How to commemorate a life cut tragically short? An exemplary example is offered by Birmingham's Ikon. The gallery has just opened an exhibition dedicated to the memory of Michael Stanley, who was a curator at Ikon before becoming director of Milton Keynes Gallery and then Modern Art Oxford before his sudden death in 2012.

The Aerodrome is loosely structured around from Rex Warner’s eponymous allegorical 1941 novel, a favourite book of Stanley’s, and is co-curated by two of his artist friends, George Shaw and David Austen. Stanley’s myriad interests—political, literary, philosophical and artistic—and the range and quality of the artists he worked with make this a rich, multilayered exhibition that offers many entry points.

The first room contains three works that each in their own way offer a form of memento mori. There’s a Constable cloud study of 1822 from Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum; Anya Gallaccio’s Preserve Beauty (1991-2019), in which densely-packed fresh gerberas are sandwiched behind three sheets of glass and left to decay over time; and, especially poignantly, Chair Falling, a looped Super-8 film that shows an empty chair repeatedly falling and breaking made by a twenty year old Stanley for his Ruskin School of Art degree show in 1995.

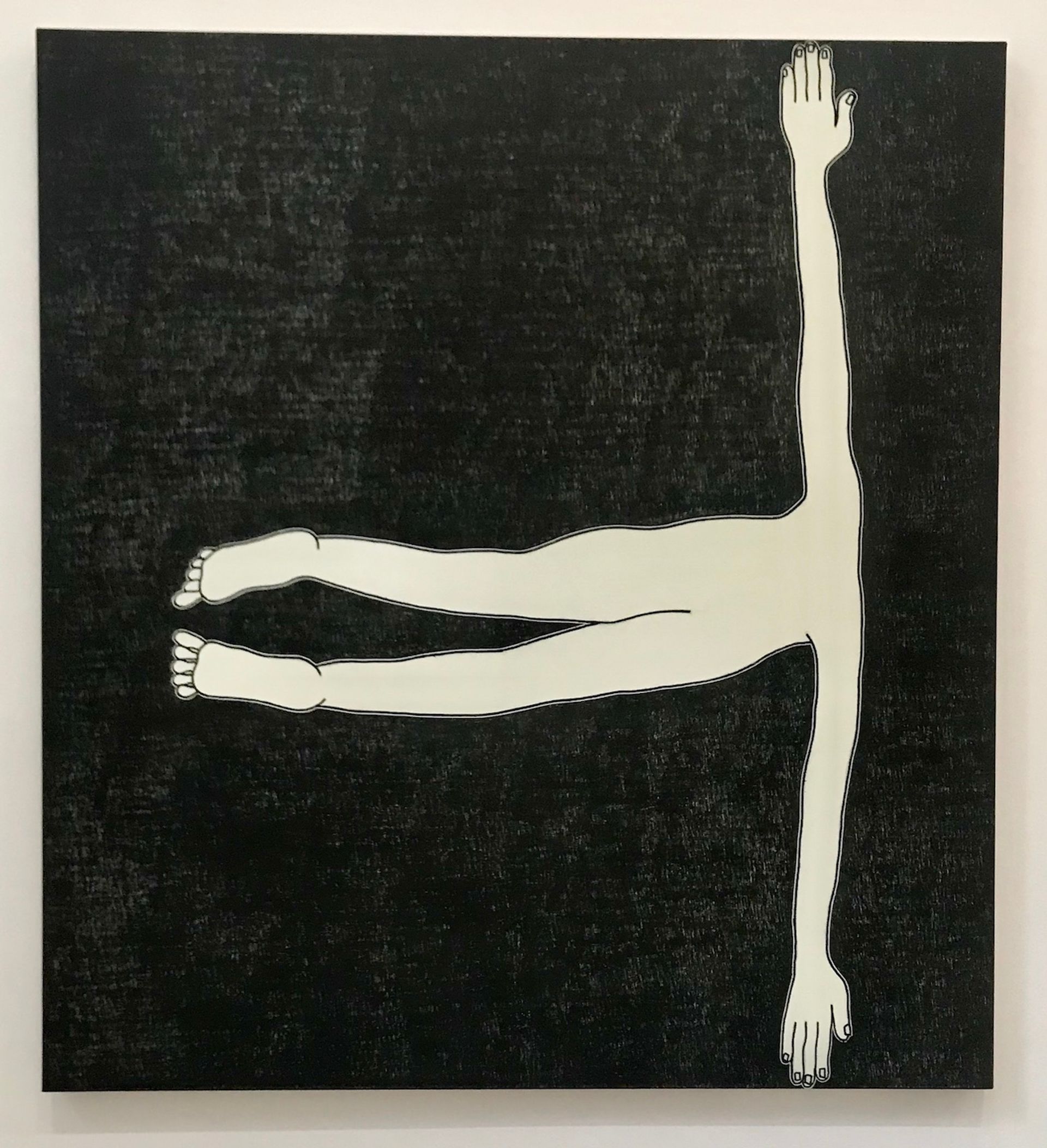

David Austen, Fallen Man, 2013 Louisa Buck

Each of the forty nine artists selected has a particular relevance to Stanley, yet the show is more than a parade of favoured works. It also coheres as an arresting, thought provoking show in its own right with conversations and connections running throughout. A counterpoint to Constable’s clouds is Michael Saistorfer’s oppressive pungent black Cloudscape made from inflated industrial inner tyre tubes which had its first showing at MAO and now dangles from the ceiling of the Ikon’s entrance lobby. Langlands & Bell are showing animations of swirling three letter airport acronyms while Austen’s painting of Fallen Man tumbles like Icarus into an abyss. In a room devoted to dysfunctional machines, Roger Hiorns clogs a Vauxhall engine with encrustations of turquoise copper sulphate crystals and Siobhaun Hapaska scales up and converts a Roman Catholic altar lamp into a flashing hazard warning.

As in Warner’s book, here the countryside is also no easy idyll. Nature is skewed in Richard Woods’ cartoonish wood grain cladding as well as in Graham Sutherland’s 1940’s painting of a bristling cornstook and Marcus Coates’ film of a Chelsea football supporter, delivering his chants like a raucous bird of prey as he strides through leafy woodland. A particular highlight is Adrian Paci’s beautiful and disquieting 2006 film of children—including Stanley’s—that uses the reflection of mirrors to charge an oh-so English landscape with magic and mystery. It is a film infused with a quiet sense of absence and loss, and these elegiac feelings are also conjured up by Cathy Wilkes’ cabinet of mundane relics as well as in Elizabeth Magill’s painting of a dark blue glowing expanse of empty motorway and Polly Applebaum’s two crumpled white sheets before which hang two beads on near invisible threads, suspended in space.

Linder, Salt Shrine, 1997-2019 Louisa Buck

This is a show that is as much about celebration as commemoration and both these aspects come together in one of the most dramatic of exhibits: Linder’s Salt Shrine which fills a small side gallery with several tons of salt. The work was initially made for Stanley’s first officially curated show in his old school building in Widnes in 1997. So enticing was its dune-like expanse of billowing white that, on the opening day and with Linder’s blessing, two of Stanley’s children clambered onto the surface and jumped around, christening both the work and the exhibition in a way that their most gregarious and welcoming father would have undoubtedly approved of.