Four hundred years after the arrival of the earliest documented Africans in the American colonies, Columbia University is commemorating that moment with a provocative exhibition exploring the central role of African Americans in forging an identity for the US.

Titled 20 and Odd: The 400th Anniversary of 1619, the show quotes from a letter penned by the English planter and merchant John Rolfe, who noted the disembarking of “20. and odd Negroes” from an English pirate ship in August 1619. All of those Africans were sold into bondage onshore in exchange for provisions, noted Rolfe, who is perhaps better known today for his marriage to the Native American Pocahontas.

Ranging from archival documents to contemporary works of art, the exhibition at Columbia’s LeRoy Neiman Gallery “aims to subvert the primacy of the European perspective” in recounting this history, says Kalia Brooks Nelson, the show’s curator.

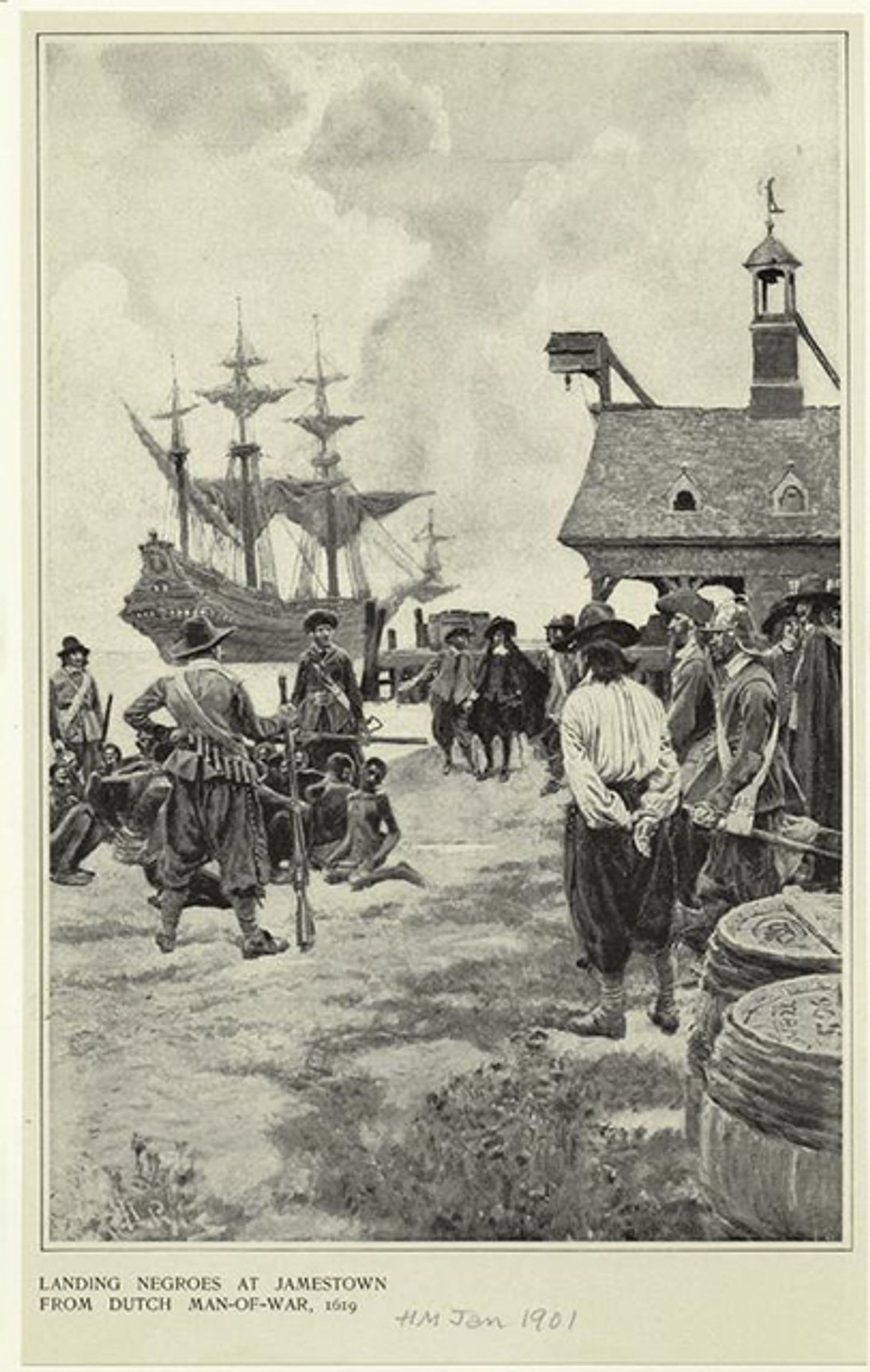

As an example, she points to an enlarged reproduction of an illustration published in 1901 in Harper’s Weekly depicting the Africans’ 1619 landing. “What you have in this image is a very idealised (even heroic) posturing of colonists as having confidently established their settlement on the shores of the Chesapeake,” while “receiving a crouching huddle of ‘Negroes’ along with other barrels of provisions disemboweled from the ship”, she says.

