A marble cherub dating from 1705, an 1826 bust of Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm III and three oil landscapes by Sebastian Carl Reinhardt are among the treasures that quietly disappeared from Berlin’s Charlottenburg Palace in 2016, according to a list released by the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation last month.

These objects were on loan to the palace from the Hohenzollern family, the descendants of the last German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who abdicated on 9 November 1918 after Germany’s defeat in the First World War. His great-great-grandson, Georg Friedrich Prinz von Preussen, terminated the loans and demanded their return in an attempt to put pressure on the public authorities in a long-running property dispute.

Georg Friedrich, whose family ruled in Brandenburg and Prussia for more than 500 years, is demanding thousands of paintings, sculptures, porcelain, medals, furnishings, books and photographs from the states of Berlin and Brandenburg. Secret negotiations between the Hohenzollerns on one side, and the federal government and state governments of Berlin and Brandenburg on the other, were uncovered by the German media in July. The revelations have unleashed a storm of anger against the former royal family.

Georg Friedrich Prinz von Preussen, the great-grandson of the last German Kaiser, Wilhelm II © Patrick Van Katawijc / DPA / Alamy Live News

The objects in question are currently located in the former royal palaces and residences that now serve as museums in and around Berlin—in Oranienburg, Rheinsberg, Königs Wusterhausen, Sanssouci in Potsdam, Paretz, Schönhausen, Babelsberg, Cecilienhof, Charlottenburg and Pfaueninsel, according to Spiegel magazine. The publication reported that the museum at Grunewald and the Neue Pavillon in the park of Schloss Charlottenburg would be threatened with closure if all the claimed items were returned to the Hohenzollerns.

Beyond the former royal residences, the Hohenzollerns are also demanding 5,000 objects in Berlin museum collections, according to a July statement from the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The Alte Nationalgalerie, the Münzkabinett, the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, the Kunstgewerbemuseum the Ägyptisches Museum, the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, and the Deutsches Historisches Museum would all be affected. The claim encompasses works by Lucas Cranach, Adolph von Menzel, Friedrich Tischbein and Karl Friedrich Schinkel, as well as historic items such as the armchair in which Friedrich II died, Spiegel reported. A spokesman for the Brandenburg culture ministry confirmed that the claim encompasses “objects and paintings of considerable value and historical significance.”

