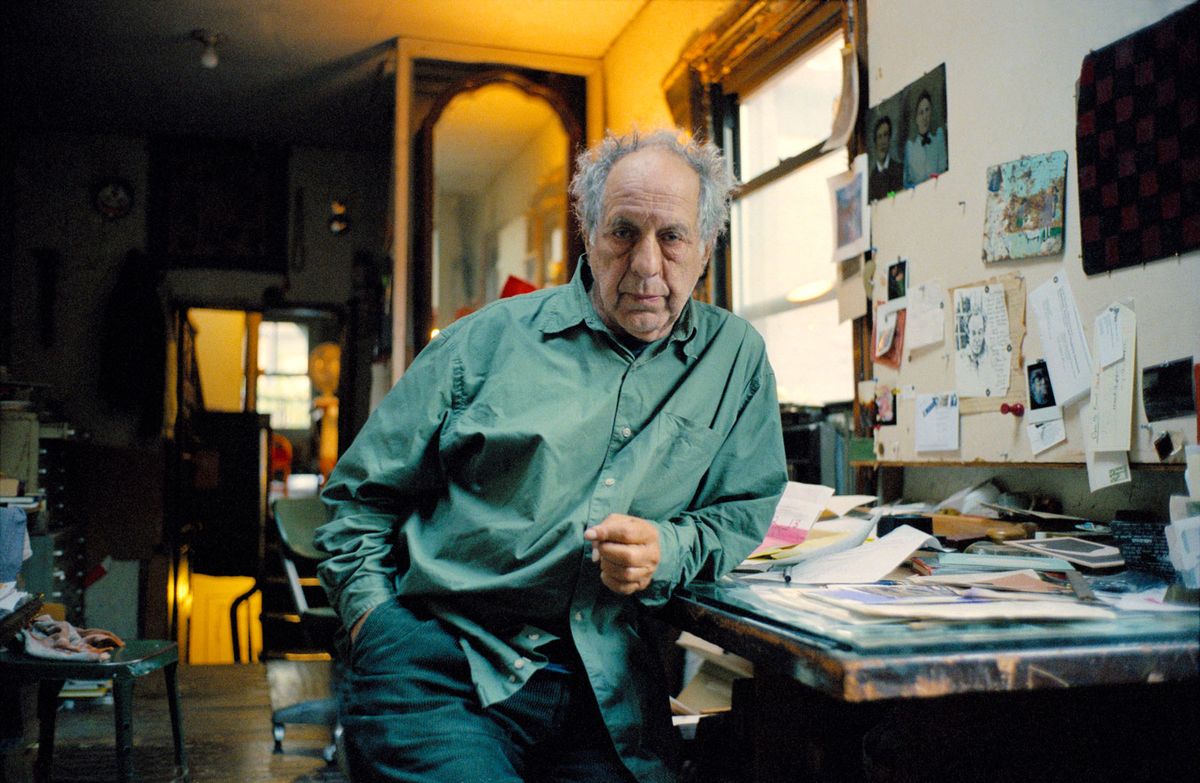

Robert Frank (1924-2019), a Swiss-born Jewish immigrant who published The Americans, the hugely influential ensemble of photographs of his adoptive compatriots, died yesterday in Nova Scotia, another land that Frank documented. He was 94.

Frank’s impact on photography was as broad as it was inescapable. “If there was a sea of photography, he was the anchor that everybody wanted to tether to,” said the photographer and filmmaker Stephen Wilkes, “he was an innovator, he had such a vision. I, myself, I used the carry around The Americans like it was a Bible.”

In films in the 1960s and later where he turned the camera on himself, Frank’s work was deeply personal as he reflected on the loss of his two children and on the psychic and physical pains of getting old. “A natural disaster…. swollen toes, nails falling out, gum disease, itching, irregular heartbeat,” he said in his film True Story (2004).

