An exhibition of Modern Arab art opening at the Sharjah Art Museum in November will focus on achieving gender parity among the artists on show. Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, an Emirati collector and professor, is organising the exhibition, along with the curators Suheyla Takesh and Salwa Mikdadi, using works from his Barjeel Art Foundation collection of Middle Eastern art. “This is an experiment, not an art historical hanging,” Al Qassemi tells The Art Newspaper. “I am not saying that these women influenced art history in the 1950s and 60s—a lot of them were unknown—but to say that they never did work is also unfair.”

Al Qassemi argues that female artists, and not just those from the Middle East, have been too-long forgotten in art history: “The issue has been gnawing at me since 2017, when I took a group of my students around the exhibition Modern Art from the Middle East," which was made up of works from Barjeel Art Foundation. “I apologised to them that only five or six of the 19 works were by women and they said to me that that was more than total number of works by female artists in the whole museum.” He then learned that, overall, works by women only total around 13% in US museums. Since then, Al Qassemi has been rapidly collecting art by female artists.

When Al Qassemi realised that half of the current display of Barjeel Art Foundation works would have to be changed (its show A Century in Flux: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation opened in May last year and will continue until 30 May 2023) due to an upcoming travelling exhibition in the US, he took the opportunity to plan a show that tackled the issue of gender. Rather than exclusively show works by women, he decided to present them alongside their male contemporaries in as close to a 50-50 split as possible. “The people need to be willing to see everything on a par,” he says.

Mariam Abdel-Aleem's Clinic (1958) Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation

Collecting art by female Modern artists in the Middle East has been a challenge, according to Al Qassemi. A dearth of scholarship in the field has led to less conventional research methods. “I’ve found most of the latest acquisitions through social media,” says Al Qassemi. He found the work of the Iraqi artist Naziha Salim, the sister of the well-known painter Jewad Selim, on Instagram and purchased a painting for his collection. Having heard of the Egyptian artist Menhat Helmy, he posted on Twitter asking for more information and ended up in touch with her grandson, who is now documenting her previously untouched body of work in Cairo. "Her work is mind-blowing: she did portraits, she made abstract work, she did political work—previously there were only three lines about her on the Internet," Al Qassemi says. Her paintings Space Exploration/Universe (1973) and Outpatient Clinic (1958) are now in the Barjeel collection.

The upside to collecting in a field that is relatively undocumented is that the prices are much lower. The market for Modern Arab art has grown rapidly in recent years as museums in the region have sprung up; shows about Middle Eastern art have proliferated, and the availability of high-quality pieces has declined. “For the price of one work by Dia Azzawi, for example, I can buy five or six works by female Arab artists,” Al Qassemi says. “It’s frustrating because I am against this sense of value but it is also enabling me, too.”

Once the works by women enter the Barjeel Art Foundation collection, biographies for the artists are added to the foundation’s website. In the last few months the collection has added works by Bibi Zogbé, Mariam Abdel-Aleem, Asma Fayoumi, Juliana Seraphim and Safia Farhat, among others.

To prevent the works being solely distinguished by the gender of their makers, Al Qassemi has decided to display the labels at a distance from the art. “We did the same thing with our show at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 2016, when we showed 40 works from their collection and 40 from ours,“ he says. “The visitors asked: Is this by an Iranian? Is this an Arab? In the end, the idea is that the essence is the same—both talk about things we have in common, from injustice and colonialism to religion and calligraphy. That's why that exhibition was so important.”

The idea of enforcing a gender quota on an exhibition came under fire when Al Qassemi first announced it on his social media accounts in July. "Art should be chosen based on the feeling it gives you / messages included / how it fits into the theme of the exhibition,” said one Facebook user while another added that the plan would “sacrifice a hierarchy of competence for the sake of ‘equality’”.