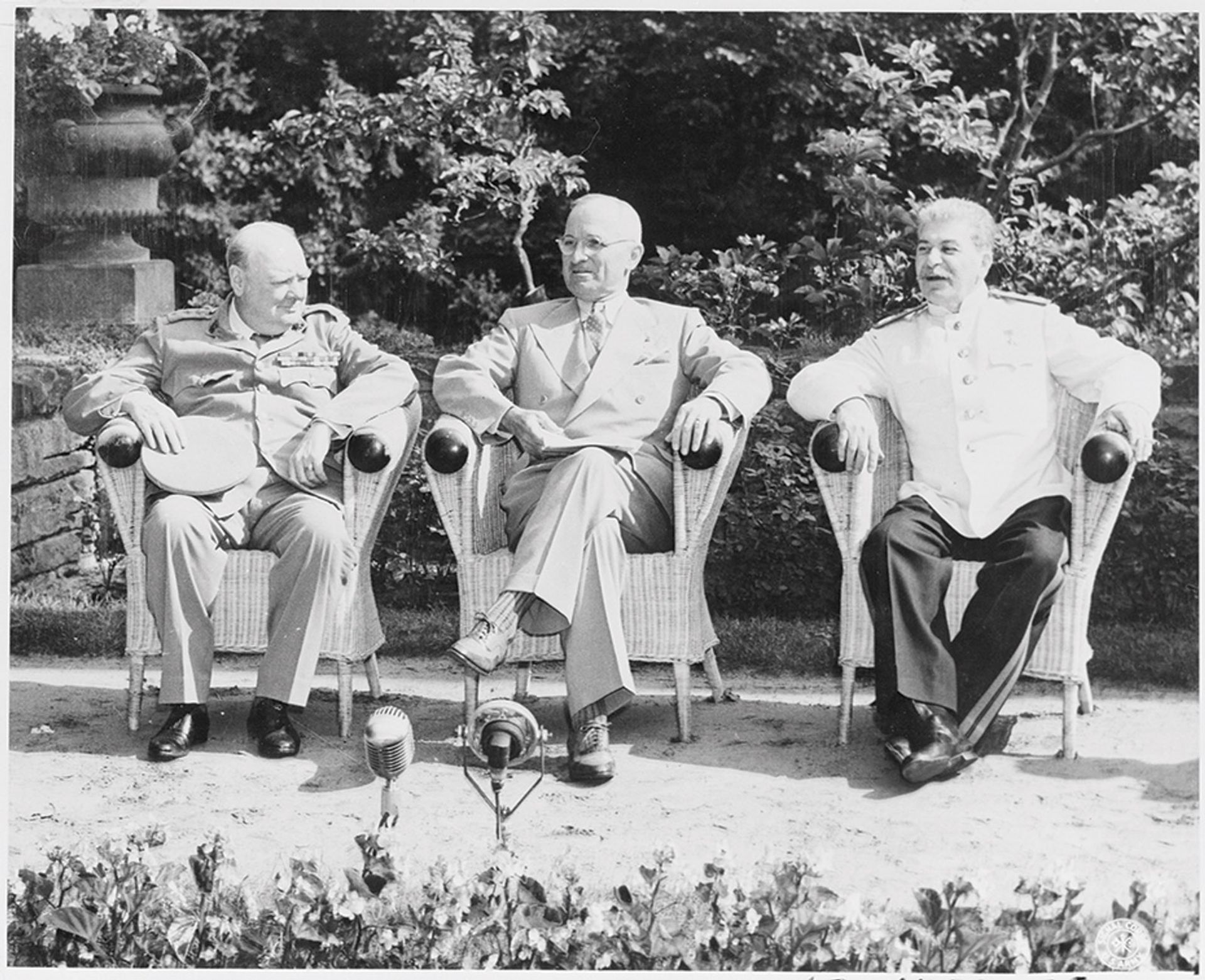

According to media reports, the prince is also demanding the right to live at Cecilienhof in Potsdam, the 176-room English-stately-home-style royal palace where Winston Churchill met in 1945 with the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and the US President Harry Truman to decide on the future of Germany. The federal culture ministry says it cannot comment on the talks because they are subject to a confidentiality agreement. “We will keep to this until we have a basis on which to negotiate a contract,” a spokesman says. A spokesman for the Berlin regional culture ministry also declined to comment on the talks because of non-disclosure agreements.

“The vast wealth amassed by the Hohenzollerns was generated by the people”

The negotiations, dating back to 1989, were first initiated by Georg Friedrich’s grandfather. The latest round of talks began in 2014. Martina Münch, the Brandenburg culture minister, told the regional parliament in August that the parties are “still very far apart.”

Before the First World War, Wilhelm II was by far the richest man in the country. When he abdicated in 1918, it was on condition that he could keep his possessions. Between 1919 and 1920, 63 railway wagons transported furniture, art, porcelain and silver to the imperial couple’s home in exile in the Netherlands. A second even bigger wave of deliveries followed in 1925. He was also awarded 66m marks and dozens of palaces, villas and other properties.

Schloss Cecilienhof was the location of the 1945 Potsdam Conference attended by Winston Churchill, Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin © National Archives and Record Administration

In August, the Left Party launched a petition under the headline “No gifts for the Hohenzollerns!” “These demands are completely unjustified!” the petition reads. “The vast wealth amassed by the Hohenzollerns over centuries was generated by the people. It was state property, financed from taxes, and should therefore be in public hands.”

But it appears that Georg Friedrich, a former technology management consultant who now focuses on the family businesses, is not primarily interested in the return of the objects; rather, he is trying to raise and improve the profile of his forefathers and is seeking to influence how the family is presented in public museums.

In an interview with Die Welt am Sonntag newspaper, he said any settlement would “on no account endanger objects on public display in museums.” The negotiations also encompass plans for a Hohenzollern museum in Berlin, according to the newspaper. Although Georg Friedrich denied that his family is demanding the right to define the museum’s narrative, he conceded that he is seeking a role in shaping it.

If the talks fail, the family’s claims could be assessed in court, Georg Friedrich said. “But neither we nor the public authorities want this, because it would take years and would be very expensive.”