One of Lebanon’s best-known women artists, Huguette Caland, died yesterday in Beirut aged 88. She was famed for her bright abstract paintings, erotic line drawings, and her Middle Eastern-inspired fashion designs. “It is with great sorrow that we announce the passing of one of our greatest artists, Huguette El Khoury Caland, a beautiful soul, and a lover of life and freedom,” Galerie Janine Rubeiz, the artist's representing gallery, said in a statement. Her most recent exhibition, a retrospective at Tate St Ives, closed on 1 September.

While her art is held in high esteem, her extraordinary life has also been the subject of much intrigue. Born in Beirut in 1931, she was the daughter of Bechara El Khoury, the first president of post-independence Lebanon from 1943. While she took her first painting lessons at the age of 16 with the Italian artist Fernando Manetti, it was not until her father passed away in 1964 that Caland decided to pursue art as a career. That year, she enrolled in a fine art course at the American University in Beirut. By this point, Caland had married Paul Caland (the nephew of one of her father’s political rivals), had children, and taken a lover called Mustafa (who featured in many of her works). In 1970, she decided to leave her life in Lebanon behind and move to Paris to build a career as an artist. “Art is not a part of my life; it is my whole life,” she later said, explaining her decision.

In Paris she was “liberated from social obligations [and] she was able to blossom and meet many contemporary artists”, according to the gallery’s website. Her distinctive work combines elements of her Middle Eastern heritage, such as Islamic pattern, with the abstraction and Minimalism that she she was exposed to in Europe. For example, while in Paris, she collaborated with the designer Pierre Cardin on designs for the “Nour” line of kaftans, combining traditional Arab dress with revealing prints of body parts.