Howard Pyle, Landing Negroes at Jamestown From Dutch Man-of-War, 1619 (1901) Courtesy of New York Public Library

The show advances a critique of this perspective: In reality, those colonists would have been worn down from fighting the indigenous Powhatan tribes in the area, Nelson says. And the arrival of those doomed for enslavement and the hundreds of thousands to follow, she adds, was imperative to Britain’s success in colonising North America. Other objects strategically placed in the show also challenge the hierarchy of triumphant colonists and bedraggled Africans in that 1901 image.

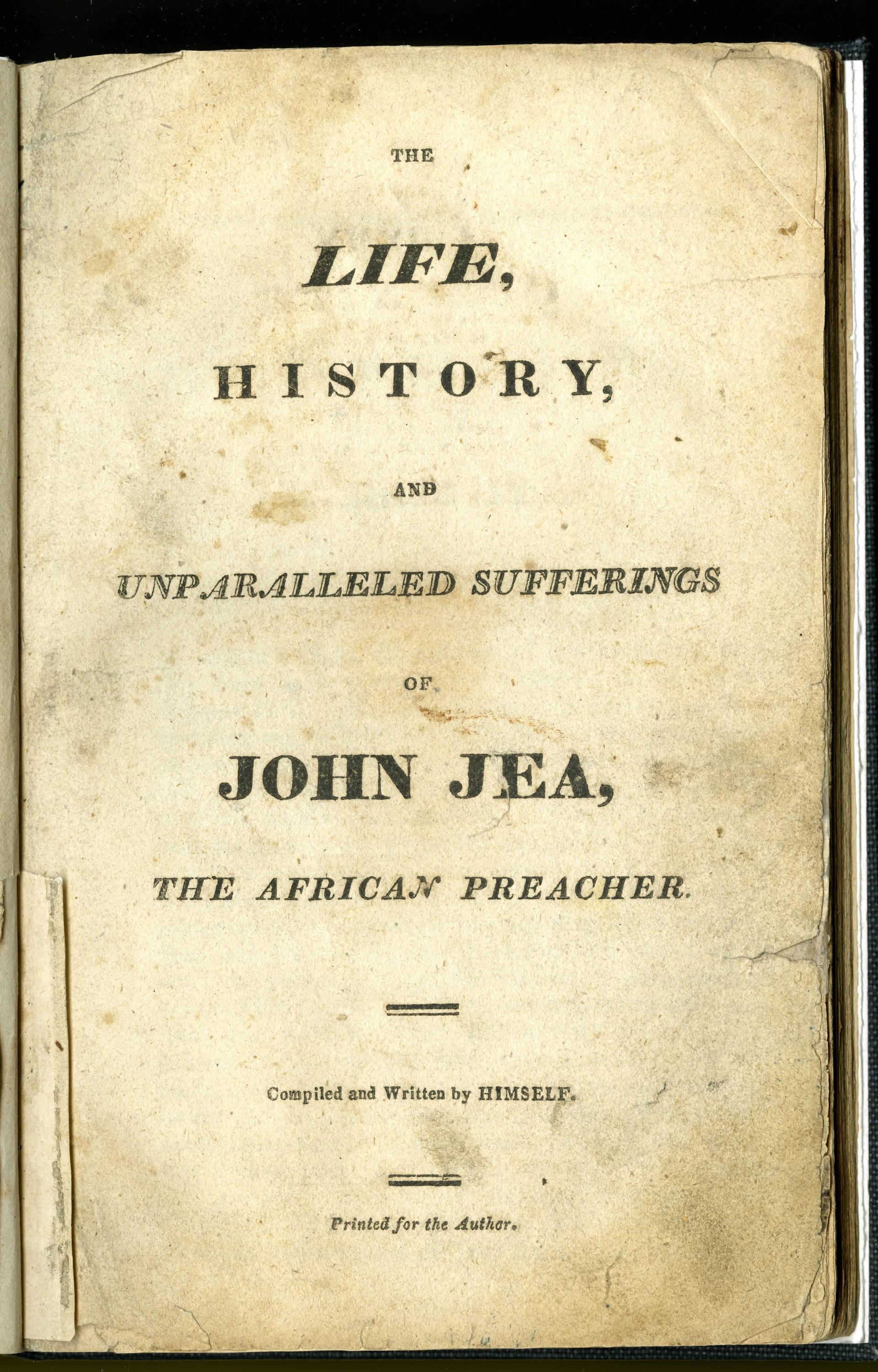

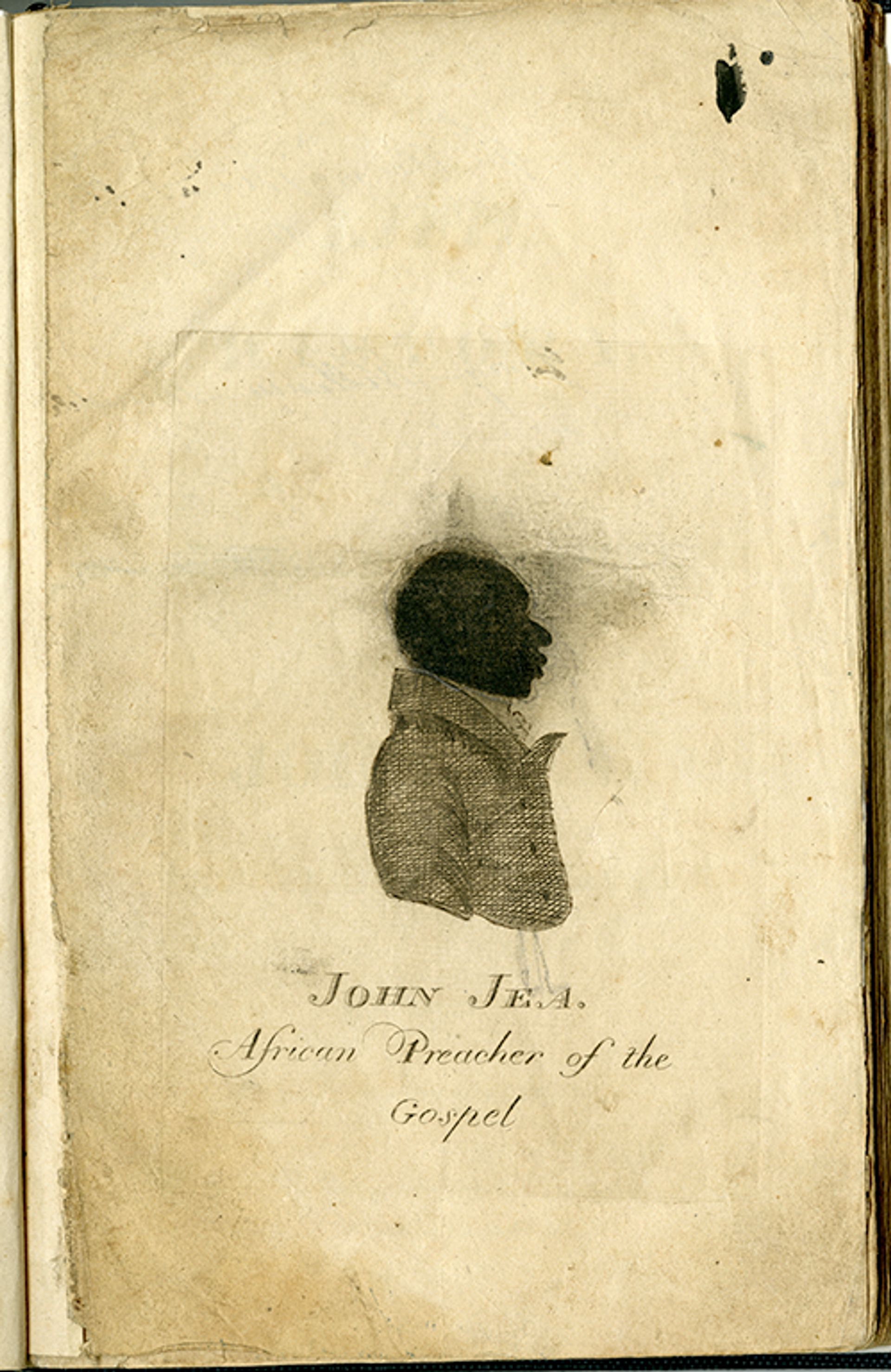

In line with that spirit of revision, the show documents a current of black literacy in America with the image of a frontispiece of a publication from around 1800 titled The Life, History and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher. “Some 200 years after the 1619 encounter we have evidence of African Americans maintaining knowledge of their African lineage,” Nelson notes, while authoring text that nods to both their “American- and African-ness”.

