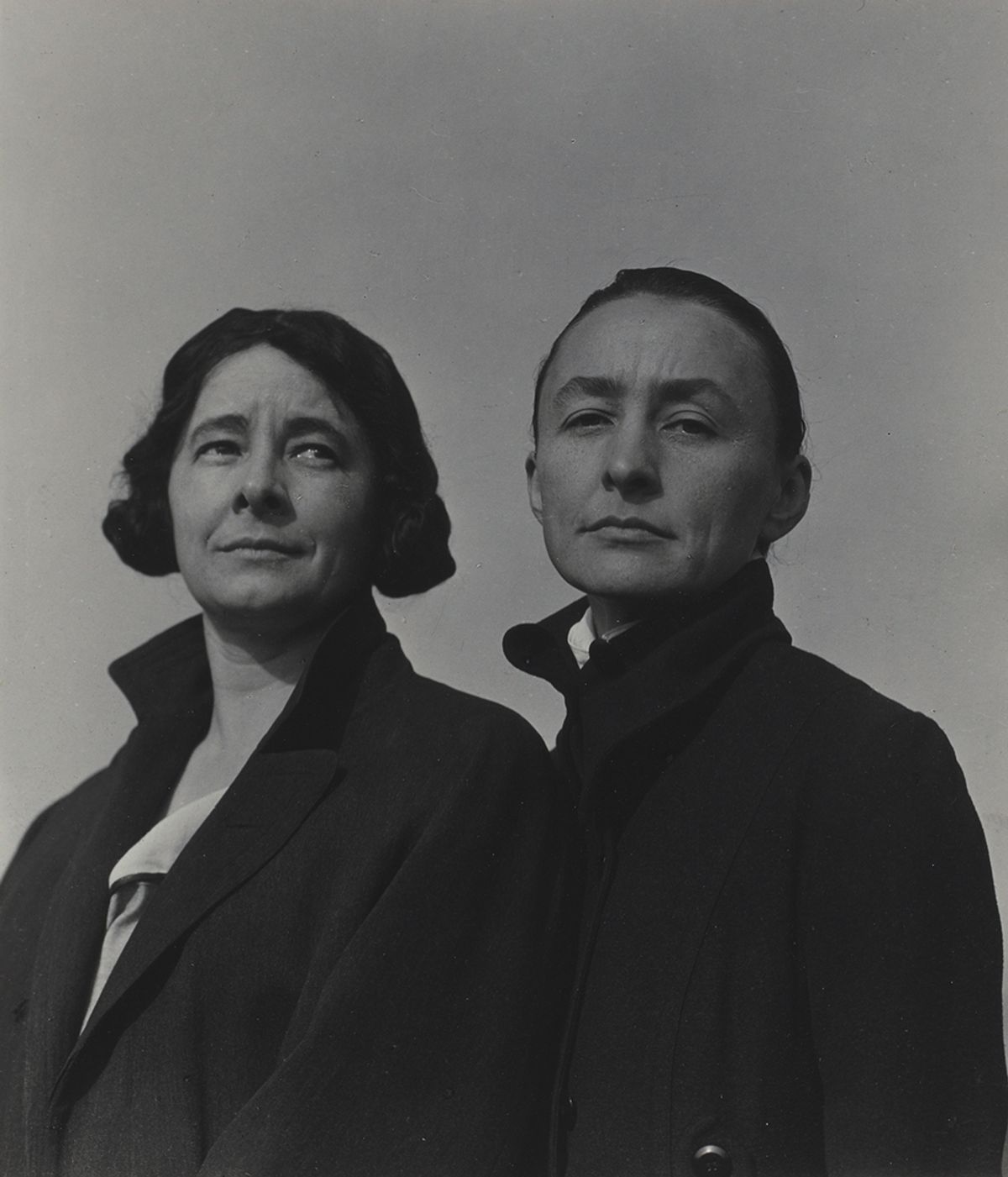

Georgia O’Keeffe is often celebrated as a modernist pathfinder who paved the way for female artists. But the exhibition Ida O'Keeffe: Escaping Georgia's Shadow (until 6 October) at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts shows how she blocked her younger sisters Ida and Catherine when they followed her example.

Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow introduces this little-known artist—and tarnishes her elder sibling’s lustrous mythology. On view are 25 works by Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, who signed her works Ida Ten Eyck, along with eight photographs by Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe’s mentor, dealer and husband from 1924 to 1946.

