The walls of the office of Anthony Amore, the chief of security of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston since 2005, are covered with reproductions of all 13 works stolen in one of the biggest unsolved art thefts in history, when two men posing as police officers made off with treasures by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Degas, and Manet on 19 March 1990. At Amore’s home, drawings by his daughters of Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, one of the works that was taken, hang on the door of his refrigerator. “I’m still wildly obsessed, more than ever,” he says. “I constantly think about those paintings.”

Geoffrey Kelly, the FBI’s lead investigator on the theft since 2002, who works closely with Amore, considers himself “equally obsessed”. On a wall in his finished basement at home is a reproduction of The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, that his wife gave him three years ago. “She frayed the edges because the painting had been sliced out of the frame,” Kelly says.

Despite more than 30,000 leads, hunches, forensic tests, psychic visions, jail house confessions and hundreds of interviews with drug dealers, mobsters, retired police officers, journalists, museum directors, museum guards and art dealers in the US, Europe, Asia and South America, authorities are still no closer to knowing the whereabouts of the works. And although the art has been estimated for some time to be worth $500m, the skyrocketing art market has led some experts to raise the figure significantly. “It’s at least $1bn,” says Otto Naumann, a senior vice president of Sotheby’s and a dealer in Old Masters for more than 30 years. “The Vermeer [The Concert] alone is worth nearly $500m.”

Johannes Vermeer, The Concert (1663-66) was Isabella Stewart Gardner's first major art purchase. Experts estimate the missing masterpiece is worth nearly $500m today Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

The Vermeer alone is worth nearly $500m.

The theft was explored last year in a ten-part podcast called Last Seen, a joint project of radio station WBUR, a National Public Radio affiliate, and the Boston Globe, which tracked down one lead to Florida—to no avail. There have never been any demands for ransom but tips still come in almost every week. “Some callers have been pestering us and the FBI for years, one of them since 2013. Some are very strange,” Amore says Anthony. “One man recently insisted that JFK Jr and his wife were the thieves and faked their deaths to commit the crime.”

“There are two kinds of tips,” Kelly says. “There are people who have a theory on who was involved in the theft. We check it out. Sometimes it isn’t easy because the suspect might be dead or we will interview a suspect and he denies it,” Kelly says. Investigators can only apply so much pressure to get information, because the statute of limitations to prosecute the theft as a crime expired in March 1995. So suspects are told about the potential for immunity from other legal prosecution and the $10m reward offered by the museum. “Then there are the people who are convinced—they are very specific, that they know where the art is.”

