At Auschwitz, more than two million visitors each year will learn about the Nazi guards who perpetrated some of the greatest atrocities known to man, and of the people who perished as a result. However, less is told from the perspective of the survivors. The exhibition Through the Lens of Faith: Auschwitz, which opens today outside the death camp’s main gate, aims to shift that emphasis.

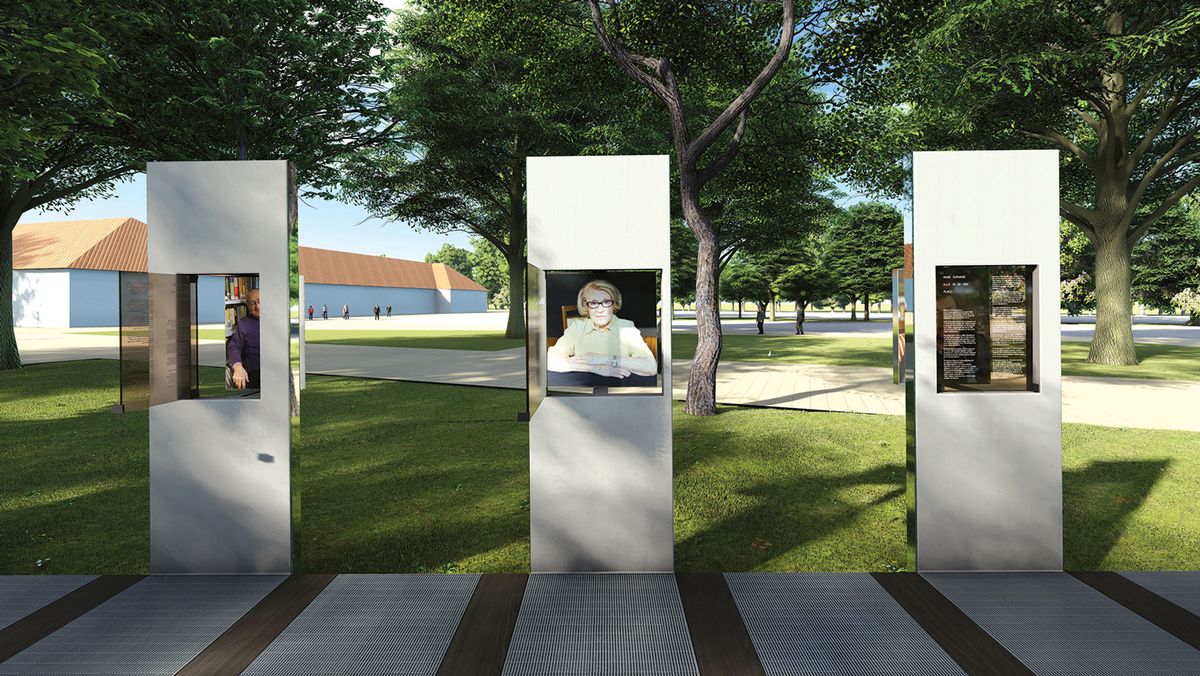

In an open-air structure designed by the architect Daniel Libeskind, the installation presents 21 large-scale colour photographs of survivors by Caryl Englander, along with excerpts of interviews in which they give testimony to both the brutality experienced there and how their faith kept them resilient. “Auschwitz is about what was done to the Jews,” says Henri Lustiger-Thaler, chief curator of the Amud Aish Memorial Museum in Brooklyn, which has produced and installed the exhibition, hosted by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum through the end of 2020. “What we talk about is how the Jews responded. It’s a paradigm shift.”

The concept for the exhibit grew out of Lustiger-Thaler’s work with Auschwitz’s docent training programme to integrate stories of the subterranean life of observant Jews into the guides’ tours. “I think there’s a lot of bias against looking at religious comportment as a theme to be investigated,” says Lustiger-Thaler. Counter to the presumption that many Jews lost their belief in God in the face of atrocities, Lustiger-Thaler has found that daily faith-based practices persisted at the camp. In the new installation, he has foregrounded how prisoners secretly performed morning prayers, celebrated Jewish holidays and sought counsel from rabbis.

“Looking back, as a religious man, I ask myself today how did I live through this?” reads the testimony of Irving Roth, who was 14 when taken to Auschwitz. “I decided my quarrel was not with God but with man… Faith was the only thing left.”

Englander, who is the chair of the board of the International Center of Photography in New York, subverted the conventions of sombre survivor portraits and chose to photograph her subjects joyously, in colour, and in their home environments. “They feel they survived for a reason,” says Englander, who was raised in an Orthodox Jewish home herself. “A few of the people admitted to us they didn’t tell their stories when they got out. They started to feel judged or ashamed” by others questioning how they could have remained religious.

The interviews and photoshoots took place in Toronto, New York, Poland, Israel and Germany with 18 Jewish, one Romani and two Polish Catholic survivors between the ages of 80 and 102. All will be collected in a book, published by Phaidon in September. “We’re living in a time when you have the decline of the survivor population and the incremental rise of anti-Semitism,” says Lustiger-Thaler. He went through extensive negotiations with the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, which does not allow installations on hallowed ground, to get authorisation to display it outside the gate.

Concerns over DNA remains beyond the gate meant Libeskind’s structure could not pierce the ground. Set at a 45-degree angle to the main road, it rests on top of the grass and leads towards the woods. “These people survived,” Lustiger-Thaler says. “This is about life in the shadow of a death world.”