Five weeks ago, the Swiss-Icelandic artist Christoph Büchel unveiled a dilapidated fishing boat at the Venice Biennale. This rusting vessel has a tragic story: it is the place where hundreds of migrants drowned on the night of 18 April 2015 while attempting to reach Europe from Libya. The Italian navy later recovered 458 corpses from the locked hull of this doomed ship; hundreds more are thought to be still missing at sea. But none of this information is provided in explanatory text near Büchel’s display. For reasons known only to himself (Büchel does not do interviews), the artist has chosen to show the boat, now entitled Barca Nostra, as a work of art devoid of all context.

“I think it’s a missed opportunity… Art should raise awareness and fill in the gaps in people’s knowledge. That’s my idea of art being effective,” says Federica Mazzara, a senior lecturer at the University of Westminster who researches art about migration. She is the co-curator of Sink without trace, an exhibition opening in London today which tells the stories of migrant deaths at sea which has been organised with the British artist Maya Ramsay.

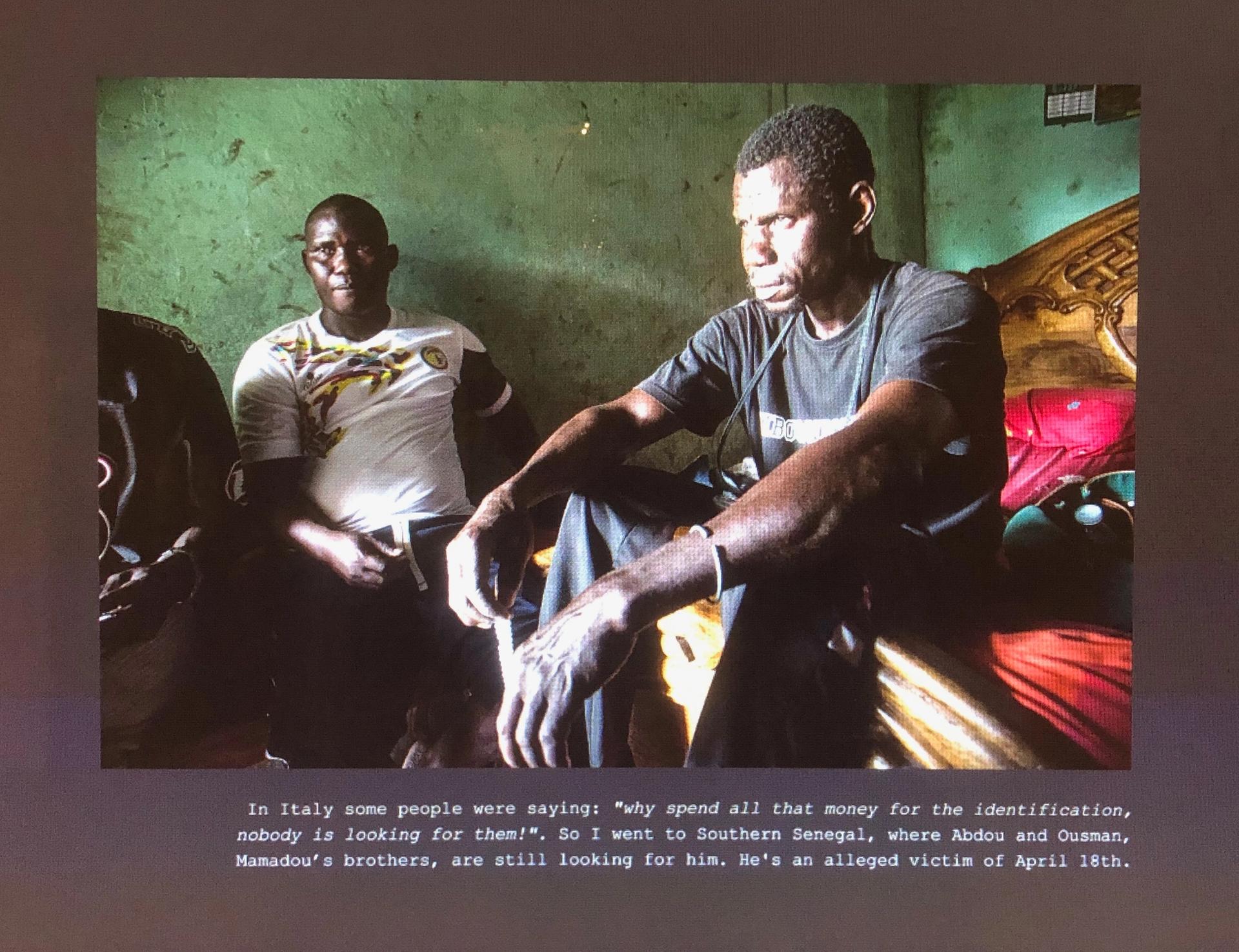

These men are still searching for their brother who probably drowned on board the boat now on display in Venice. Still from Max Hirzel’s Migrant Bodies, 2015-17 Cristina Ruiz

