A common refrain at Expo Chicago last week was that the fair “gets busy after six—when people get off work”. It was a saying offered by more than one exhibitor with more than a few minutes to spare when asked how sales were progressing during last Thursday’s VIP hours at the eighth edition of the Windy City art fair, which closed on Sunday.

The observation also proves true in Chicago’s commercial art scene. Although top prices are hard to reach, it is nonetheless growing thanks to an expanding field of collectors buying slower and at lower price points. This is further evidenced by a crop of strong, emerging local dealers and the arrival of Chicago Invitational, a new fair by the New Art Dealers Alliance (Nada) that closed to great acclaim last Saturday.

Taken as a case study, Chicago’s recent boom could prove an optimistic bellwether for the mid-tier marketplace that has frequently been cast as imperilled if not entirely invisible in larger cities.

Sales are notoriously hard to report in Chicago not because they do not occur, but because they do not occur at the rate or within the range at which they take place at larger international fairs like London's imminent Frieze or Art Basel. This can make dealers reticent to share prices since it can by-and-large look like they undersold their artists by comparison.

But in an effort to keep up appearances, these dealers and the often lesser-known artists they represent are frequently elided from the wider market conversation and while, incidentally, perpetuating the predatory nature of some larger galleries that can pick up artists at will with the promise of a higher profile and fatter prices.

“It’s not a gang-busters sales city,” says Heather Hubbs, the executive director of Nada. “But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing happening and more galleries than ever are interested in presenting their programme there,” she adds, noting why she chose Chicago for a new fair after cancelling Nada’s New York event last year—and why she is “resoundingly” looking forward to another edition next year.

Nada says it will return to the Chicago Athletic Association for another edition of Chicago Invitational next year. Courtesy of Nada

Hubbs’s assessment points to a demographic of aspirational collectors that is often misunderstood and potentially undervalued, although which Chicago has consistently served with smaller but weighty fairs like Expo that puts many of the city’s hometown hero galleries on great display—Rhona Hoffman, Monique Meloche and newcomer Mariane Ibrahim, to name a few—while also attracting major blue chip dealers regularly if not always consistently.

Marianne Goodman, Hauser & Wirth and Lisson gallery were among some of the new additions this year, although previous participants such as Léy Gorvy opted out of this edition.

That does not worry Expo director Tony Karman, however, who acknowledges “fairtigue” is a codified affliction at this point. “I’m aware of 30 to 40 dealers who have put [the fair] on a two-year rotation. Great. There’s space for them when they can do it,” he says. What he prides the Expo on is staying “nimble” at around 130 exhibitors while still making Chicago a place where global dealers “can come and do well”.

Playing the numbers game

"Doing well" is essentially an issue of scale. A focus on top-level sales more often than not overlooks the hustle that is happening. “It isn’t an urgent marketplace for art, it’s about making good contacts for things that could happen in the future,” says Aron Gent of Chicago’s Document gallery, which represents artists such as Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Andrew Norman Wilson and Laura Letinsky.

Gent participated in Chicago Invitational, which ultimately helped contextualise Expo—which is always vying for a higher international profile—as a fair of a certain stature, if not the global-must-see stature it is working toward. “I think different types of art require different types of conversations and that appropriately scaled venues reinforce those conversations. I’m happy Nada saw that and decided to launch a fair in Chicago,” he says.

When asked to summarise his experience of Nada’s event, Gent says “I expected a little more traffic but the fair did look better than I thought it would”, noting the fair’s venue at the historic Chicago Athletic Association. He also adds that “we did better than I thought [we would]”, preselling two works, selling five “low-to-medium” priced works the opening day and then three more works onsite at the gallery during the run of the fair.

Crowds at Chicago Invitational were thinner than expected but Gent says his gallery still did "better than we thought we would" when it came to sales. Courtesy of Nada

At Expo, sales were mixed, especially for non-locals. Hauser & Wirth’s Marc Payot says that all ten of Lorna Simpson’s works on the stand (priced between $295,000-$425,000 each) had been placed by the end of the VIP day, including acquisitions by five museums. This kind of turnover proves a rarity, even if commonplace at a fair like Frieze or even to an extent at similar-sized metropolitan fairs like New York’s Armory Show.

New York-based Kasmin, situated at the highly visible booth at the entrance to Expo, brought a wide selection of works from artists spanning their programme available for between $30,000 and $1m. Over the course of the fair, the team sold four works by Robert Indiana, Bosco Sodi, Elliott Puckette, and James Nares (who currently has a retrospective on show an hour away at Milwaukee Art Museum). One of the most expensive works on the stand, however, a large cut-out sculpture of a cowboy by Alex Katz, failed to sell at the fair but got swept up in New York once it returned.

A handful of dealers expressed dismay at the amount of work they were toting back to their respective galleries by Sunday night, regardless of price. But many more reported plenty of works offered for under $30,000 that were more easily placed. It comes down, more often than not, to knowing how to court the city’s collectors.

