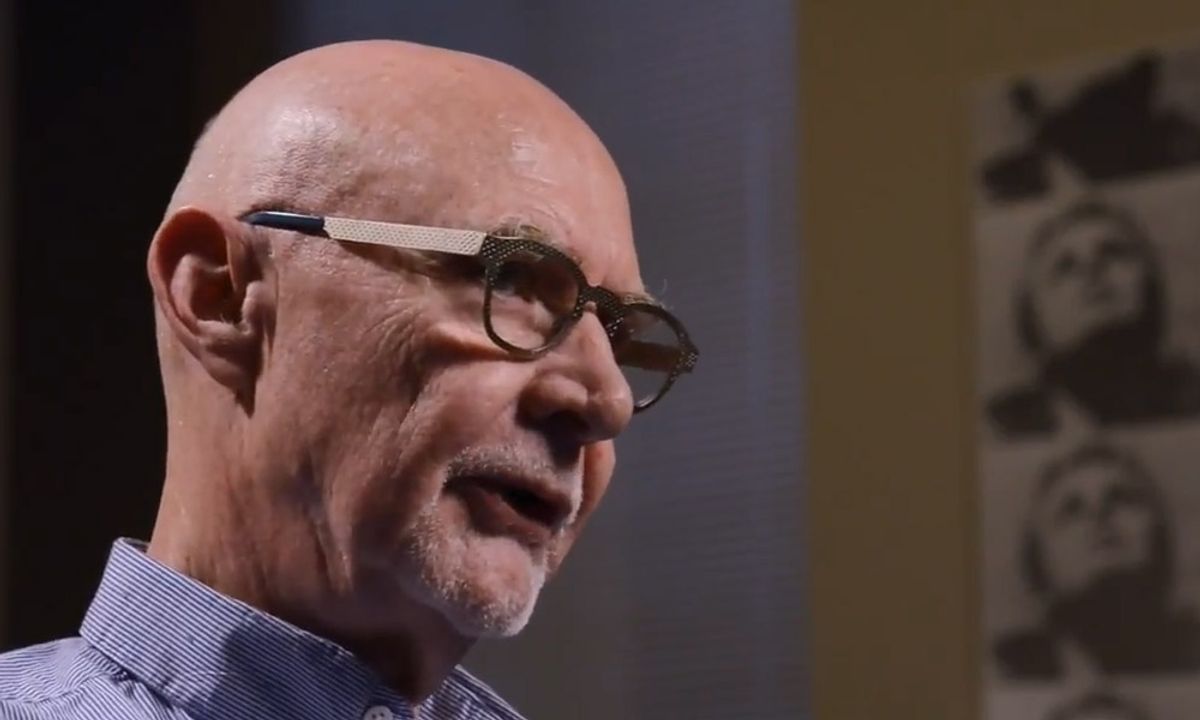

The influential US writer, editor and curator Douglas Crimp died in New York on 5 July, aged 74. Crimp was a key figure in defining postmodern art in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly with his exhibition Pictures, and his writings on the role of photography and appropriation and forms of “institutional critique”, where artists subvert museums from within. He was also a member of Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power), the activist group that took on the US government’s ignorance and mismanagement of the Aids crisis from the 1980s, making major contributions to documenting the effects of the crisis and promoting artist activism.

As he recounted in his recent memoir Before Pictures, Crimp was born in Idaho, studied art history in New Orleans and arrived in New York in the late 1960s. He worked briefly as a curatorial assistant at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and taught at the School of Visual Arts before enrolling in 1976 at the Graduate Center at City University of New York, where he entered the orbit of Rosalind Krauss, the co-founder of the MIT Press journal October. He quickly became a member of the magazine’s editorial team.

Crimp’s most celebrated work in art historical terms was the Pictures exhibition, held at the small New York gallery Artists Space in 1977. Little seen at the time, the show featured the artists Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo and Philip Smith and was accompanied by Crimp’s essay on their work in relation to poststructuralist theory. He expanded it in 1979 for October and this latter, better known, version crucially included Cindy Sherman. The essay defined “a group of younger artists [that] sees representation as an inescapable part of our ability to grasp the world around us”, and its influence was so great that those artists, and others working in a similar field like Richard Prince, became known as the Pictures Generation.

Crimp was a provocative thinker throughout his career, not least in the 1981 essay The End of Painting, also published in October, which savaged the romantic institutional revival of painting in the US and Europe just as it was gathering pace. This reflected his unwavering commitment to what he described in the text as “those art practices of the sixties and seventies which abandoned painting and coherently placed in question the ideological supports of painting, and the ideology which painting, in turn, supports”—photography, conceptual art, performance, film and video and installation art. MIT Press’s anthology of Crimp’s writings, On the Museum’s Ruins, includes many of his thoughts on those disciplines and media, while his 2012 book Our Kind of Movie discusses Andy Warhol’s films. At the time of his death, he was compiling a collection of his texts on dance and film for Dancing Foxes Press.

Crimp’s work on Aids was arguably as significant as Pictures. An issue of October he edited in 1987—Aids: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism—remains a landmark in Aids literature. In it, Crimp called for a “critical, theoretical, activist alternative to the personal, elegiac expressions that appeared to dominate the art-world response to Aids”. Meanwhile, Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on Aids and Queer Politics (2002) anthologised his own writings on the subject, documenting how he came to see that for many in the gay community affected by Aids, “mourning becomes militancy”, and exploring what he saw as a complacency in queer politics that followed Act Up’s radicalism.

Crimp remained a prolific writer, an occasional curator and, as professor in art history and visual and cultural studies at the University of Rochester in New York, an esteemed teacher up until his death.