The South African artist William Kentridge works at the smallest, and the grandest, of scales. He always begins with drawing. Sometimes he animates and films his drawings, and then, through workshops with musicians, dancers, singers, designers and composers, he transforms them into elaborate, immersive works: multiscreen videos or exuberant live performances such as The Head & the Load, seen last year in London and New York, which tells the story of African soldiers in the First World War. A survey of his work is at the Kunstmuseum Basel while another opens in Cape Town in August.

The Art Newspaper: Tell us about your new work for Basel.

William Kentridge: Over the past ten years, I’ve been making short films called Drawing Lessons, most of which involve me interrogating myself. They began as a test to see if I can ever discover anything new in this process. The piece for Basel is another in this series. It’s called Learning from the Old Masters because it’s shown in the Basel Kunstmuseum among works by Kurt Schwitters, Picasso, Cranach and Grünewald. It also has to do with the presence in Basel of Desiderius Erasmus, the 15th-century humanist thinker. It’s a series of questions that get half-answered. What is a contemporary artist doing among these Old Masters? The one persona—myself—on one side of the table, says, “You have no right to be here”, and the other replies in the Latin of Erasmus, thereby answering the scepticism of the first person.

Self-interrogation is a consistent element of your work—you’re often in your pieces. Why?

For anyone who has ever written anything, or drawn anything, or recorded themselves speaking or singing, there’s an enormous difference to one’s sense of self in the moment of making and when you take a step back to become the viewer. As you’re writing, every sentence feels fine. When you’re drawing every line seems necessary. When you’re singing, it sounds great. And when you step back, you are always disappointed. What seemed like such good writing the night before, when you re-read it the next morning, you say: “I couldn’t have written anything so stupid, some other idiot did it.” And you curse yourself. That shifting between yourself as the maker and yourself as the viewer is something that is very obvious in the studio, but it is often less painfully obvious in the rest of your life. So that’s one of the ways in which the things that are natural in the studio often serve to make things that are invisible in daily life very present. And I suppose with the Drawing Lessons and a lot of my work, that is the aim.

