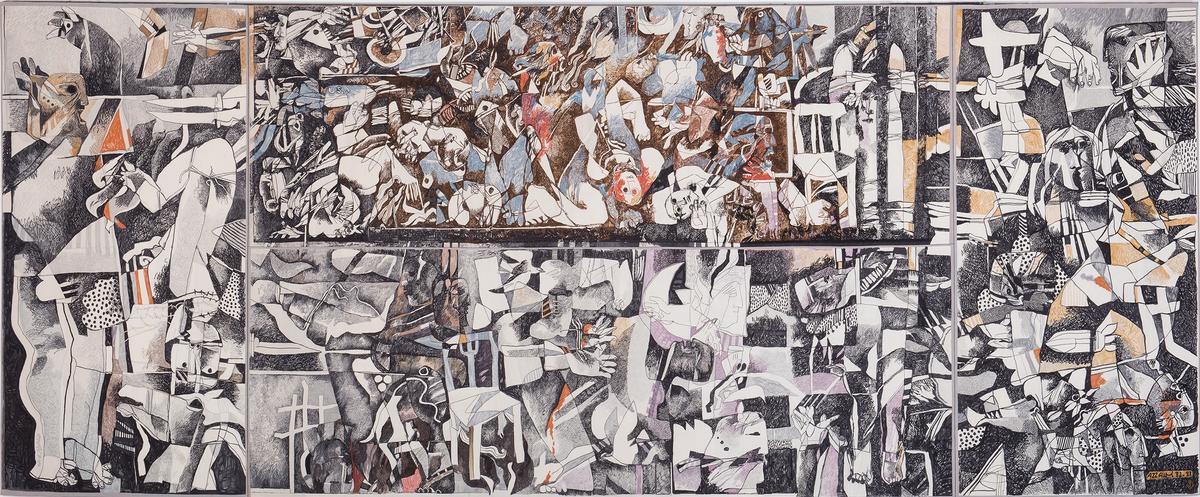

The Tate’s famous colossal work known as the “the Guernica of the Arabs” has been recreated in tapestry form. The Lebanese art patron Ramzi Dalloul commissioned the woven recreation of Dia al-Azzawi’s Sabra and Shatila Massacre (1982-83) so that more people can see the masterpiece that currently resides in the collection of London’s Tate. It took more than 30 craftspeople at Spain’s Real Fabrica De Tapices four years to complete.

The original ink-and-crayon drawing, which measures 3 metres by 7.5 metres, was created by the Iraqi artist in response to the slaughter of hundreds of Palestinians by Lebanese Christian militia groups in areas under the control of the Israeli military. “It archives a violent time in Lebanon’s history, a history during which every side involved committed atrocities,” says Basel Dalloul, the managing director of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

The team in Spain weaving the colossal work Photo: Nacho Perex Ortiz and Real Fabrica de Tapices

The idea to copy the work came soon after the Tate acquired Sabra and Shatila Massacre in 2012. “The original work was unfortunately drawn on acidic paper which turns yellow with time and light exposure,” Basel Dalloul says. “It is very well conserved at the Tate Modern, but only exposed and shown three months out of the year. Travelling the original is thus difficult,” he adds.

Dalloul’s father, Ramzi, convinced Dia Al Azzawi to allow him to weave the work, in the interest of conserving the work for centuries, in the same way that Picasso gave Nelson Rockefeller permission to weave Guernica (1937), which now hangs in front of the Security Council chamber at the United Nations in New York. The Tate has collaborated on the tapestry project, allowing technicians employed by Ramzi Dalloul to take extensive high-resolution photographs of the drawing to use as guides. Al-Azzawi has also been involved in the project.

A detail of the weaving for Sabra and Shatila Massacre tapestry Photo: Nacho Perex Ortiz and Real Fabrica de Tapices

The tapestry is now part of the vast collection of the Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation collection, and Basel Dalloul plans first to exhibit it in Beirut. However, the main point of the recreation is that it will now be possible to send it for exhibitions abroad. “We have a rigorous plan to tour the piece around the world,” Basel says. He also hopes that one day the tapestry will be shown alongside the original at the Tate Modern. “Anything is possible and yes, I would very much like to see both pieces hanging side by side,” he adds.

But Basel stresses that there is a bigger mission behind the reproduction of Sabra and Shatila Massacre. “The best way to not repeat history, is to not forget it and art is an archive of history,” he says. “It’s important to us that this work is seen, without singling out any party or parties involved. We want peace in Lebanon and peace in the region.”