Crucially, their show includes the work of several artists who are themselves refugees and have first-hand knowledge of the perilous journeys to Europe that so often end in tragedy. One of them is the Kurdish artist Behjat Omer Abdulla who first came to Britain as a refugee from Iraqi Kurdistan and is now based in Sweden. Included in the exhibition are two giant, black-and-white portraits of young brothers depicted by Abdulla with their eyes closed. The drawings, entitled Head of Child I (From a Distance) and Head of Child II (From a Distance), both 2016, are based on a story which “was being retold around Swedish refugee camps,” the artist writes in the exhibition catalogue. “Under the fear of war, as thousands of families fled their homelands, a mother of twin infants started her journey to seek a safer place.” She probably came from the Middle East or Asia, Abdulla writes, and eventually ended up “crossing the deadliest route to Europe over the Mediterranean Sea by boat.” Then, tragedy struck.

Behjat Omer Abdulla, Head of Child I (From a Distance) and Head of Child II (From a Distance), both 2016 Cristina Ruiz

“During the harsh physical struggle of the journey, the mother lost one of her twin infants. Despite the loss, she kept the dead child with her for days on the boat. As tensions rose, the smugglers tried to force the mother to throw the body of her child into the sea. She refused and kept the body with her. One night, while the mother was sleeping, the smugglers took action. The mother woke to realise that her living child was missing and that she had been left with the dead child. The smugglers had mistakenly thrown the sleeping twin into the sea.”

In-depth investigations

Others whose work is included in the show have embarked on serious, in-depth investigations of migrant stories, including Max Hirzel, a photojournalist based in Italy, who documented the immense forensic effort to identify the 458 bodies recovered from the fishing vessel which Christoph Büchel has now appropriated as a work of art. In 2016, Hirzel travelled to the Nato base of Melilli in Sicily where medical specialists meticulously examined the recovered corpses and the personal belongings found alongside them. Hirzel’s photographs of this six-month effort are woven together in the video Migrant Bodies, 2015-2017, which also includes images related to other disasters at sea.