Henry, Chicago’s most eligible bachelor

In an era when the international art market is by and large defined by big galleries selling works by big artists for increasingly bigger prices to “the big” collectors who travel to all the big fairs, the so-called “city of big shoulders” is buoyed by mid-tier collectors—intellectual and engaged art buyers that rely on their salaries to sustain their lifestyle and hobbies. The working rich are hard to place within the 21st-century art boom narrative that trains its eye on the ultra-wealthy.

There is a financial industry term for these types: “HENRYs”, an acronym for High Earners, Not Rich Yet, first coined by Fortune Magazine to describe those with above-average salaries, but who might not have much left after paying taxes, student loan debt and mortgages, etc. This new class of collectors are not the high-net-worth individuals who benefit from generational wealth or are at least relieved from the drudgery of day-to-day work by virtue of their high-yield investments, freeing them up to pursue passion assets the world over (yet these types certainly do exist in Chicago).

It is also essential to note that these collectors are not exactly middle-class. According to 2016 US census data, around a quarter of households in the city of Chicago earned more than $100,000 a year in 2016, slightly above the middle-income for Illinois of about $88,000, but short of the upper-income’s strata of $187,000. Henrys are generally classified as earners making somewhere between $250,000 and $500,000.

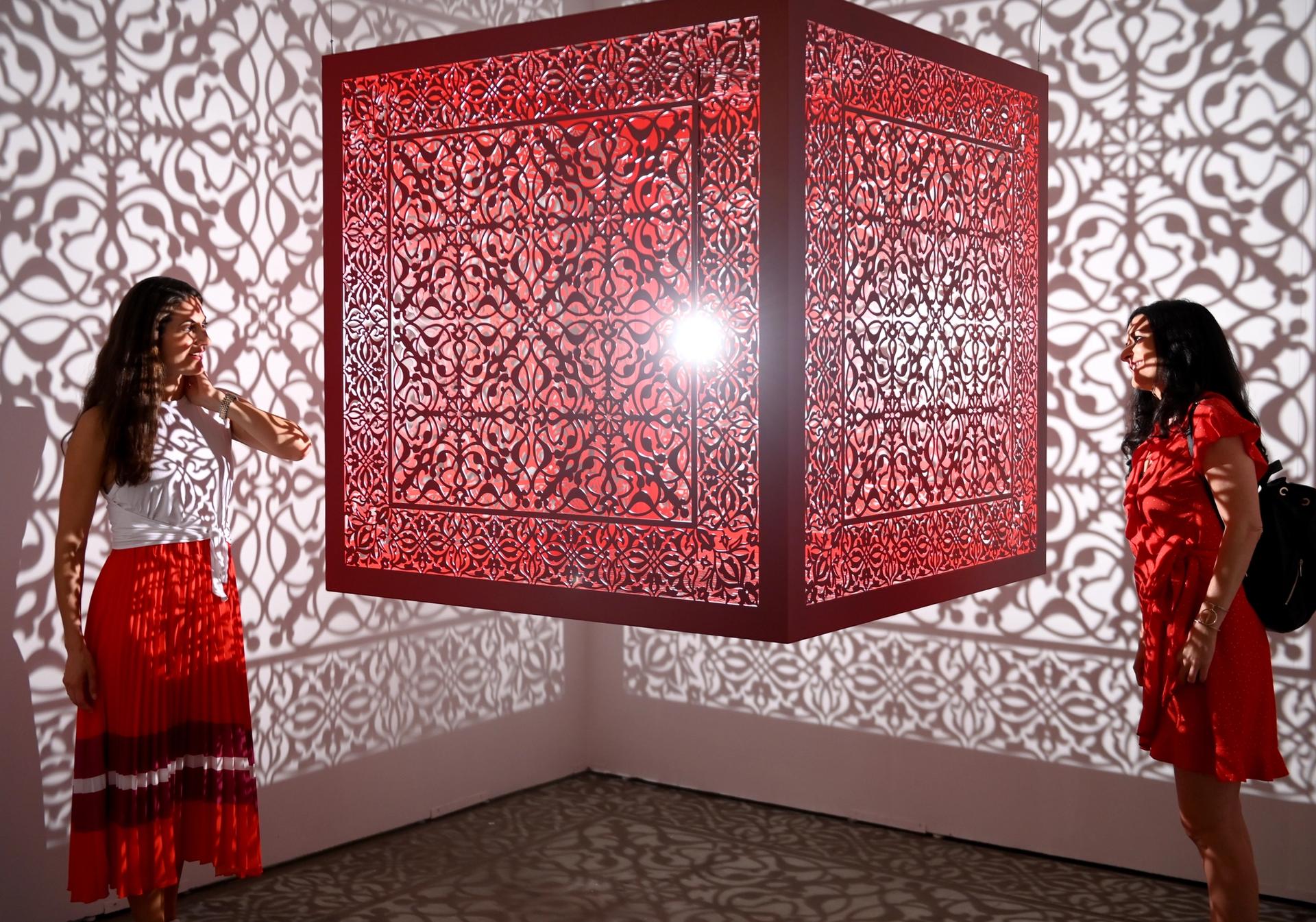

Chicago boasts a young collector base buying works of art under $50,000. Photo by Justin Barbin, Courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery (New York, Singapore, Hong Kong) and Expo Chicago.

