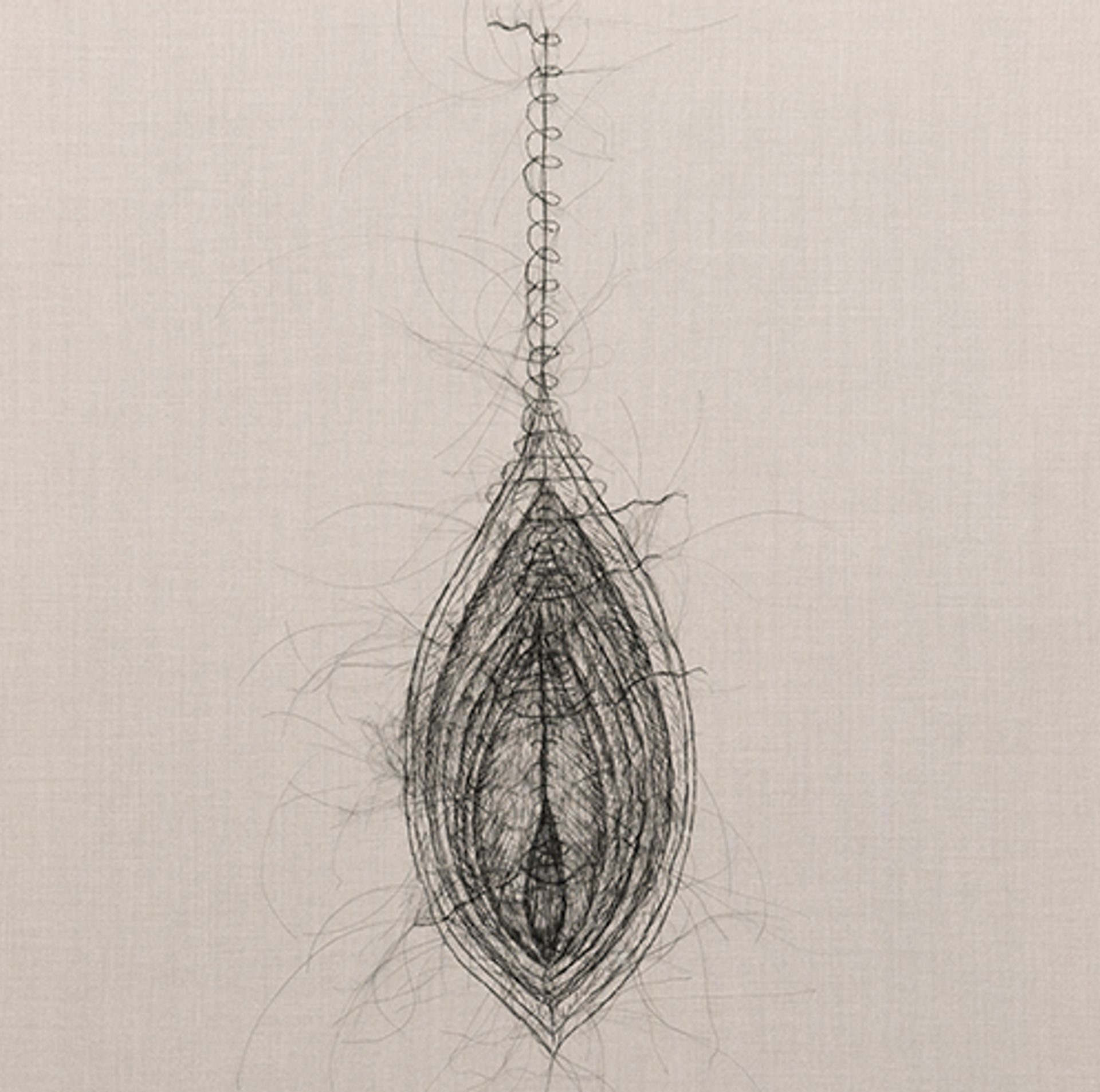

Angela Su incorporates hair in her work because of its powerful cultural symbolism Courtesy the artist and Blindspot Gallery

A more introspective identity politics can be found in the embroideries of José Leonilson, a Brazilian artist who died of an Aids-related illness at the age of 36 in 1993. The works are on show with São Paulo’s Galeria Marilia Razuk. “In the last decade of his life, he confronted issues of identity and desire amid the catastrophe that was affecting the gay world, through these very delicate works,” Costinas says.

