If one were asked to name a Midwestern metropolis known for its urban architecture, Chicago would almost immediately spring to mind. The Windy City, however, is not the first place in Illinois to fit that description. Just 300 miles south on the banks of the Mississippi River—and about 1,000 years in the past—the bustling Native American city of Cahokia once boasted the largest population of any settlement north of Mexico. It was also celebrated for its intricately designed earthen structures, which numbered nearly 200 and were plotted on a city grid aligned with the sun.

The largest of a network of mound-shaped complexes stretching from Ohio to Missouri, created by the Indigenous peoples who inhabited the area, Cahokia reached its peak around AD1100. While the earth works still stand, the makers have been displaced and their history obscured. The Chicago-based artist Santiago X, however, is reviving Indigenous mound-building with two public installations along the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers as part of this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial, which opens on Indigenous Peoples’ Day (14 October). It marks the first time that effigy earthworks have been constructed by Native Americans in North America since the founding of the US.

During the 19th century, white settlers migrating west largely buried the truth about the Midwest’s mound cities, often mythologising them by crediting their creation to distant civilisations—sometimes even aliens. At the same time, Indigenous people were being forcibly removed by the US Federal Government to reservations, often in other states, further distancing them from their ancestral lands and architectural heritage.

A registered member of the Coushatta tribe of Louisiana (Koasati) and the Chamorro people of Guam (Hacha’maori), Santiago X practises across land art, architecture and new media; he is also part of the hip-hop duo Santiago x The Natural. Billing himself as an Indigenous Futurist, he sees art as an essential tool in the reclamation of Native American tradition and identity after the systematic erasure of Indigenous peoples by white European colonialists. He speaks with The Art Newspaper about reviving architectural traditions and re-envisioning contemporary Native identity.

