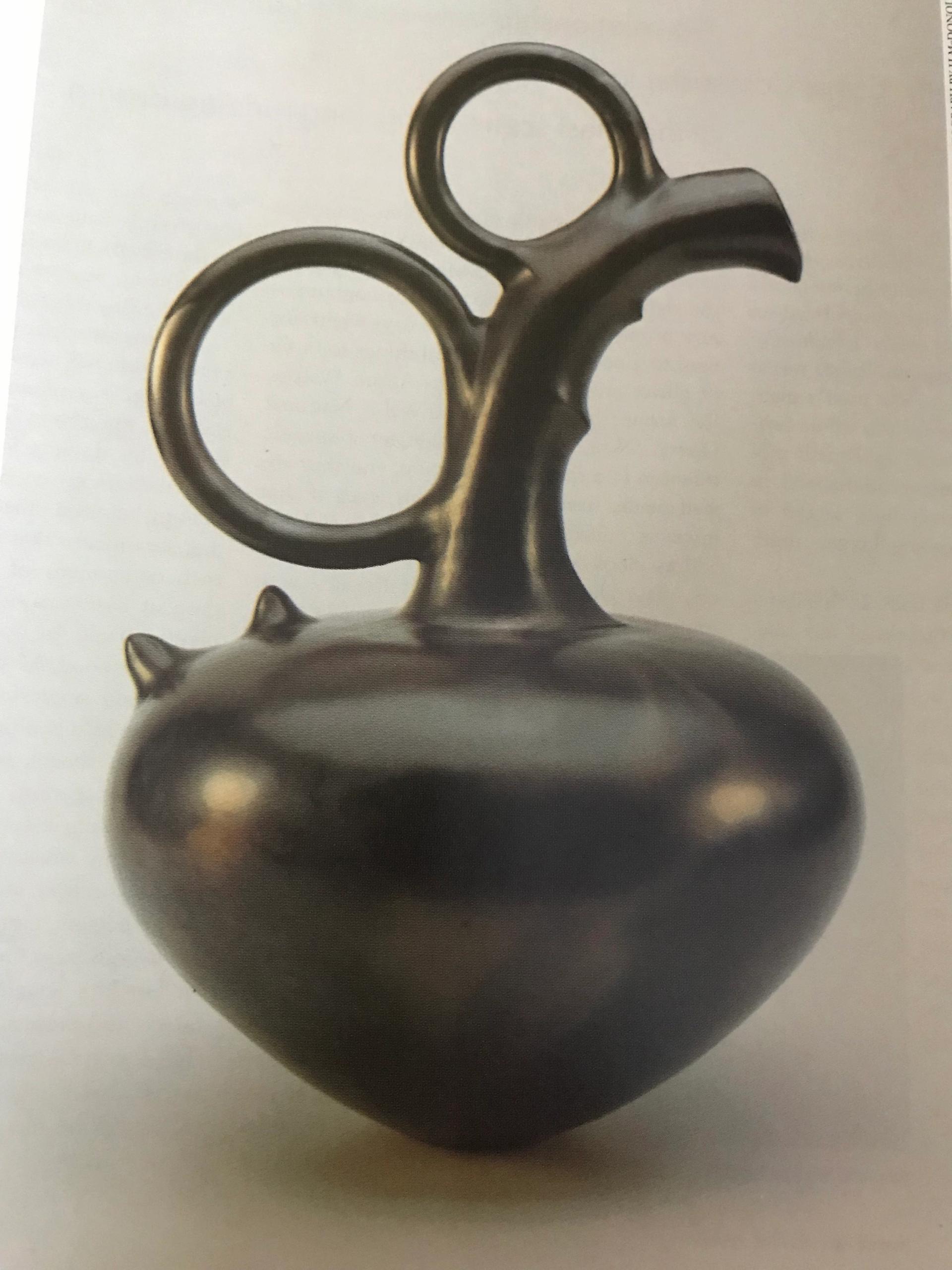

I first wrote about Magdalene Odundo back in 1992 in a piece for Crafts Magazine that was devoted to a single softly gleaming black pot. Now the same Asymmetrical Reduced Black Piece (1992) in burnished and carbonised terracotta, with its arching spout, looped handles, sprouting nodules and gleaming bulbous body is one of the stars of a major survey show celebrating Odundo. The Journey of Things (until 15 December 2019) transports Odundo's work (accompanied by some inspirational objects) from the Hepworth Wakefield to the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich. “Her work cannot be pinned to time, place or culture," my earlier self declared, before listing her influences as “plant pods, thrusting stamens, the swell of a seed pods, classical vessel shapes from African and European antiquity… and even the ballooning sleeves and severe bodices of Elizabethan costume”.

Twenty seven years later, examples of all the above and a great deal more have been brought together in this show. They are placed alongside four decades of her own output as physical evidence of what feeds into her suggestive and utterly distinctive vessels. There’s a series of stunning botanical photogravures by the German photographer Karl Blossfeldt along with textiles and ceramics from all periods ranging across Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe. Odundo’s pots also sit comfortably alongside specially selected pieces by many of the artists that she reveres, including Degas, Rodin, Moore, Hepworth and Gaudier- Brzeska as well as more recent presences such as Yinka Shonibare and El Anatsui.

Magdalene Odundo's Asymmetrical Reduced Black Piece 1992 Courtesy Louisa Buck

Although at Hepworth Wakefield the show was designed by Farshid Moussavi, David Adjaye has taken the reins as architect for its Sainsbury Centre incarnation. Here the groups of exhibits are displayed on variously sized circular grey ‘islands’ which also resemble giant millstones as well as Brancusian sculpture bases. For Norwich, Odundo has also included a rare sortie into another medium—a major installation of 1001 suspended hand-blown glass elements in a configuration partially influenced by the murmuration of starlings that flock over the city at dusk. They could just as easily be read as an engulfing swarm of jellyfish though, or an ominously hovering invasion of alien life forms.

Back in 1992 I rather simplistically declared that “in works such as these, demarcations between art and craft are not only irrelevant, they are absurd”. But as this exhibition amply confirms, the strength of all Odundo’s work is the way in which it uniquely draws on, resonates with and distills such a wide range of languages, forms and visual cultures that it defies any single reading or categorisation. As Odundo herself put it at last week’s opening, what she makes is “based on what is human in all of us”.