The posthumous inclusion of Abad, Leonilson and Mukherjee points to international artists’ engagement with textiles long before the Western art market came knocking. “I’m including different generations to show this is no flash-in-the-pan trend,” Costinas says. “These artists were crucial figures in their contexts.”

Nevertheless, important figures such as Mukherjee and Monika Correa, an Indian weaver who is now in her 80s, worked independently of the gallery system for years. They were “lost between this art-and-craft debate”, says Amrita Jhaveri, the co-founder of Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai, which has brought Correa’s monochromatic cotton and wool tapestries to Frieze. Interest in the artist has grown since the gallery began “showing the work insistently” at fairs internationally, Jhaveri says, with New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art both buying pieces. In view of the “limited supply”—Correa is only able to produce five or six works a year—prices have trebled in the past five years and her works now fetch between $30,000 to $50,000.

According to Lesley Millar, the director of the International Textile Research Centre at the UK’s University for the Creative Arts, textiles have been undervalued in the marketplace because of a dearth of specialist galleries and collectors championing the medium. The university weaving departments and galleries that proliferated across Europe at the height of the Lausanne international tapestry biennial in the 1970s disappeared after it ended in 1995, Millar says.

But in an essay introducing Phaidon’s recently published survey book Vitamin T: Threads and Textiles in Contemporary Art, the Los Angeles-based curator Jenelle Porter counters that: “We are now experiencing another fibre art heyday, yet one very different from the 1960s and 1970s. Our era is post-fibre, medium unspecific.” There has been a generational shift, Porter says, as artists “coming up in their 20s and 30s want to make things and are interested in processes”, and curators are integrating overlooked fibre pioneers such as Sheila Hicks among the painters and sculptors in contemporary art exhibitions. “These artists are interested in making art, period.”

Indeed, two younger artists showing in Woven, Angela Su from Hong Kong (represented by Blindspot Gallery) and Cian Dayrit from the Philippines (with 1335 Mabini), say that textiles are just one aspect of their work and that the message counts for more than the medium. Dayrit, a trained painter who collaborates with a professional embroiderer to appropriate colonial-era maps and images, is drawn to “the idea of challenging the intimacy of fabric to expose painful truths about society at large”.

Su, who investigates the human body through pseudo-scientific drawings, videos, performances and installations, began embroidering with hair for its “tactile quality” and powerful cultural symbolism. Hair “represents the fear and desire projected by men on women’s bodies”, she says, while hair-cutting has been used through history as a tool of oppression. Su’s new series at Frieze London, Sewing together my split mind (2019), produced during the three months of protests in Hong Kong, pictures a woman’s stitched body parts to evoke both “acts of rebellion and the suppression of freedom of speech”.

One artist selected for Woven, Brooklyn-based Chitra Ganesh (with Gallery Wendi Norris), will be represented through mixed-media paintings that include textile elements. The point of the section is “not to reinforce the process of exclusion that textiles are separate from the other art forms and hence perhaps inferior”, Costinas says. “They are entangled in practices—there is one field of aesthetics that should not actually be separated.”

A Huari tunic (around AD800) is priced at $85,000 with Paul Hughes Fine Arts at Frieze Masters © Alain Potignon

Ancient textiles meet the avant-garde at Frieze Masters

The late textile artist Anni Albers dedicated her 1965 book On Weaving not to the Bauhaus where she trained but to “my great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru”. Preserved by the desert climate and excavated around the turn of the 20th century, pre-Columbian textiles became “a spur and a guide” to the masters of the German design school and a host of abstract artists in Europe and the Americas, says the London-based dealer Paul Hughes.

His presentation at Frieze Masters, 2,000 Years of Abstract Arts, highlights this little-known “confluence” by pairing Andean feather pieces dating from AD800-1200 with geometric paintings by Josef Albers’s polymath student Max Bill, as well as works by the South American Modernist Joaquín Torres-García. Returning to Uruguay in the 1930s after years in the US and Europe, Torres-García created a school of Modern art rooted in ancient American symbols.

Artists as diverse as the Alberses, the Surrealist painter Max Ernst and the Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd were devoted collectors of pre-Columbian textiles, Hughes says. Compared with Modern art, there are still relative bargains to be found. Prices at Frieze Masters range from $20,000 for a feather headdress from AD400 to $195,000 for a 2-metre Wari tunic from AD800.