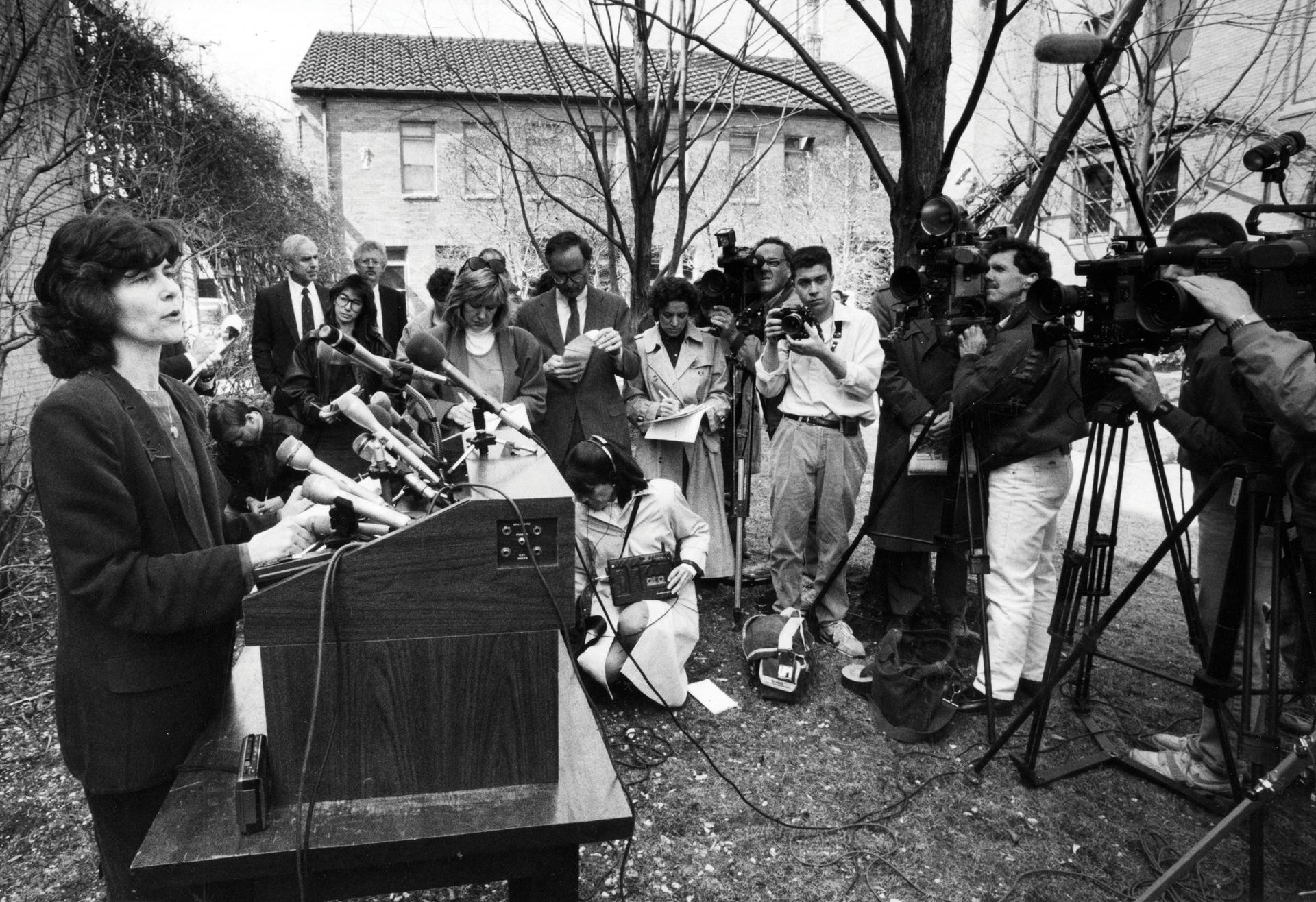

Anne Hawley, the director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston at the time, answers questions at a news conference in the garden after the 1990 robbery Photo by Tom Landers/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Not long ago, a man told Kelly he had developed technology that could recover the paintings. He then showed Kelly two divining rods and brought him to a street in south Boston. “The man put on headphones, the rods came together and he said the paintings were in a nine-story office building a block away,” Kelly says. “I told him I couldn’t get a warrant for the entire building based on what he told me. I’ll investigate any viable theory but there comes a time when enough is enough.”

If Gentile told us everything he knows, we’d be further along on our recovery efforts

Among those investigated by Kelly and Amore is Robert Gentile, 82, a former mobster suspected of concealing secrets about the theft, who was released from prison last March after serving four years for three gun and drug cases. He insists that he knows nothing about the theft and that he was “framed” by the widow of a mob associate, who said her husband gave Gentile two of the stolen works in around 2000.

The FBI has searched Gentile’s house in Manchester, Connecticut, three times in the last decade with dozens of agents, ground-penetrating radar and K-9 dog units. They found guns, drugs, five gun silencers, $20,000 stuffed in a grandfather’s clock, police hats, badges and a list of the stolen Gardner works with possible black market prices. “If Gentile told us everything he knows, we’d be further along on our recovery efforts,” Kelly says.

“I believe that some of the paintings have changed hands several times over the years. It’s also quite possible that some people have those paintings and don’t know what they have,” Kelly says. “We are confident we know who committed the crime. We believe they don’t still have the art. We don’t know if the art is all together or was split up.”

Other top investigators who have weighed in on the theft disagree about where the works are now held. Robert Wittman, the former head of the FBI’s art crime team says some of the paintings could have ended up in Corsica.

An Eagle Finial: Insignia of the First Regiment of Grenadiers of Foot of Napoleon's Imperial Guard (1813-14), after Antoine-Denis Chaudet Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

In 2006, when Wittman was still with the FBI, he posed as an unscrupulous art dealer who had clients interested in buying the Gardner paintings. He met two thugs from Corsica who indicated that the Vermeer and one of the Rembrandts were held by a gang there. The operation turned up nothing in the end, Wittman says, “because of bureaucratic difficulties and turf fighting”. But an officer of the French national police agreed with his theory. “Why would the thieves steal a Napoleonic finial instead of another painting?” Wittman says, referring to the gilded bronze eagle decoration also stolen along with the Master paintings. “Because Napoleon was from Corsica.”

The paintings are in Ireland, behind a wall in West Dublin

Charlie Hill, formerly of Scotland Yard’s Art and Antiques Squad, disagrees. “Although Napoleon was from Corsica, the paintings are in Ireland, behind a wall in West Dublin rather than in the US, behind a wall in South Philly.” He declined to elaborate, however.

Kelly and Amore said that they have no evidence that the paintings are in Corsica or Ireland. The FBI believes that in the years after the heist, some of the art was taken to Philadelphia “where it was offered for sale by those responsible for the theft”.

Amore has created an extensive database on his computer that lists every person the investigators have contacted over the years. “I enter every piece of information about every person of interest we’ve heard about,” he says. “I stopped counting but there are at least 30,000 different pieces of information—addresses, phone numbers, vehicle information, biographical data, places of employment. It helps us when I get a new phone call and saves a lot of time.”

Many visitors to the Gardner museum spend time looking at the empty frames that held the stolen paintings and still hang on the walls, but not everyone is interested in seeing them. “I’ve talked to people who used to come here as students,” Amore says, “but they haven’t come back because, to them, the theft is so sad.”