The Los Angeles-based artist and activist Andrea Bowers jokingly bills herself as a “second-wave feminist stalker”, and her #MeToo-inspired installation in Art Basel’s Unlimited section is clearly rooted within the feminist tradition of confrontational confessions, like those of Barbara Kruger, Judy Chicago and Martha Rosler.

Comprised of more than 200 photographic prints in nine shades of red that detail allegations of, and responses to, sexual harassment and abuse, each of these stories has come to light as a result of the social media movement that went viral in the wake of the revelations of sexual misconduct by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. Titled Open Secret I and II, it is the second iteration of a project started back in 2017 to archive what Bowers deems to be one of the most significant feminist actions in her lifetime, to tackle systemic inequities of power. Since its unveiling in Basel, one of the installation’s panels was removed after a woman whose image was featured in the piece said she had not given permission for it to be used by the artist. Its removal has prompted questions on social media about the morality of creating a public work about the personal pain of individuals. We speak to Bowers about visualising violence, the pervasiveness of patriarchy and the ethics of activism.

The Art Newspaper: Open Secret is based on the myriad sexual misconduct allegations coming to light. How and with whom did you build this database?

Andrea Bowers: It began with a Google Doc when the #MeToo movement was picking up speed two-and-a-half years ago, after the news came out about Harvey Weinstein. I started making an archive of each sexual harassment accusation to help visualise what this violence looks like. I work with a team of writers, designers, editors and artists—Kate Alexandrite, Angel Alvarado, Ryan Beal, Carey Coleman, David Burch, Miriam Katz, Zut Lorz, Julie Sadowski, Ian Trout, Ingrid von Sydow—to catalogue this information. This is about research, writing and documenting what is a very important feminist movement—one that, as of now, we have yet to fully understand how it will shape the future.

Each entry includes the name of the accused, their job, the allegation against them, an image, and the statement made by the accused, printed in their original font to give a sense of their tone. Some responses are contrite, others are flat-out denials; most fall between the two and are some sort of non-apology that absolves the accused of wrongdoing. Me and my team then offer a summary and analysis of these materials.

Where I take the most creative licence is with the images—that’s where my subjectivity is, choosing the photograph that needs to illustrate these testimonies is an abstract process. I can’t be certain there aren’t innocent people accused. I’m just bearing witness to the documentation. But I’m also responding to it and working through all this pain – that of the accused and my own.

You first exhibited the piece last year at Capitain Petzel in Berlin. Has the work changed and grown with time for this iteration at Art Basel?

On a straightforward level, it’s bigger. There are now more than 400 entries [in the database, and not all will be on view. The size of it is important in order to envision the ubiquitousness of harassment and violence. My own relationship to it has changed, too. The first year was emotionally traumatising. I was so angry working through the first batch that I would find myself screaming at dinner parties. I had to deal with my trauma and that of my team—we’re of different [sexual] orientations, races. How to express all these pains adequately? The language is what has changed the most. We used the word victim in the first set; now we use survivor. We also stopped using the word actress and now use actor. This second set is much more nuanced in that way.

That brings up an important question about the #MeToo movement as a whole. Since it started, some feminists have felt that it simply is not inclusive enough in scope to be useful in dismantling patriarchal power systems that put people at risk of exploitation and abuse. Do you have frustrations with the movement?

Embedded in this project is an analysis of the #MeToo movement itself. The way women of colour or less famous women are not being acknowledged. Class is a huge part of it that isn’t discussed as often as it needs to be. The movement itself is not perfect, even if it has been hugely helpful—this kind of violence is inherent in patriarchy, and it’s the first time we’re really calling it out. But we can’t boycott everything that hasn’t addressed power and patriarchy adequately or fully. That doesn’t mean the movement failed. It’s not the movement’s fault that we are suddenly aware of this issue and are figuring it out as we go. And it’s not the movement’s job to figure out, it’s ours. Open Secret is my way of figuring it out and trying to help others figure it out.