Frontispiece of The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of Jean Jea, the African Preacher, Compiled and Written by Himself (around 1800) Courtesy of Rare Book and & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

Frontispiece of The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, African Preacher, Compiled and Written by Himself (around 1800) Courtesy of Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

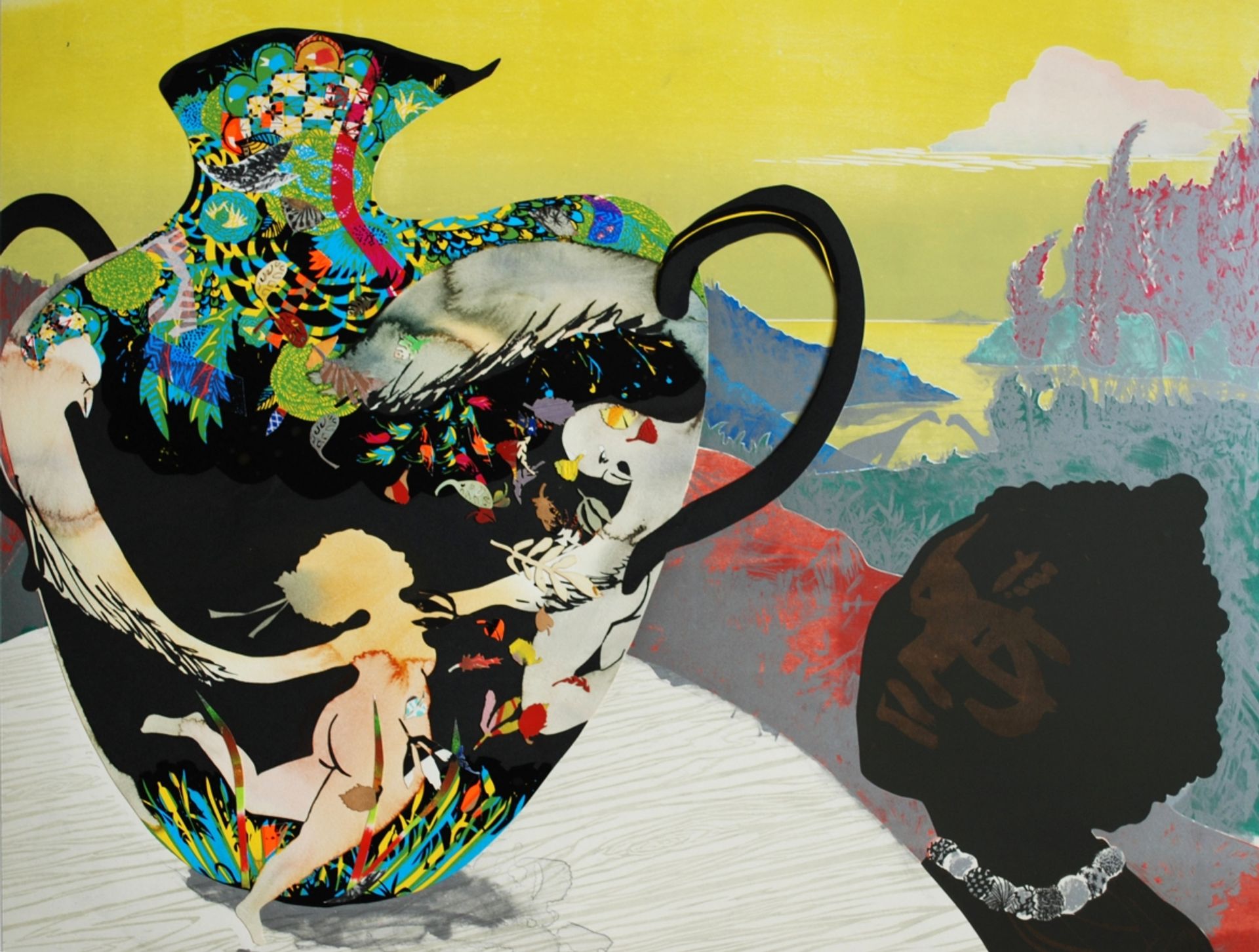

In an inventive approach, contemporary works of art drawn from the LeRoy Neiman Print Center at Columbia and from artists Nelson has worked with in the past enter into a dialogue with the vintage material, pointing up discord but also illuminating the multi-textured experience of the diaspora from the African continent.

Among the more recent works is Floating World: The Pasts They Brought With Them (2013), a paper collage with silkscreen and hand colouring by Sanford Biggers that evokes scattered remnants of history and African-American quilt-making traditions. Paula Wilson’s Remodeled (2007), a relief woodcut with offset lithography, silkscreen, collaged elements and hand colouring, testifies meanwhile to complex layers of histories and cultures.

Paula Wilson, Remodeled (2007) Courtesy of LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies, Columbia University

Ultimately, Nelson says, the goal is to demonstrate through myriad means how Africans and their descendants were crucial actors in what became known as the United States.

“America in its engineering is fundamentally a product of black genius,” she says. ”And the truthfulness of this perspective is available to us if we take the time to expose ourselves to the multiplicity of human experience.”

• 20 and Odd: The 400-Year Anniversary of 1619, LeRoy Neiman Gallery, Columbia University, New York, until 30 September