The sleeper exhibition of 2018 in London was a show at the British Museum called Charmed Lives in Greece, about the art and friendship of three men: the writer Paddy Leigh Fermor, the painter John Craxton and the Greek artist and intellectual Niko Ghika. It became a bit of a cult among lovers of Greece and in literary and gay circles (Craxton’s paintings of Greek matelots are especially appreciated), and the catalogue by Evita Arapoglou sold out long before the end of the show.

Of the three, the least well known in the UK and the US is Ghika (full name: Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, 1906-94), for a reason that applies to many intellectuals of his generation from southern and eastern Europe. In the 1930s they gravitated toward Paris as the centre of the civilised world, but when the world’s art capital shifted to New York after the war, this tended to leave them out of the canon of 20th-century art history.

But Ghika had known many who were to become household names. He was a close friend of Christian Zervos, the critic and founder of the influential review Cahiers d’Art, and hung out with Arp, Léger, Braque and Le Corbusier. Like many other Greeks of his generation, he was looking for an escape from the academic neo-classicism that Greece’s Bavarian rulers had so easily imposed on the birthplace of classicism. He absorbed the influences of the Parisian avant-garde before settling down to his own geometric, almost architectural way of painting, mainly of expressionist landscapes.

Ghika is very much alive in the memory of the Greeks today and is considered one of their best painters. Jacob Rothschild, who is an admirer of his work and has six of his paintings at his house on Corfu, has now paid a huge tribute to him and to Greece (the bicentenary of its independence falls in 2021), by commissioning a seven-fold enlargement—from 34cm to 2.5m—of two of Ghika’s statues, to stand on a promontory overlooking the strait between Corfu and Albania.

With this project, Rothschild is also remembering the 50th anniversary of finding the house with his mother, Barbara (née Hutchinson), who made what was to be a happy marriage with Ghika in 1961 after miserable marriages to Victor Rothschild and the writer Rex Warner.

Rothschild says of his stepfather, “Ghika was unbelievably inward-looking, very thoughtful, very old-fashioned; he didn’t speak much—his great interest was painting. I knew him well, yet he was a person you couldn’t know really well because he did not wear his heart on his sleeve. When we set up house here, which was after his own great house on Hydra burnt down, at first, as a proud Greek, he rather resented the fact that we had settled on his turf, but then he grew to love it and painted it many times.”

The American writer Henry Miller’s poetic take on Ghika in his Colossus of Maroussi is, “I saw a new Greece, the quintessential Greece which the artist had abstracted from the muck and confusion of time, of place, of history. I got a bifocal slant on this world which was now making me giddy with names, dates and legends. Ghika has placed himself in the centre of all time, in that self-perpetuating Greece which has no borders, no limits, no age.”

In fact, the subject matter of these sculptures is from the legend relating to the island, for every place in Greece is imbued with the memory of gods and goddesses, myths and history. Corfu’s memory is of Odysseus and Nausicaa. It is thought to be the island known in antiquity as Skeria, on which the hero of the Trojan wars, Odysseus, is washed up toward the end of his perilous return to Ithaca. Ghika represents him as a bearded weather-beaten figure, hiding his nakedness behind a bush from young Nausicaa, the daughter of the king, who is about to throw a ball.

Ghika has taken the ancient story and reimagined it in free, expressive, semi-stylised forms with a rough, tactile surface as unlike smooth neo-classicism as it is possible to be. When he carved the maquettes (models) in clay in 1948, he had already illustrated a poem by Nikos Kazantzakis (author of Zorba the Greek) based on The Odyssey, with a scene very like this charming episode among a series of grisly adventures. The maquettes were exhibited in London at the Leicester Gallery in 1953, and he left them to the Benaki Museum in Athens, where they can be seen in his apartment there.

In 1972, George Rallis, then Greece’s prime minister, wrote a moving letter to Ghika expressing the hope that he would make large-scale versions of them for Corfu. Rothschild added sympathetic comments, but what finally gave him the impetus to carry this out was his friendship with Adam Lowe of the Factum Foundation, which specialises in high-tech reproductive methods.

How the models were enlarged

In the past—for example, when Henry Moore’s sculptures were enlarged from tiny models to the huge pieces that stand outside public buildings—a pantograph was used: that is, a mechanical system of rigid bars that takes measurements at numerous points of the original and scales them up, but this cannot give the texture of the original.

Factum used a highly detailed digital photographic method instead. “We did not have Ghika present to advise us,” says Lowe, so they worked from small bronzes that had been cast from the maquettes in Ghika’s time, to which the artist himself had given the finish, which they wanted to recreate as exactly as possible.

The first phase was to record them using photogrammetry, a 3D recording technique that employs 2D images to create a 3D model of an object or surface by taking hundreds of overlapping photographs of an object from many different angles and processing them by using software such as RealityCapture (RC). The data was then processed and scaled up to a height of 2.5m. The information was routed into medium-density polyurethane, and once the different parts of the sculpture were milled, they were glued together. To match the aesthetic of the original sculpture, the surface of the milled enlarged positives was retextured manually.

At this point the high-tech part of the operation was over and the traditional skills of the Kaparos foundry near Athens were marshalled, supervised by Alekos Pappas, son of the Greek sculptor Iannis Pappas, who had regularly used this highly skilled workshop and had been a friend of Ghika.

