As the world’s leading expert on Egon Schiele and the author of his catalogue raisonné, Jane Kallir is accustomed to being contacted out of the blue by strangers claiming to have found a possible drawing by the Expressionist artist.

“Ninety percent of the time they’re wrong,” says Kallir, the director of Galerie St Etienne in New York, who has been authenticating Schiele drawings and watercolours for over 30 years. “Most of them are fakes—egregious copies.”

So Kallir was floored when a genuine Schiele emerged from a seemingly unlikely source: a Habitat for Humanity thrift store in Queens, New York. Now on view at her gallery with an estimated value of $100,000 to $200,000, it was sketched by Schiele in 1918, not long before he died in Vienna at age 28 in the Spanish flu pandemic.

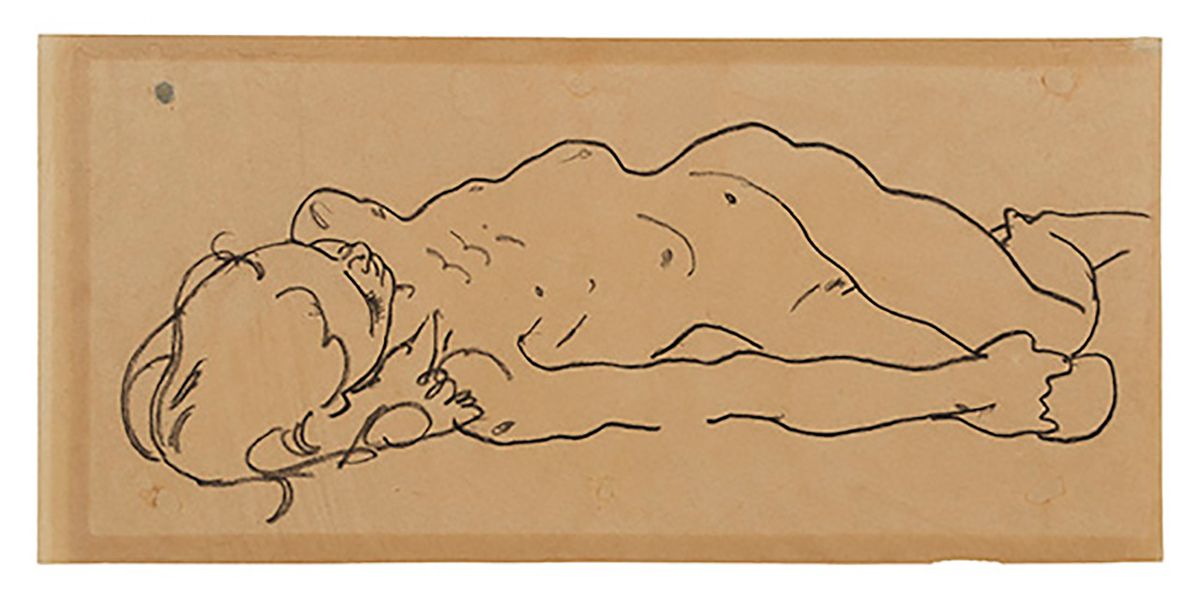

Given the abundance of fakes she encounters, Kallir had initially been skeptical when a man contacted her by email in June 2018, attaching blurry photographs and informing her that he had found and purchased a possible Schiele. She asked him to send a better photograph of the drawing, which depicts a nude young girl lying face up and was executed in pencil on paper.

Almost a year passed before he again contacted the gallery in May this year and sent a sharper photo. When she saw it, Kallir was intrigued. “I thought there was a good chance” it was genuine, she says. She invited the owner to show her the drawing at the gallery.

To her satisfaction, it was authentic. “It was a girl who modelled for Schiele frequently, both alone and sometimes with her mother, in 1918,” Kallir said. Researching further, she could place the work within a sequence of 22 other Schiele drawings that exist of the girl, even pinpointing two that were probably executed in the same modelling session. Many of those drawings were studies for Schiele’s final lithograph, Girl.

“If you look at the way this girl is lying on her back, and you look at the foreshortening both on the rib cage and on her face, and the way you see that little nose pointing up—think about how difficult that is to do,” she says. “There are very few people in the history of art who can draw like that.” More objective elements like the type of cream wove paper and the black pencil used also supported the authentication, she adds.

Other drawings of the girl are currently in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Leopold Museum in Vienna.

When he brought the drawing to Galerie St Etienne, the owner related that he had found it while browsing in Queens at a Habitat for Humanity ReStore, which sells donated overstock and second-hand items like furniture, appliances, home decor and building materials.

Kallir described the man as a part-time art handler who often visits second-hand shops. “He’s got some art background—an eye,” she says. He prefers to remain anonymous, Galerie St Etienne says, and so was unavailable for an interview.

“I don’t know offhand what he paid for the drawing,” Kallir says of the sharp-eyed picker, “but it was not very much.” She estimates that the drawing, which is now for sale through the gallery, is worth roughly $100,000 to $200,000. It is currently on view there in an exhibition titled The Art Dealer as Scholar, which features works by Schiele, Käthe Kollwitz and Alfred Kubin and runs through 11 October. The show also includes an impression of Schiele’s 1918 lithograph Girl and a drawing by the artist of the girl’s mother.

If and when the drawing is sold, the gallery says that its owner plans to donate some of the proceeds to Habitat for Humanity, a non-profit organisation that builds and repairs homes for people in need.

Contacted about the drawing by The Art Newspaper, Karen Haycox, the chief executive of Habitat for Humanity New York City, expressed surprise at the discovery. “We are ecstatic!” she said in an email. “And, maybe a little bit in shock but ultimately really happy for all involved.”

“I can’t help but think that were it not for the Habitat NYC ReStore, this piece of art history might have ended up in a landfill, lost forever.”