The steep terraces on the lawn of Dunshay Manor are the clue to the life's work of its last private owner, the sculptor Mary Spencer Watson. Just restored as the Landmark Trust’s 201st property, the ancient stone house folds into Dorset farmland and stands within sight of the spectacular ruins of Corfe Castle.

On Tudor maps Dunshay is shown surrounded by quarries for prized Purbeck building stone and the house itself stands on quarried-out seams which supplied marble to Salisbury cathedral. In the 20th century, the quarries provided raw material and inspiration for Spencer Watson, whose monumental pieces can be found appropriately in the cathedral and many churches, schools and private collections. A major retrospective in Salisbury in 2004 came two years before her death aged 92.

Aerial view of Dunshay Manor © Landmark Trust

The 16th-century farmhouse was gentrified in the 17th century and rescued from near dereliction through an Arts and Crafts rebuild around 1900. It then became the beautiful home of two artists, the sculptor and her father, the portrait painter George Spencer Watson. Its barn also staged extraordinary avant-garde performances created by her mother Hilda—for which her daughter was conscripted to perform and make props, costumes and scenery. Invitations to a heady mix of Ancient Greek myths and English nursery rhymes in a style heavily influenced by the costumes and choreography of the Ballets Russes came with the promise of lavish tea on the lawn. Beautiful images of Mary and Hilda, including several in the National Portrait Gallery, by the photographer Helen Muspratt who was a family friend, preserve the startling quality of the productions. Many found them to be hard work— the Landmark Trust historian Caroline Stanford has uncovered files of letters from guests struggling to wriggle out of a second invitation.

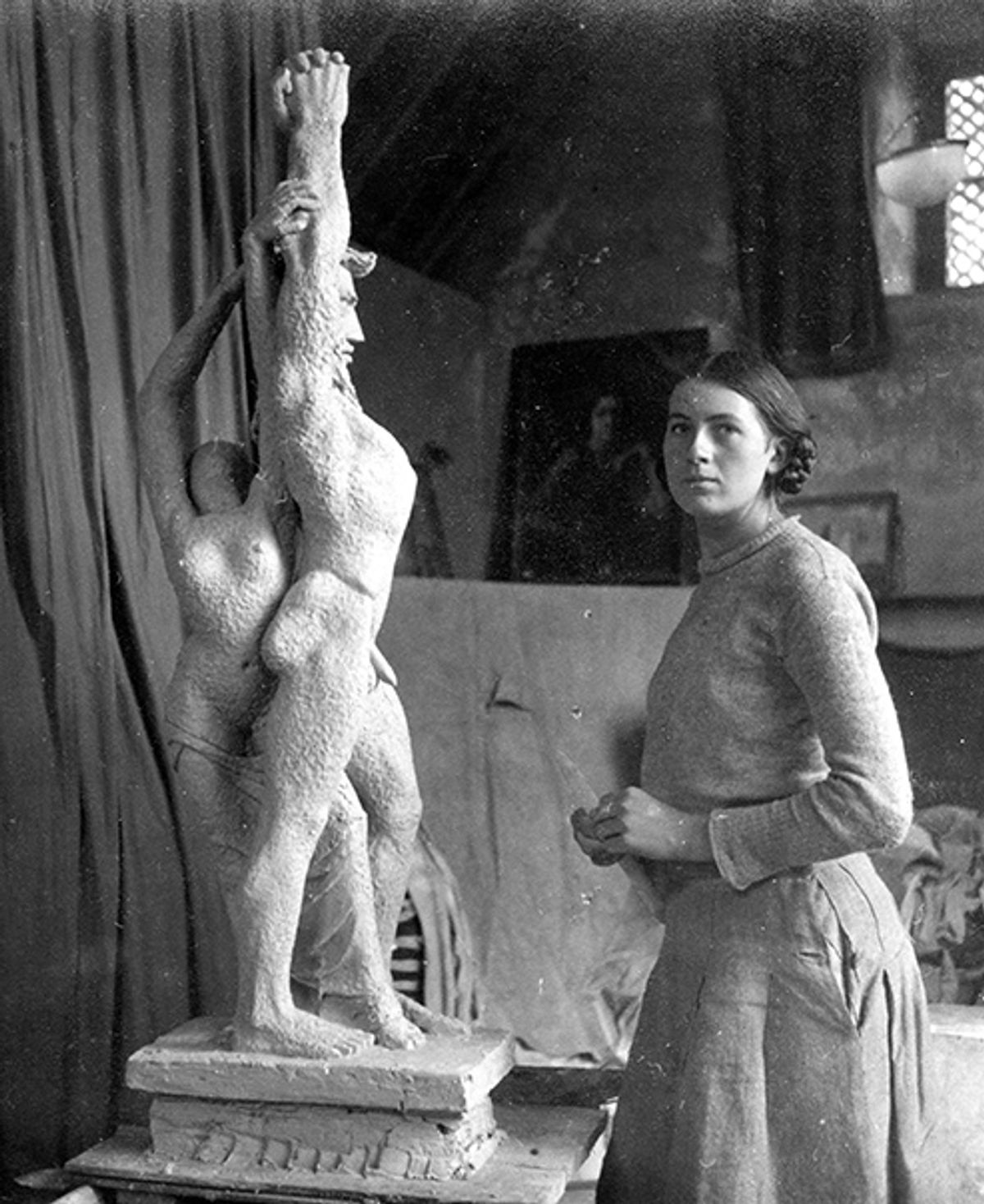

The latest restoration returns the silvery stone house to its 1920s appearance, when the family bought what became Spencer Watson’s base throughout her long life. In a Dorset County Magazine interview in the 1980s, she recalled local stone cutters still working entirely by hand, apart from a donkey turning a capstan. They loaned the nine-year-old girl a set of tools, gave her a lump of stone and got her started. She went on to art college in Bournemouth at 16 and studied in London and Paris, training in direct carving from artists including John Skeaping, but always returning to Dunshay.

Spencer Watson chose to bequeath Dunshay to the Landmark Trust to preserve its history. Stanford met her there when the house and garden were still full of her work and her father’s, including Four Loves (1922), his painting of his wife, daughter, horse and dog on a windswept Dorset clifftop. She recalls that “she looked like a little old lady, but still had a formidable personality.”

George Spencer Watson's Four Loves (1922) Courtesy Christie's

Reproductions and an exhibition in the former dairy now tell the story of both artists, but the house was stripped after her death in a bitter dispute fought out in the courts, to the dismay of the Landmark Trust whose inheritance was upheld but at a great cost. Works of art which Spencer Watson wished to see preserved in the house were scattered at auctions, but the Landmark Trust still hopes to acquire or borrow and bring back some of the original works.

The court cases also exposed a discreet lesbian love affair lasting more than half a century, which began when Margot Baynes, her husband and young family moved into Dunshay as tenants after the death of Spencer Watson’s parents. The Baynes marriage ended in divorce several years after what Stanford describes as a “coup de foudre” when the two women met.

She was buried under a beautifully cut stone at nearby Langton Matravers. The house, like all Landmark Trust properties, is now open for year round lettings. It is also open free to visitors in September, as part of Heritage Open Days.