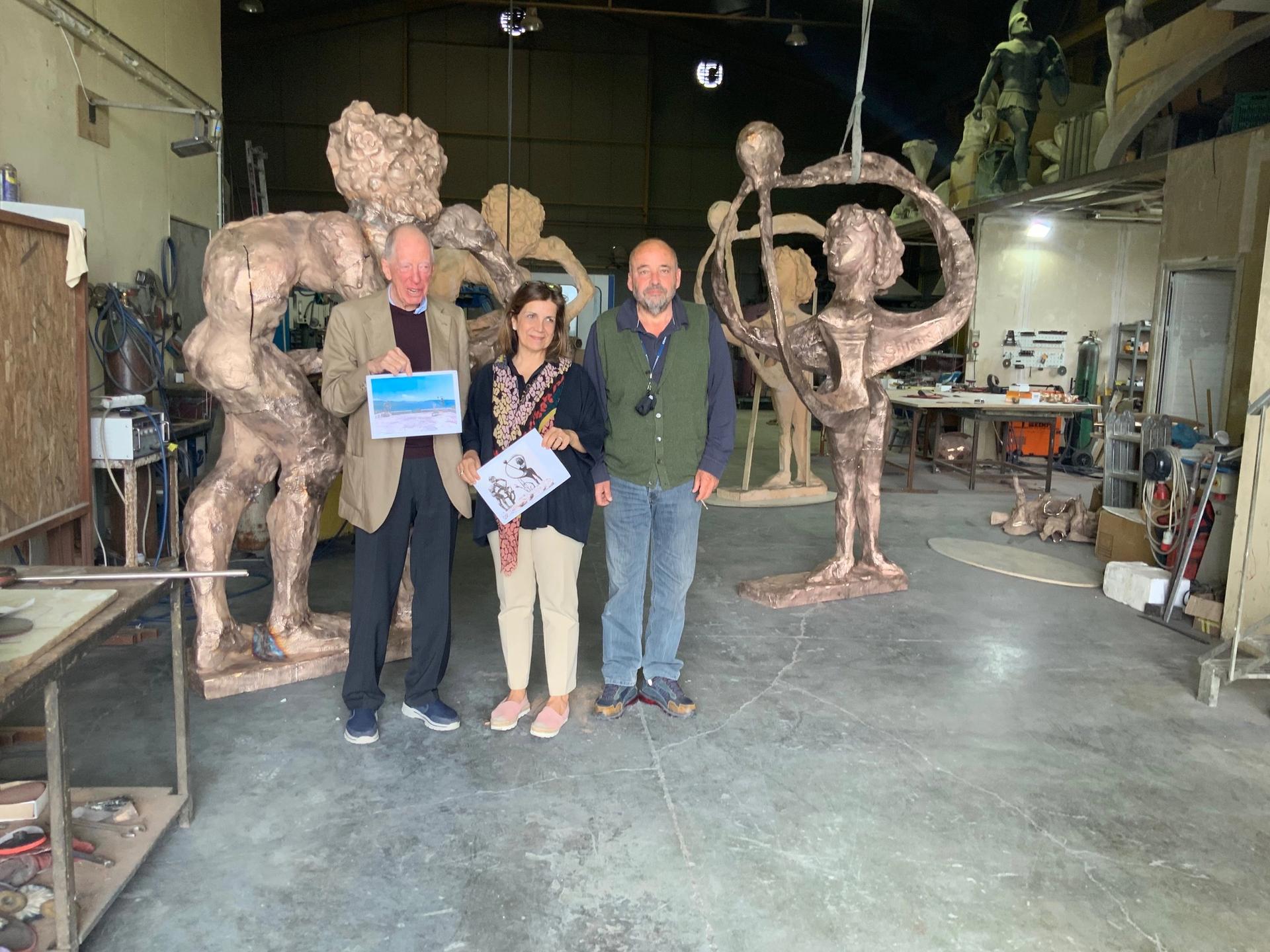

From left, Jacob Rothschild; Evita Arapoglou, the biographer of Niko Ghika; and Alekos Pappas at the Kaparos foundry with the figures of Odysseus and Nausicaa before patination

The technique was essentially the same lost-wax method used by the great sculptors of the Renaissance such as Benvenuto Cellini, but with some modern improvements. The figures were cast in parts, 20 for Odysseus because he is a complex figure, and 11 for Nausicaa. The ceramic shell casting technique was used to make both the moulds of the positives that had arrived from Madri and the inner cores so that the sculpture would be hollow, because bronze distorts if it is cast too thick. Molten wax was poured into the gap and the whole was put into a furnace, where the wax was burnt off and replaced with molten bronze.

After that, the separate parts were worked on with chisels to remove any irregularities left over from the casting process, gas-welded together with a steel frame inside to strengthen the whole sculpture and patinated to yield the deep brown colour. In another modern innovation, the bronze contains a small percentage of silicon, which makes it flow more easily.

Odysseus and Nausicaa now stand on stone bases with turntables so sensitive that can be moved with the touch of a finger to face either the sea or the house. At night they will be lit so that ships passing through the strait will have a view of the presiding Homeric hero and heroine of the island. The promise made 50 years ago has finally been fulfilled.