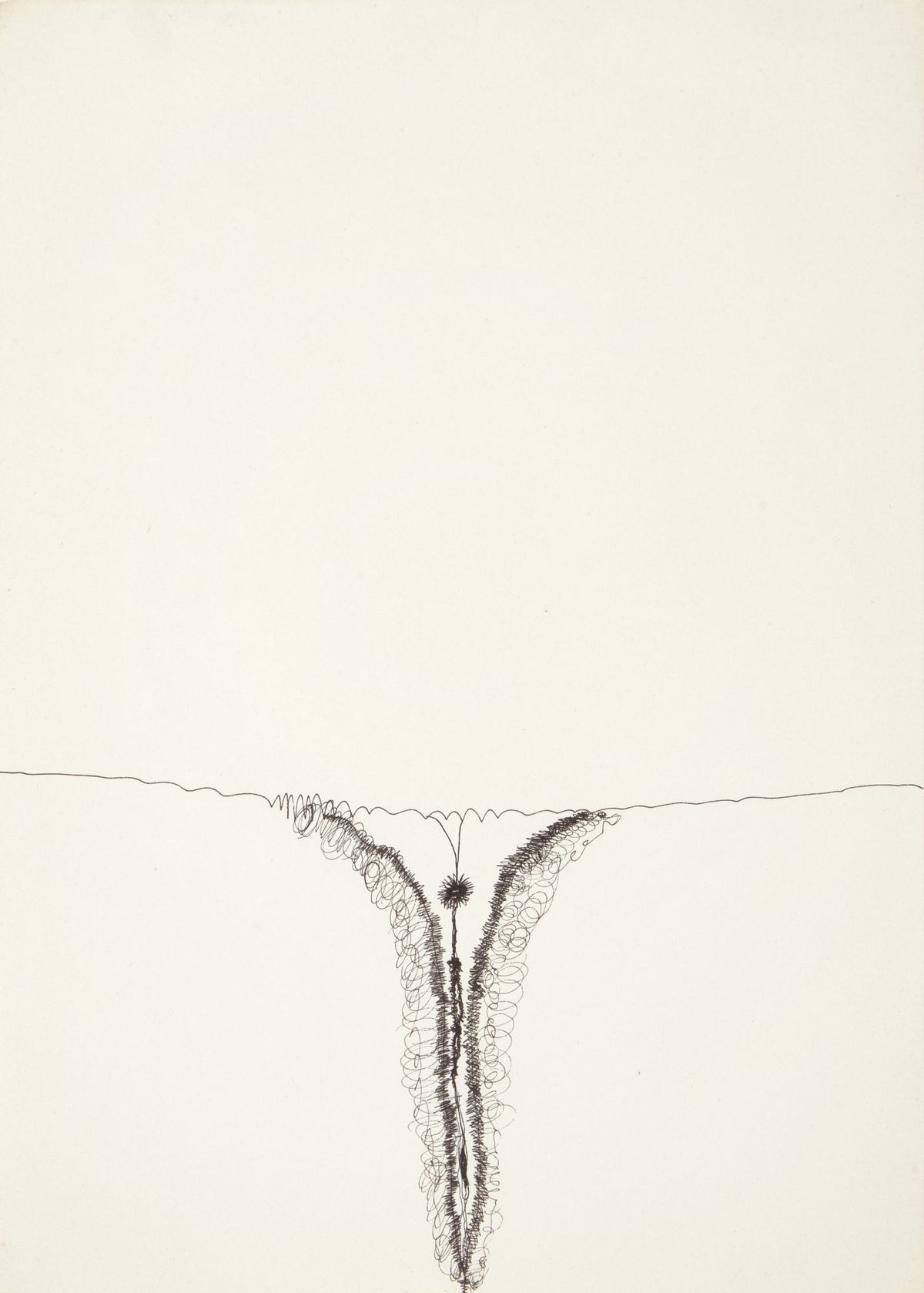

Her interest in the female body was ubiquitous in her work. In her 1970 series Body Parts she offered “liberated depictions of the female physique at a time when the prevailing fashion was all about being tall and thin,” according to the Tate website. “Her magnified views of bodies range from more recognisable forms to ones that are almost entirely abstract, yet still suggestive. Body parts are transformed into bold fields of colour and curving forms which often resemble rolling landscapes or crevices.” Her gallery describes her exploration of sexuality and voluptuousness as “clearly ahead of her own time”.

The “Nour” kaftans that Caland made in collaboration with the designer Pierre Cardin, on show at Tate St Ives © Tate

In 1987, following the death of her partner, the Romanian sculptor George Apostu, Caland moved to California where she established a studio. In 2013, she returned to Beirut to care for her ill husband and remained there until her death.

While famous in Lebanon and the region for decades, her work only attracted major Western attention in 2016 when she showed at the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A. biennial. Since then she participated in the 57th Venice Biennale Viva Arte Viva (2017) and had a solo show at the Institute for Arab and Islamic Art in New York (2018). In addition to the Tate St Ives show, Caland’s work was also exhibited in the Sharjah Biennial this year. Her paintings, drawings and designs can be found in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou and La Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; the British Museum in London and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others.

Many artists, curators and friends have posted tributes on social media. “Although her father was the founding president of Lebanon, she chartered her own path in life as a designer and artist. Her work is today amongst the most coveted of any Middle Eastern artist,” posted Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, an Emirati lecturer in Middle Eastern art and politics and the founder of Sharjah’s Barjeel Art Foundation. “How wonderful that she lived to see her first UK solo exhibition at Tate St Ives, and how privileged we feel to have seen it,” posted the arts initiative Edge of Arabia on Instagram. The curator and co-founder of the Ruya Foundation, Tamara Chalabi, described her as “a role model for how to be free”.

“Huguette Khoury Caland was a force in the Arab and global art world to be reckoned with,” says Basel Dalloul, a Lebanese collector and the managing director of the Dalloul Art Foundation. “She transcended the politics and social norms of Lebanon and the region. She was and always will be a beacon of freedom and hope for generations to follow. Her amazing attitude and beautiful smile will be sorely missed.”

Tate described its exhibition of Caland’s work as “express[ing] the pursuit of exuberance and joy that has characterised much of Caland’s art and life”. She herself once said that she loved every minute of life: “I squeeze it like an orange and eat the peel, because I don’t want to miss a thing.”