On an autumn morning in AD79, as the earth groaned and shivered and an ominous cloud towered ever higher over Mount Vesuvius, somebody was making chicken stock in a modest taverna set in a small vineyard, a block from the arena in Pompeii. Nobody would ever eat the soup: the pot boiled dry as the most famous volcanic eruption in history destroyed the Roman town.

Many exhibitions on Pompeii have concentrated on the terror of its last hours. A show at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford celebrates life through food: the wine, olive oil, fruit and vegetables from the fertile slopes around the town; the reeking fish sauce added to all savoury dishes; the goats, rabbits and chickens immortalised in wall paintings; the food shared with guests in magnificent banquets or bought from fast-food shops in the street; and the food offered to the gods or sent into eternity with the dead.

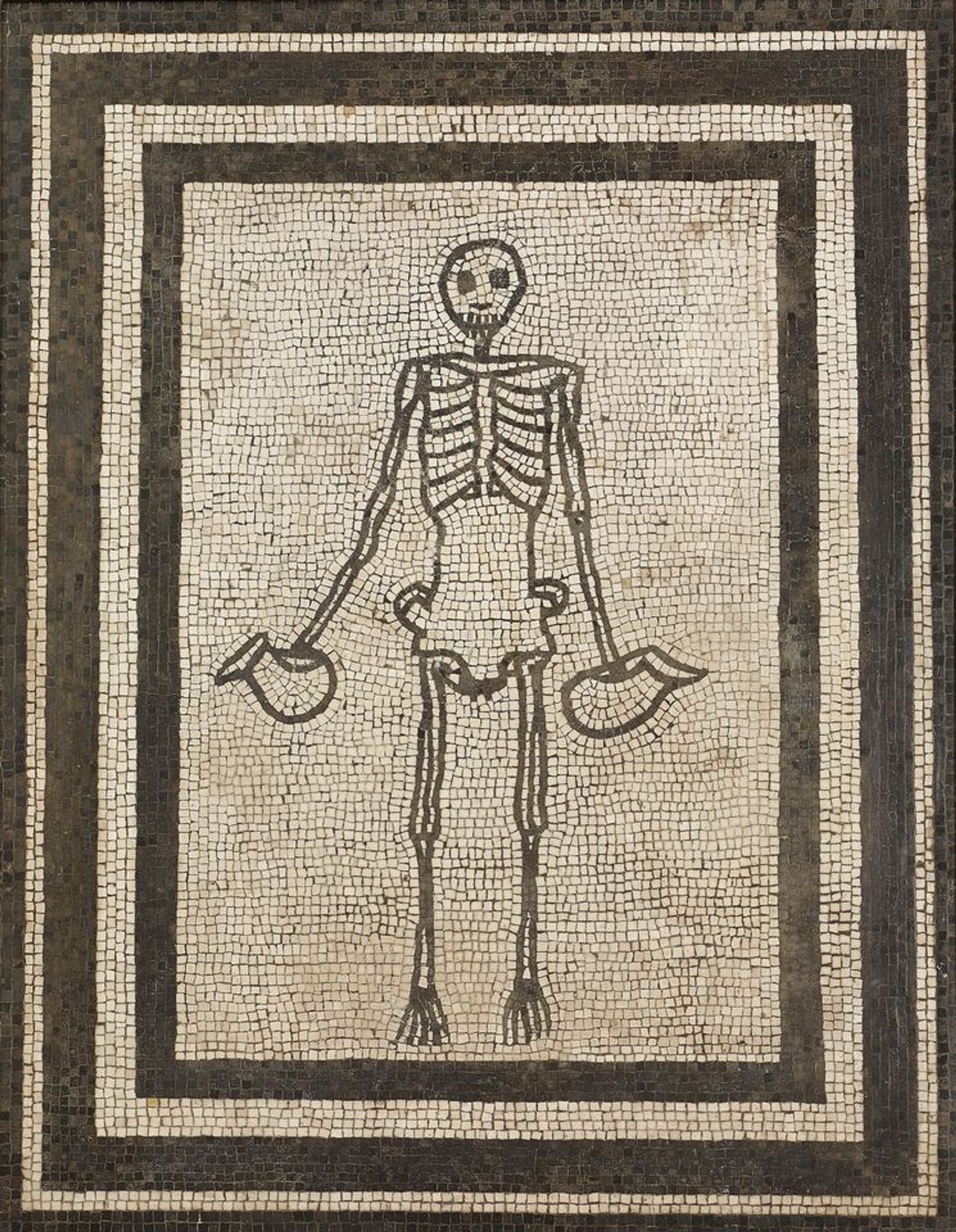

A monochrome mosaic panel (AD 1–50) from Pompeii’s House of the Vestals © Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

“We’re all going to die, but we’re going to have a damn good meal first”

The exhibition includes around 300 objects, with remarkable loans coming from the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli and sites around the volcano, many leaving Italy for the first time. Among these are fine sculptures, frescoes and mosaics, but also touchingly prosaic objects such as a carbonised loaf placed in the bakery oven on that last morning, and a glass jar of solidified olive oil, which when its stopper is removed still has a faint grassy scent.

Chicken bones in a pot were exposed for the first time in 2,000 years in the rooftop laboratory of the Ashmolean, as the conservator Alexandra Baldwin chipped away tiny flakes of corrosion with a scalpel. The small bronze pot came in a load of shabby cookware from the Naples museum, all originally from a modest taverna grandly known as The House of the Lararium of Hercules, which had a takeaway counter by the street and a small more formal dining area in the garden.

It is the first time Naples has allowed an outside museum to carry out conservation work on its artefacts. Baldwin’s delicate cleaning has revealed that the pots and pans must have been secondhand, originally made for a much grander establishment. Several were repaired with lead or neat riveted metal patches, and a kettle gained a new lid crudely cut down from a larger vessel with a nail hammered through for a handle.

Conservator Alexandra Baldwin with the potential urinal in the Ashmolean’s lab © Ashmolean Museum

Hours of eating and drinking had inevitable consequences: unusual corrosion of one pot, and a lip apparently designed to prevent splashback, have raised suspicions in the minds of Baldwin and the show’s curator Paul Roberts that two vessels with handsome handles were not wine bowls as previously thought but portable urinals brought to the reclining diners by slaves.

“This is the show I have always wanted to do,” Roberts says. To him, the battered pots and the evidence of unending work that went into feeding the Roman town are personal. He was brought up in his mother’s restaurant in Ross-on-Wye, where her saucepans were pre-war like much of the kitchen equipment. Moved by the copious evidence of last meals being prepared for rich and poor across the site, he has no time for the theory that Pompeii was half deserted by AD79, a ghost town after an earlier earthquake: upstairs from a brothel, one of the most famous buildings, a stew of onions and beans was being prepared for the workers.

Roberts relishes a mosaic from a dining room floor, coming from Naples. It shows a grinning skeleton carrying two wine jugs. “That’s it,” Roberts says, “that’s the whole thing—we’re all going to die, but we’re going to have a damn good meal first.”

The main sponsor of the exhibition is the Italian bank Intesa Sanpaolo.

• Last Supper in Pompeii, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 25 July-12 January 2020