In yet another example of juxtaposing contemporary art with an august museum collection, the Oriental Institute (OI) of the University of Chicago is marking its centennial by inviting three artists to present works inspired by Middle Eastern artefacts.

The Ohio-based artist Ann Hamilton will create an installation at the university’s Regenstein Library in which she affixes a series of translucent images of objects from the institute to a reading room’s vast glass dome. Jointly titled aeon, the images were produced by the artist by using desktop and hand-held wand scanners. “After several thousand years entombed underground and nearly a century enclosed in the OI’s display cases, the ancient figures are ‘animated’ through Hamilton’s ethereal images,” the institute says.

Jean Evans, the chief curator and deputy director of the Oriental Institute’s museum, says that by placing the images on the glass dome, Hamilton will explore the possibility of “taking the archaeological artefacts outside of the place you expect to see them”.

“There’s a wonderful contrast between digging things up the ground and literally putting them in the sky,” Evans says.

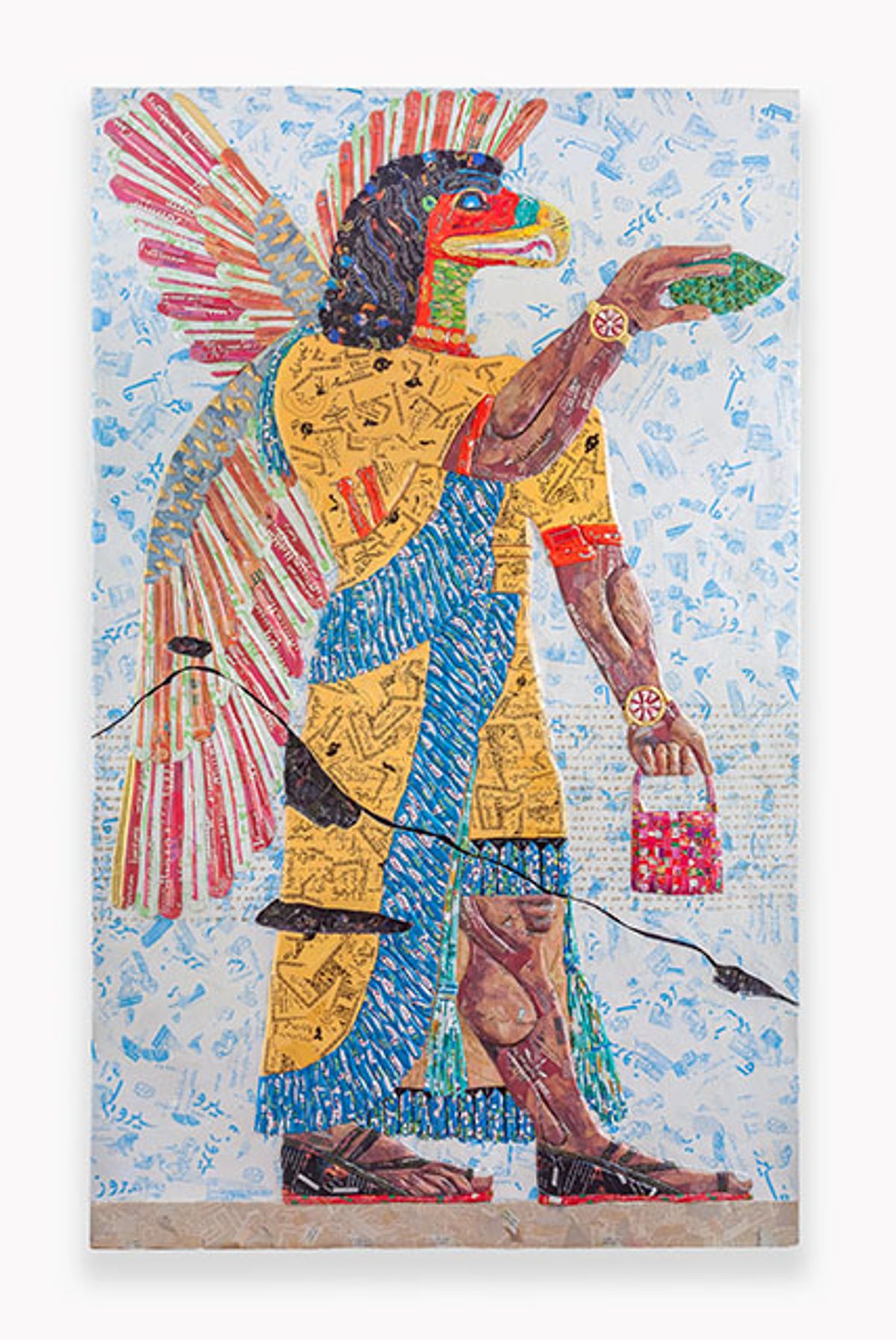

The Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz will create a site-specific installation that completes a fragment of a relief at the institute depicting the head of an Assyrian king. The work extends a series by the artist titled The invisible enemy should not exist, in which he uses contemporary Middle Eastern newspaper clippings and Iraqi food packaging to recreate reliefs from the Northwest Palace in the ancient city of Nimrud in northern Iraq. The palace was destroyed by members of the Islamic State in 2015.

This is not the first collaboration between the Oriental Institute and Rakowitz. In a 2017 commission from the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the artist filmed a stop-motion work in the institute’s Mesopotamian gallery, The Ballad of Special Ops Cody, in which an American action figure interacted with ancient statues.

The Syrian artist Mohamad Hafez will serve as an “interpreter in residence” at the institute, exhibiting his own works while linking the ongoing destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East to the deaths and suffering there. “It’s about longing, nostalgia, the displacement of people across time and place,” Evans says. “It’s a step away from our artefacts to remind people what’s going on in the region today.” Hafez will also create programming elsewhere across the University of Chicago campus.

The works will be unveiled at a celebration on 28 September and remain on view through the 2019-20 academic year.

Founded at the University of Chicago in 1919, the Oriental Institute leads archaeological excavations and research projects in the Middle East and has amassed a collection of some 350,000 objects. Amid the strife in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere in the region, its mission also includes maintaining databases of missing works and using satellite imagery to track looting, Evans notes. “Everyone who works here can’t help but be affected by what’s going on there,” she says.

Displaying contemporary art offers the institute yet another way of engaging with issues in the Middle East today while also connecting with visitors, Evans suggests. “We reinforce the connection between these collections that are largely the product of early-20th-century archaeology and a living, breathing institute with scholars and researchers.”