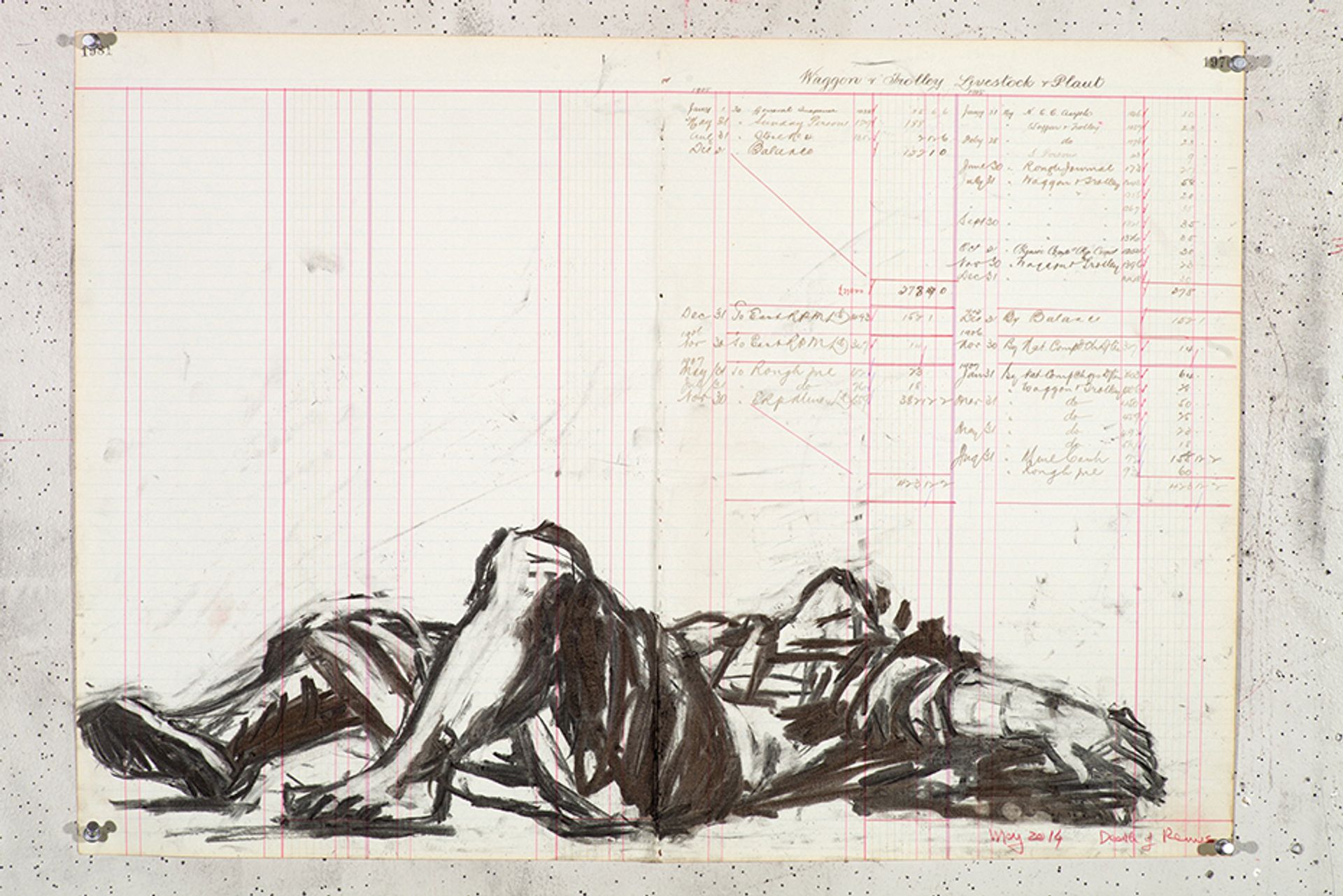

William Kentridge's Dead Remus (2014-16) © The artist; Photo: Thys Dullaart

The show includes some of your earliest work, like your set designs for Sophiatown. Tell us about that.