These individuals benefit from cushy jobs, of which the Windy City has many, coupled with a lower cost of living. Indeed, Chicago has flourished further even since the 2016 census report, at least superficially if you look to the shiny high rises and condos proliferating along the river coupled with the international companies that have set up shop there: telecom giant Motorola Solutions (2016); the world’s third largest spirits company, Beam Suntory (2017) and GE Healthcare (2017) have all relocated their headquarters to the city’s downtown, bringing with them ample jobs for younger to middle-aged white-collar workers.

“There is a large group of people here who are younger, buying art at the sub-$50,000 range,” says a director at one of the city’s prominent emerging galleries, who exhibited at Chicago Invitational, when asked what kind of deals they typically make on any given day, fair or no fair. These collectors take time to cultivate and take their time buying, likely because purchasing a work of art represents a significant investment of their expendable income. “They have careers and are working full time,” the director says, but they spend their free time “diligently researching the artists they want in their collection”. They are not buying art to flaunt their wealth, but to express an ideology of inclusion.

Leaning into learning

The element of education is key to understanding what Chicago as a marketplace has done very well. The curatorial programming and outreach endemic to Expo, developed by Stephanie Cristello and Mia Khimm, is arguably the fair’s greatest accomplishment thus far. Karman also unfailingly points to the city’s long-respected museums that he says prove a continual draw for collectors and curators alike.

This year, however, the major museums were largely offline during the run of the fair, with many galleries closed for installation at the Art Institute of Chicago and a thirst-trap of a show dedicated to fashion designer Virgil Abloh at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The Chicago Architecture Biennial aside, the lack of curatorial depth on view underscored how flooded the commercial side of the city’s art scene was with intellectual rigour and how to leverage that to bring in more collectors—and revenue, of course.

It is a long-game Karman is playing. “Chicago has a strong collector base, generationally speaking,” he says. Indeed, the city is known for figures like Larry and Marilyn Fields, Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson, and Penny Pritzker and Bryan Traubert, all of whom have strong ties with the museums there, frequently donating works or funds and sitting on boards. “But there’s been a real absence of that level of engagement in the past couple of decades,” Karman says. It is a problem that permeates US arts philanthropy across the board, regardless of place. What Expo has strived to do is to create a new collector class, “feeding the ecosystem” in order to sustain its galleries and, ultimately, its museums, according to Karman.

Arternativ helped Expo bring in international collectors this year. Photo by Daniel Boczarski, courtesy of Expo Chicago

That means globalising the last “Great American City,” as Chicago is often called. Indeed, this year was billed as one of the most international editions of Expo to date thanks to a record number of collectors and curators from abroad. Of the roughly 120 collectors listed on the fair’s “official” VIP list, around 10% of them were international collectors brought by Eva Ruiz, the founder of the Madrid-based firm Arternativ, an agency that works with mid-size art fairs to bring in more global buyers. Her existing clients include Mexico City’s ZonaMaco and the Armory Show, among others.

“Many smaller fairs just don’t have the internal infrastructure to identify and attract international collectors that the big ones do,” she says. Ruiz assists them by matching collectors from further afield, enticing them with a few nights of free accommodation and a specialised itinerary that sees them sashayed from studio visits to dinners.

The most difficult part is matching the local marketplace to the right international collector base, according to Ruiz. “Everyone always wants me to bring them the Rubells,” she laughs, but she says instead you have to bring the people who are buying at the same level as the galleries there are showing.

Ruiz organised a special visit to Chicago-based artist Nick Cave's studio for her coterie of collectors. Work by Nick Cave at Expo. Photo by Kevin Serna, Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery (New York) and Expo Chicago

To that end she brought a group of mainly European collectors that essentially mirrored the Chicago collector base: those with a keen desire to spend time learning more about contemporary US and Latin American art and interested in buying works “mostly between $8,000 and $30,000”.

Of her essentially B2B art fair service, Ruiz says: “This isn’t necessarily the sexiest work. It’s about sustaining the market. The auto industry does not revolve around luxury cars, it runs on Fords and Fiats.” While the art world forgets that sometimes, Chicago is remaining rooted in its industrial past as it looks to the future—even as recession clouds gather, making the outlook hazy.

“There is so much potential here, real art being made,” Ruiz says. “For these collectors, it was an easy sell.”