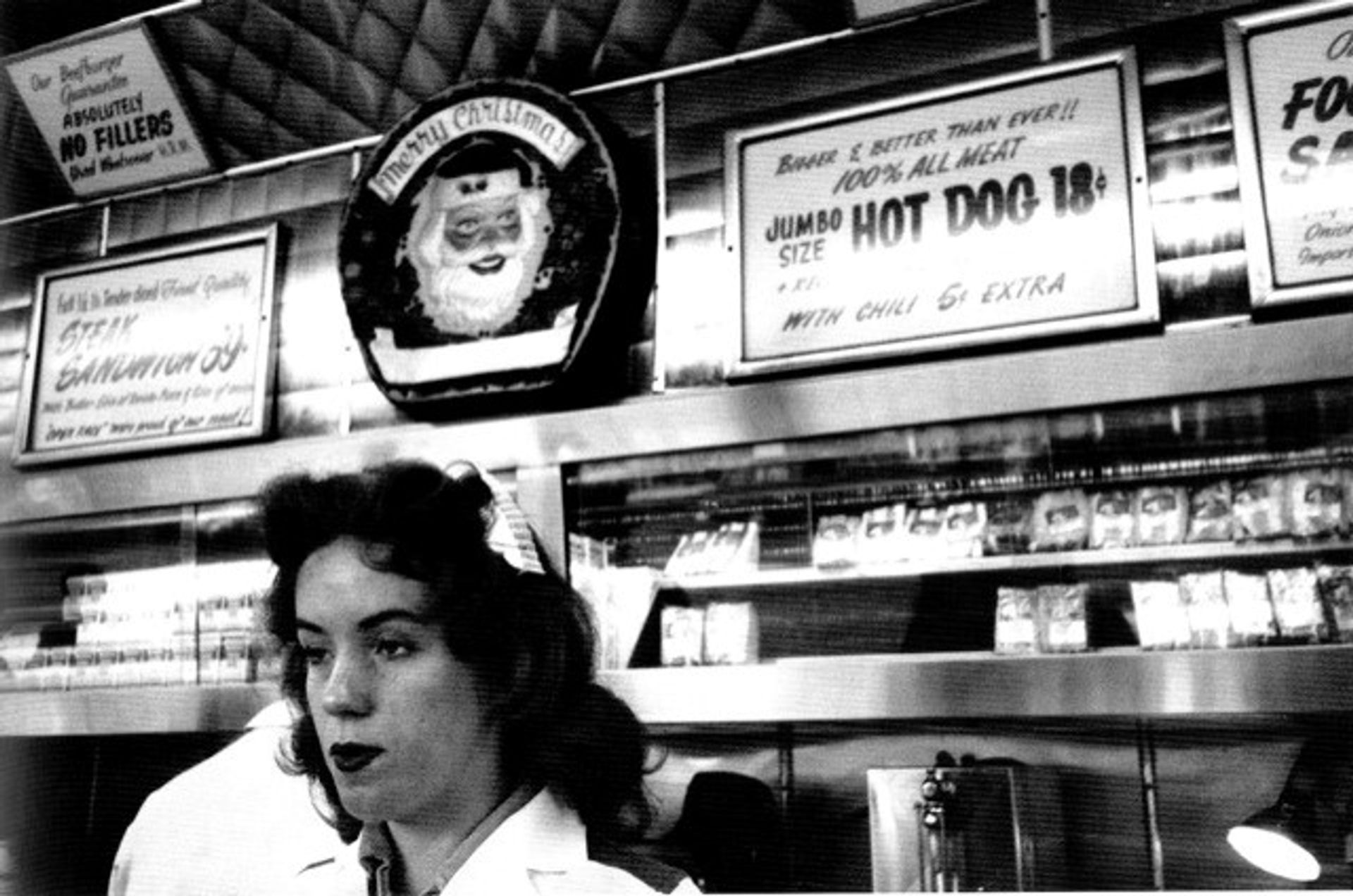

Robert Frank, Ranch Market – Hollywood (1956) from the series The Americans © Robert Frank from The Americans, courtesy Pace/MacGill

The improvised documentary Pull My Daisy (1959) also showed Frank to be a deft observer and documenter of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and other Beat Poets in New York. Frank gravitated to those circles after he arrived in the US in 1947 and began working at Harper’s Bazaar.

Soon he traveled beyond New York. The Americans were images from trips that Frank made across and around the US for two years, starting in 1955. The book was published first in France in 1958, then in the US—both times without text. Kerouac, a friend whose On the Road preceded The Americans, later wrote an introduction.

The US was "a country that I didn’t really know. I was just there for a couple of years,” Frank reflected decades later.

When The Americans was published, “most of the people who commented on it at the time thought that it was unfair, that the country was presented in a negative way—which I guess it was,” said fellow photographer Elliott Erwitt.

“There’s the least bullshit in photography as practiced by Robert Frank,” Erwitt noted.

In the recently released 2004 documentary, Leaving Home Coming Home (which showed briefly at film festivals in 2005 until Frank blocked its distribution, only to change his mind a decade later), Frank recalled that “the reaction surprised me. People thought it was an anti-American story. It took ten years till they changed.”

Frank chose not to follow The Americans with a sequel. “You have to make a tremendous effort not to repeat,” he says in the 2004 documentary.

Making films in the 1960s, Frank also provided photographs for the Rolling Stones’ 1972 album, Exile on Main St., and followed that with Cocksucker Blues, a commissioned documentary of the band’s 1972 US tour. Raw footage of the group backstage, including scenes with nude groupies, proved too frank for the Rolling Stones, who placed severe restrictions on showing or duplicating it (still in effect at four screenings a year).