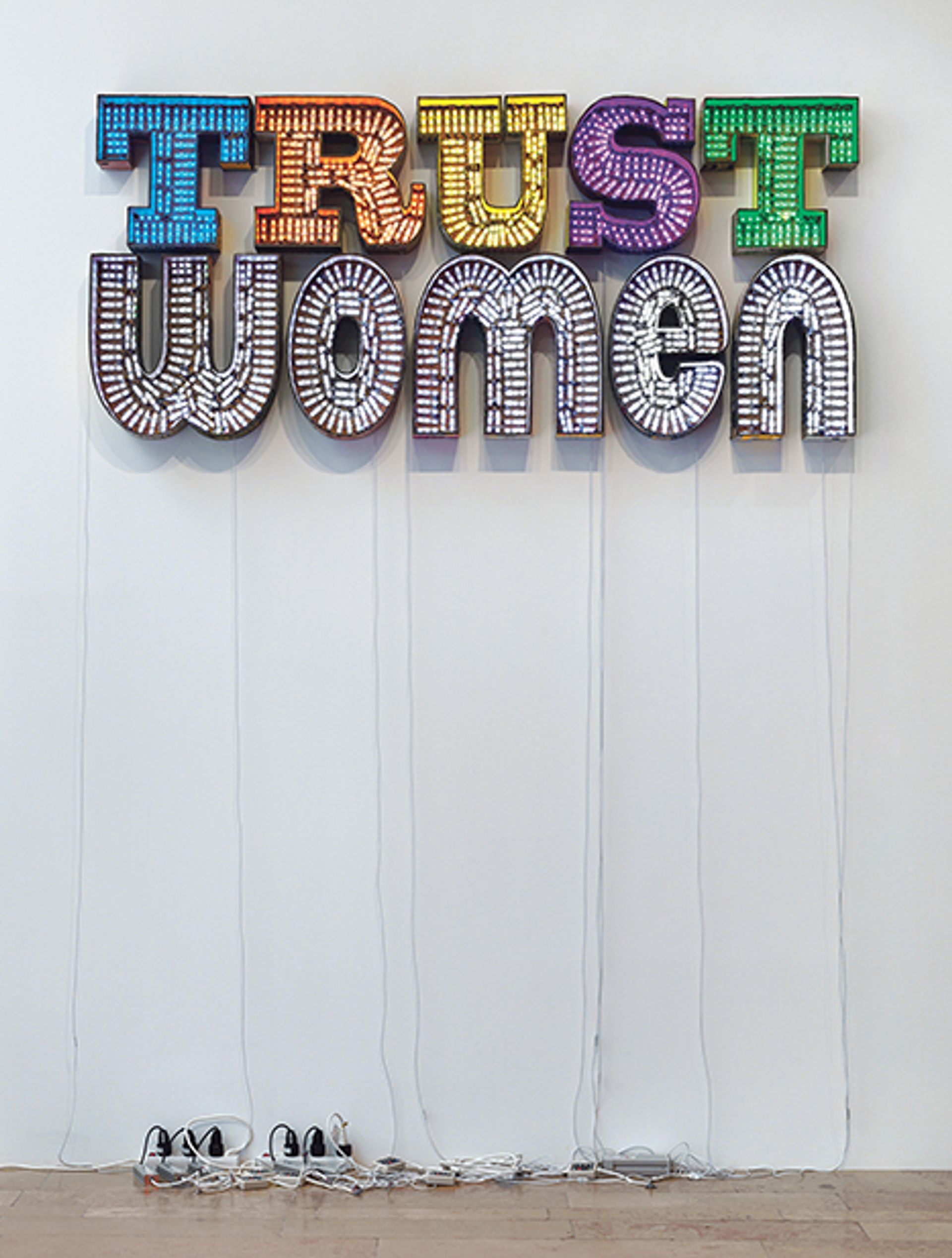

Andrea Bowers's Trust Women (2018) © The artist. Photo credit: Jens Ziehe

A lot of your work is politically blunt and has a public service-oriented quality to it. Does activism change in a commercial art fair setting?

Socially engaged projects are convivial, but they are not always about social justice. They are not necessarily politically engaged. But this project is, even though I am not working directly with activists. I was lucky to work with [artist] Suzanne Lacy at [Los Angeles’s] Otis College of Art and Design years ago, where so much of what we call social practice now was defined. And no, it just doesn’t fit into a commercial setting if you’re doing it well. Thankfully, I have gallerists who are committed to getting this kind of work out there, even though it’s not really saleable. I also try to give a portion of any proceeds back to charities and activist networks so that the issue doesn’t become monetised.

What are some of the ethical concerns when dealing with public issues of such a personal nature?

I didn’t want to cause more pain to the people who went public with their stories. Sometimes they want to be anonymous and I try to preserve that. We’re at a point where one group sees this kind of violent behaviour as normal, [and the other] as harmful. This isn’t specific to a gender—both women and men experience it. This entire issue is not just about their personal pain; that’s not why they came forward. They came forward because they are asking for all of us to pay attention to patterns of abuse of power. That’s what I’m trying to capture by analysing these stories.

What are you hoping people take away from the work at Art Basel?

I don’t think Europe is dealing with these issues in the way the US is. I think it’s largely an American conversation right now, but I think—I hope—it will spread. We’ve normalised these violent behaviours for too long, and for that reason I think we need to honour #MeToo for being something monumental. So many of these testimonies can get swept away in the chatter of the 24/7 news cycle. Art is slow—for that reason it helps us remember. It creates a visual history. I want the work to sculpturally embody this huge uprising, I want people to feel its urgency. Living with these kinds of secrets eats away at you—it might be hard to look at them, but it’s much harder to live with them.