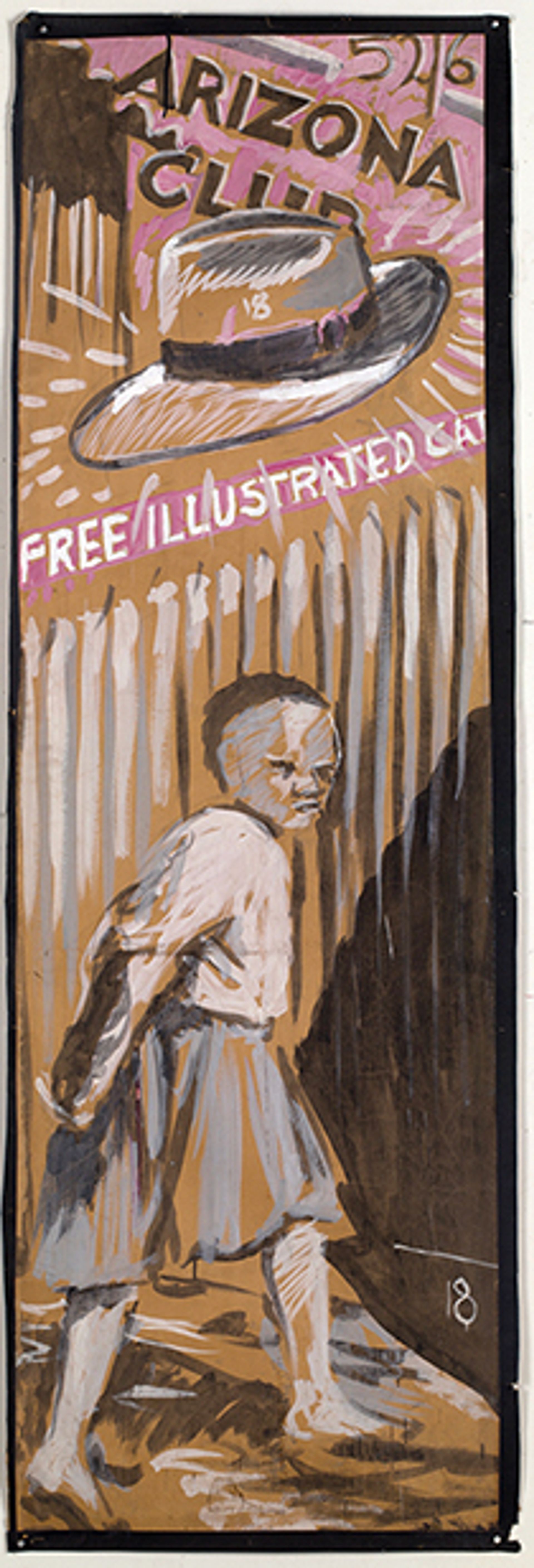

This was a play made by the Junction Avenue Theatre Company, which was a non-racial theatre company in Johannesburg in the 1980s and 90s, at a time when this was very rare. It was a place for improvisations and white and black actors meeting and finding points of contact. It was always an imperfect meeting of people from backgrounds of privilege and people who were in difficult conditions in the townships. But over the years a number of wonderful pieces of theatre were made and one of them, directed by Malcolm Purkey, was Sophiatown, the story of a freehold suburb of Johannesburg open to black owners, which during the 1950s was declared a white area and demolished. The residents were sent to Soweto and [the new white suburb created in Johannesburg] was called Triumph: the play was about this. I painted the sets—a series of gouache paintings on brown paper. They’re halfway between paintings, very crude ones, and simply a scenic backdrop.

Both your parents were prominent Anti-Apartheid lawyers: your father Sidney defended Nelson Mandela and other members of the ANC in the late 50s during their treason trial. Later, he represented the family of Stephen Biko during the inquest into his death. Did they galvanise you at an early age?

My mother’s rage at the government and at particular judges who carried out its actions was very palpable for a lot of my childhood. My father’s anger was very different; it was there but it was much more held in, measured. It would come out at times in court. I had this understanding of what South Africa was from a very young age, and also a sense that the law profession had been done [in my family]. I was never going to match what my parents had achieved. I needed to find something different, which became as different as it could be: drawing on the walls.

William Kentridge's Drawing for Sophiatown (1998) © The artist

Were your parents supportive of your artistic endeavours?

They were very supportive. My father always said: “Why on earth would you do law if you could do anything else?” At the time it was a relief to feel there was never pressure to be a lawyer and always a lot of support for me in the years of not knowing what I was doing, and then in the years of being an artist. My father was also sceptical about art, but that scepticism is not a bad thing to have hovering at the edge of your activity.

You’ve stayed in the same neighbourhood in South Africa your entire life. Why?

In many ways, Johannesburg is a terrible city, so the fact that I’m still there after 64 years must mean there is something strong holding me. Inertia is part of it, but it’s not enough. It can’t only be family because most of my family is in London. It has to do with what it is to work on the margins, but it also has to do with South Africa feeling like a premonition of the rest of the world; the relationship of a small formal economy and an ever-growing informal economy seems to be the way that a lot of things happen in the world, where you’re constantly aware of the provisionality of every moment, how the world can change. Whereas there’s a great anomie to say, “Let me just be part of the international art world and live in Berlin or London or New York.” It’s certainly not impossible, and in many ways would be much more pleasant, but there’s a sense of disassociation, of floating above the world.

Do you believe artists have a responsibility to be political?

No. The only hope of them to be responsible politically is to not have that sitting on top of them as a pressure. I think it was Gabriel García Márquez who said that the artist’s political responsibility is to write well. To undertake the activity with care, energy and an openness to what will arrive and, in the end, the art will show who you are.

• For the full interview with William Kentridge, listen to the next episode of The Art Newspaper Weekly podcast on 14 June

• William Kentridge: a Poem That Is Not Our Own, Kunstmuseum Basel, until 13 October

• Premiere Artist Talk: William Kentridge, 12 June, 10-11.30am, Hall 1 auditorium, Messeplatz