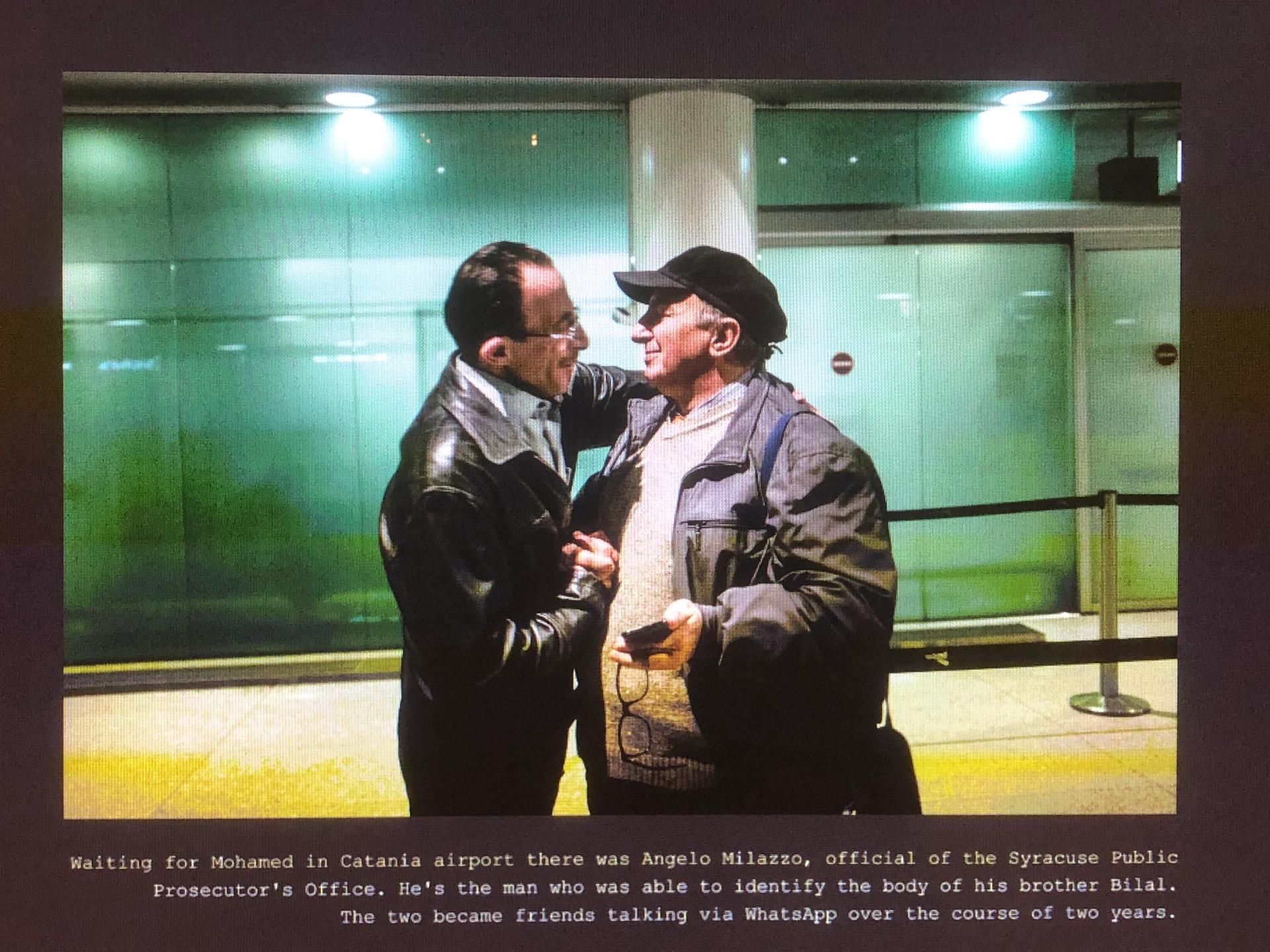

Hirzel also travelled to Senegal to meet Abdou and Ousman, who are still searching for their brother Mamadou who is believed to be one of the victims of the April 2015 shipwreck. He met and photographed Mohamed Motak, a Syrian lawyer who travelled to Sicily to visit the grave of his brother Bilal and recover his belongings. Bilal died aboard another boat which sank in the Mediterranean on 24 August 2014; his body was later identified by Angelo Milazzo, an official of the Syracuse Public Prosecutor’s Office. One of Hirzel’s photographs shows the emotional first meeting between Motak and Milazzo at Catania airport.

The Syrian lawyer Mohamed Motak meets the man who identified the corpse of his brother Bilal. Still from Max Hirzel’s Migrant Bodies, 2015-17 Cristina Ruiz

Another immense investigative effort into a migrant sea disaster was undertaken by Forensic Oceanography, a research project set up by the film directors Lorenzo Pezzani and Charles Heller, which is allied with the multi-disciplinary group Forensic Architecture. Liquid Traces: the left-to-die boat case, 2014, is a film which tells the story of a small rubber boat which left Libya in March 2011 with 72 passengers on board. Just one day later, the boat ran out of fuel and was left to drift in the Mediterranean for 14 days as the migrants slowly succumbed to dehydration and death. By combining the testimonies of survivors with wind and sea data, satellite imagery and mobile-phone location information, the film reveals that numerous military, commercial, and shipping vessels could have helped the drifting migrants but chose not to. Instead, the boat was left to drift back to the Libyan shore. By the time it reached land again, 63 migrants had died.

Still from Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen’s End of Dreams film, 2016

Other exhibitors have chosen to tackle the subject of migrant deaths at sea with more artistic responses. During a residency in Italy, the Danish artist Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen made 48 concrete sculptures which each resemble a body wrapped in canvas (End of Dreams, 2014-2016). The plan was to submerge these off the coast of Calabria in Southern Italy so that they could each acquire a patina of sea organisms and then remove them from the water and exhibit them as a group. But a violent storm engulfed the raft which was holding them in place and the sculptures were scattered across the seabed. Only 14 of these were eventually found by the artist. A film about the project shows the concrete body bags lying at the bottom of the sea in silent testimony to the thousands of migrant bodies lost in the Mediterranean.