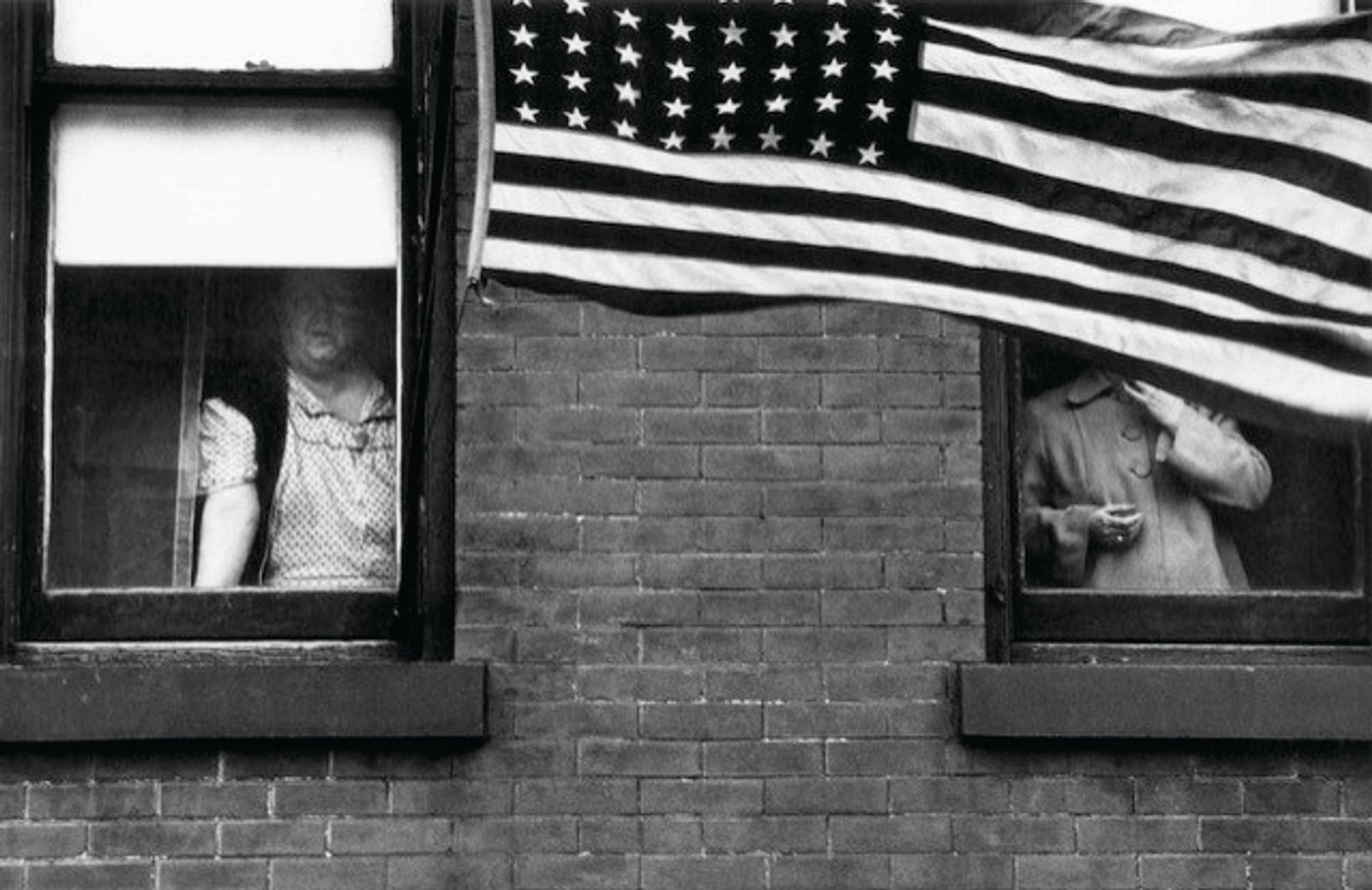

Robert Frank, Parade - Hoboken, New Jersey (1955) from the series The Americans © Robert Frank from The Americans, courtesy Pace/MacGill

During that time, Frank also worked in austere windswept Nova Scotia. Films that he narrated there explored his personal losses. Frank’s daughter, Andrea, died at 20 in a plane crash in Guatemala in 1974. His son, Pablo (named for Pablo Casals), struggled with mental illness and committed suicide at 44 in 1994.

“Life is hard, but it goes on,” he says, standing on a New York City street in the 2004 documentary, “the traffic takes it away like the waves in the ocean.”

Thinking back at his still photography, he spoke of two now-iconic pictures from The Americans taken in 1955—people walking along a street in New Orleans and a flag blowing across a window in Hoboken, New Jersey—and called those images “accidents.”

“If you have some brain and some feeling for people, you’re going to be a good photographer,” he said. “I choose a reality that exists, and maybe I’m careful that in my framing it is preserved.”