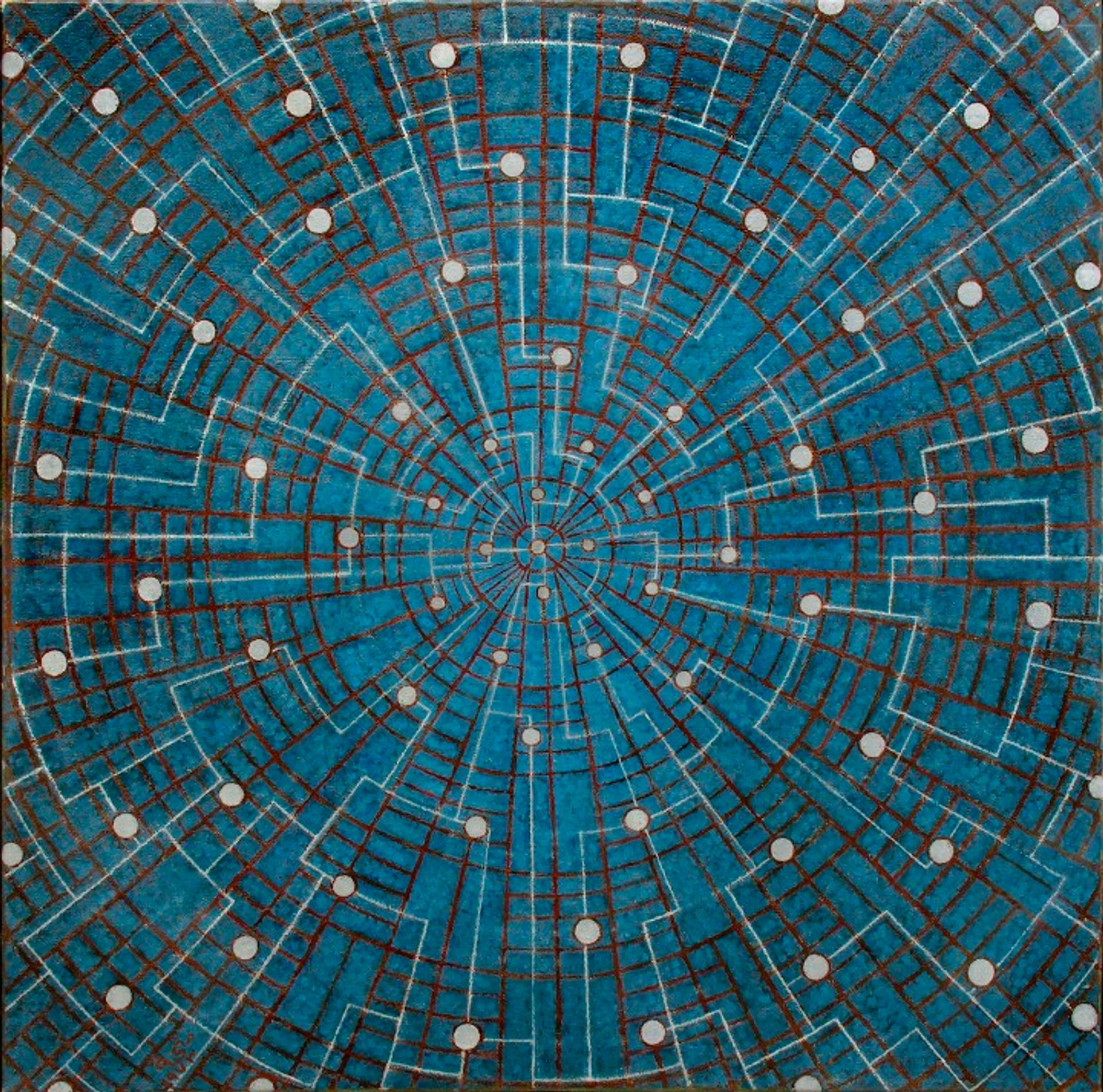

Menhat Helmy's Space Exploration/Universe (1973) Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation

But others have supported Al Qassemi’s vision: “I am happy to agree that gender ‘should be’ irrelevant. But precisely it is not; not yet, in 2019, indeed,” said Omar Berrada, a New York-based writer and curator who is the director of the Marrakech artists' residency programme Dar al-Ma’mun. “To the extent that the rules of this game have been and still are set by men, abstract notions of 'meritology' or 'quality' are meaningless. I'd say the point here is not to show ‘the best’ according to whatever the established canons of taste dictate, but perhaps to allow your intervention to propose possible shifts in our skewed perception of the history of Modern Arab art.”

Al Qassemi says he believes in affirmative action: “The world has been so grossly unfair to women, and I believe in the quota system to make sure women are in classrooms, on boards of organisations—and in museums.”

• The Barjeel Art Foundation's travelling exhibition Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s will take place over two years starting in January: Grey Art Gallery at New York University (14 January 2020-4 April 2020); Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University (28 April 2020–26 July 2020); Johnson Museum at Cornell University (22 August 2020–13 December 2020); McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College (25 January 2021–6 June 2021); and University of Michigan Museum of Art (25 June 2021–19 September 2021).