Ida, born in 1889 and two years younger than Georgia, began painting in oil in 1925, in her mid-30s. Works by Ida and her younger sister Catherine were featured in a 1927 group show in New York curated by Georgia. Ida signed hers “Ida Ten Eyck”. In 1931 and 1932, Ida produced a series of paintings inspired by the Highland Lighthouse in Truro on Cape Cod. The works, composed with a bracing confidence and drama, blend familiar forms with geometric abstraction. The gestural paintings also took a cerebral approach to light and structure. Ida would move to pure abstraction with the work Creation in 1936.

Ida O'Keeffe, Variation on a Lighthouse Theme IV (around 1931-32) Jeri L. Wolfson Collection

Getting there was a bumpy road. While Georgia O’Keeffe had flourished under the guidance of Stieglitz, who brought her from remote Texas to New York in 1918, the younger Ida and Catherine, two of the five O’Keeffe sisters, were stymied by the deaths of their parents and an extreme lack of funds. Ida earned an art certificate at the University of Virginia in 1917, and taught in that region. Frustrated as she sought permanent work, she turned to nursing, graduating from Mt. Sinai in New York in 1921.

Yet Ida continued to draw and study art. Thanks to Georgia, she also saw much of Stieglitz, who flirted with her at his summer home on Lake George. The much older man called himself “Crow Feather” and Ida was “Red Apple”—the suggestive “Black Ferns” was another of his nickname for Ida. The Clark exhibition includes a 1924 photograph that Stieglitz made for her of an upright feather plunged into an apple beneath it.

If that image did not make the point, Stieglitz wrote to Ida, with playful and forward ardour: “Old Crow’s Feather may have yet to become a man—to show that Gallants are still alive & know their duties to a Lady, particularly one with fiery burning seeking challenging eyes—with healthy skin—& body filled with bursting maleward giving—with breasts that challenge God himself to do his duty by them…”

Despite organising the 1927 show with Catherine and Ida’s work, Georgia, under treatment for a nervous breakdown, demanded in 1933 that her sisters stop exhibiting. Catherine complied for the rest of her life, but not Ida, who became estranged from Georgia. After that, Ida’s existence was itinerant—as art teacher and nurse, and as a factory worker for Douglas Aircraft in the Second World War. She died in poverty in Whittier, California in 1961, supported begrudgingly at the end of her life by her sisters Georgia and Claudia. Works that she left behind were auctioned off quietly in 1985.

“It’s definitely one of those ‘if only or ‘what if’ sort of situations,” says the exhibition's curator Sue Canterbury, who started exploring Ida’s work after seeing one of her paintings in a private Dallas collection, and wrote most of the catalogue.

After the New York Times mentioned Canterbury’s Ida project in 2014, it gained momentum, taking on aspects of a crowdfunding campaign and the Antiques Roadshow as Canterbury dug works out of oblivion. One eventual lender, Neil Lane, the jewellery designer for the television show The Bachelor, had bought a Northland Lighthouse painting at a flea market in Glendale, California. “A lot of the owners of these [works in the exhibition] weren’t collectors per se. This whole museum experience was completely new ground for them,” Canterbury says.

If the public now knows about Ida O’Keeffe, it has also learned more about her celebrated sister. “She wasn’t particularly supportive of other women artists,” said Canterbury, “it speaks to Georgia’s insecurities, in spite of her fame at that time.”

As more of Ida’s paintings turn up, so do new facts. Three works were destroyed in the Paradise, California, fires last November, just as the show was premiering at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Since then, scholars have also learned that Georgia was not alone in obstructing Ida’s career. Canterbury found an interview with the artist and curator Gordon Gilkey (1912-2000), who studied printmaking with Ida in the late 1930s. He stated that Stieglitz convinced a dealer in New York not to exhibit Ida’s work.

But researchers might not find that information in the Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive at Yale University.

“Georgia had a lot of time to edit Stieglitz’s papers, and if there was anything that she didn’t like, she had carte blanche to get rid of it,” says Canterbury, who suggests that one of Georgia O’Keeffe’s goals in editing Stieglitz’s papers was to strengthen her brand by minimising evidence of his crucial influence. “If Stieglitz had not brought her to New York, would we know who Georgia O’Keeffe was? No,” she says.

Purging Ida from the record could have been another goal. Canterbury says letters between Ida and Stieglitz end between 1932 and 1938. “I find it mysterious that there’s an absolute stop in the correspondence. I cannot prove it, but I suspect that [Georgia] may have edited things out,” she says.

With the current exhibition, the record stands corrected, Canterbury says. “It’s about rediscovering this woman who was edited out of history.”