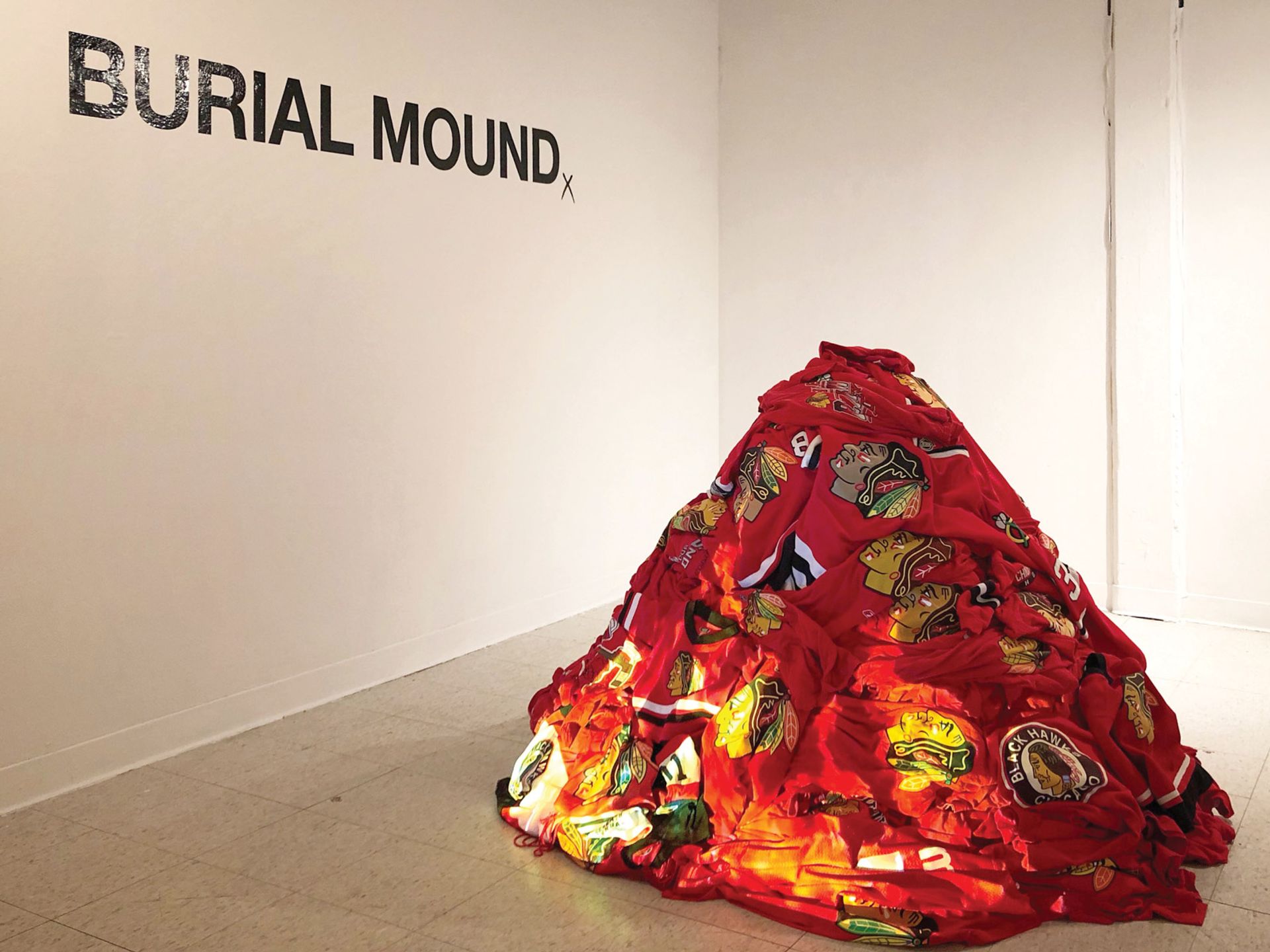

Burial Mound (2019), top, one of Santiago X’s installations based on ceremonially burning Chicago Blackhawks hockey jerseys Courtesy University of Illinois - Chicago

The Art Newspaper: What does it mean for you to reclaim the tradition of mound building within the context of a contemporary architecture biennial in Chicago?

santiago x: I’m pretty excited about this opportunity in general since there have been no earthworks like this constructed by Native Americans since the US was created. These structures—effigy mounds in particular—are certain typologies of mounds that were long built by Indigenous peoples and nearly every state along the Mississippi River has some that are residually visible. These were destinations and, similarly, the works I’m creating are destinations of contemplation—a space to think about those that we displace with any kind of urban development billed as “progress”. This is also a way of restoring Indigenous place-making and will function as a reminder that the architectural world in America predates what we see now. And, moreover, the structures that we build today will have a post-industrial life—we need to think about reciprocity with the earth as we build on it.

Great Serpent effigy mound, near Locust Grove, Ohio Photo by Granger/Shutterstock

There are several symbols and sites of particular meaning within the history of mound effigies. Can you explain their significance?

Perhaps one of the most recognisable symbols is a serpent. The Great Serpent mound in Ohio is particularly well known and there’s actually another one in the Chicago area. These were important historical portage sites [where boats or cargo were carried between bodies of water]. For Indigenous peoples, the serpent is the threshold of endangerment and prosperity. It can be deadly but it can also bring new life, represented through the shedding of its skin. You can often see an egg in the mouth of some of the snake symbols, which is a nod to the serpent’s generative and destructive power. This symbology has contemporary applications as well—the pipeline at Standing Rock is actually called the Black Snake by the Indigenous peoples in the area. I am building a serpent effigy on which there will be digital projection of scales to make it look like it is moving. It’s not nostalgia, or replication; it’s about being able to innovate on our own land again, which gets to the heart of what it means to be an Indigenous Futurist.

There is another, indoor, component to your work for the biennial, which will be installed in the Neo-Classical Chicago Cultural Center downtown. What kind of form will this take and how will it correspond with the earthworks?

From an architectural standpoint, I’m tired of fake European buildings in Native America. They have displaced people and ecosystems to glorify colonisers. In the Chicago Cultural Center, I’ll be using the same architectural language of Indigenous mounds but on a smaller scale. I see an opportunity to break the plane by bringing the land inside this disenfranchising built environment—I’m trying to bend the walls a little and make you think you’re on the earth when you’re really on the fourth floor.

Santiago X's The Return, Light and Sound (2018). Installed at Ars Electronica Festival 2018. Linz, Austria © www.ottosaxinger.at

Earthen mounds are not the first mounds you have made, though, right?

I also work with streetwear a lot and an outgrowth of that has been an ongoing project of creating burial mounds made out of Chicago Blackhawks jerseys. The hockey team’s mascot is the head of a Native American on a red background, as if it’s a pool of blood—it appropriates Native American culture and valourises violence. I’ve created these jersey mounds at a couple of different places around the city; I then destroy them by doing a ceremonial burning. At first, it started with a performance I did as part of New Monuments for New Cities [the inaugural project of the High Line Network Joint Art Initiative on the city’s public biking and walking trail known as the 606]. I laid a bunch of Blackhawks paraphernalia out and asked passers-by to put them in trash cans in an act of solidarity.

I wanted to make people more aware of what they’re supporting when they’re supporting their hometown team; we need to generate more dialogue around it. I started the mounds project by asking people to donate their Blackhawks jerseys to be destroyed. My daughters and I would also go around to the area thrift stores to buy up all of the jerseys we could find and soon people were donating money to purchase them.

Using Native American imagery as logos or mascots for sports teams has been a controversial topic in the US for many years. Did you receive any backlash against the destruction of the jerseys?

Most people were supportive. But being a contemporary Indigenous artist in America, resistance is a daily thing. It takes a toll. Indigenous artists that have any kind of public exposure, are dealing with hostility and deep-seated sentiments all the time. What we do is ultimately a labour of love. Hopefully we can make a more harmonious world for all—that is the crux of our belief system as indigeneity is a kind perpetuity with the earth and the cosmos. I try to find that through art, and I do it for the empowerment and celebration of my people. Whoever shows up to be allies for us and our longevity and for a healthier relationship to the earth, it’s for them too.