During the preview days of the Venice Biennale last month, Switzerland’s boarded-up pavilion in the Giardini had the air of a nightclub. A queue of VIPs snaked out of the nondescript door to the exhibition of the Berlin-based artist duo Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, Moving Backwards. The resemblance was not accidental: Boudry and Lorenz describe their pavilion installation as an “abstract club”, and its centrepiece is a film showing five glamorous, gender-fluid dancers cutting loose on a black lacquered stage. The central motif of moving backwards—which the dancers on screen perform quite literally—is both a reference to regressive politics and a proposed route to freedom. In a newspaper handed out to visitors, the artists lament the anti-immigration measures taken by European governments and the rise of hate speech, but they also evoke the inspirational story of female Kurdish guerrilla fighters wearing their shoes backwards to evade enemies in the mountain snow. “We are up for turning disadvantage into a tool,” they write. “Let’s collectively move backwards.” Here, they tell us more about collaborating with activists, shaking up viewers’ expectations and making room for fantasy.

The Art Newspaper: How did you discover that female Kurdish guerrilla fighters wore their shoes backwards as a survival technique? What resonated with you about the “tactical ambivalence of this movement”, as you write in your letter to visitors of the Swiss pavilion?

Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz: We came across the story through close friends and oral history. We have been attentive to the recent women’s revolution in Rojava and the inspiring Kurdish women’s movement. When we heard about this survival technique, we immediately thought it should become the starting point for our project.

Witnessing the political backlashes in terms of gender, sexual rights or the rights of refugees, and the general feeling of being forced to move backwards, we wanted to think of strategies of resistance. This is why we suggested “moving backwards”, but in the way that the Kurdish women did: it seems they are moving backwards, because their shoes leave traces in one direction in the snow. But actually, they are moving forwards.

In the film, we further complicate the idea: the performers move backwards or walk forwards while wearing their shoes backwards. Parts of the dances were reversed, and the performers learned to dance them that way. We reversed other parts of the film digitally, but in a subtle way, which requires attention to notice. Conceptually, we like to undermine the idea of flawless progress in the social as well as in the economic realm, and the idea that we always know what the right direction is.

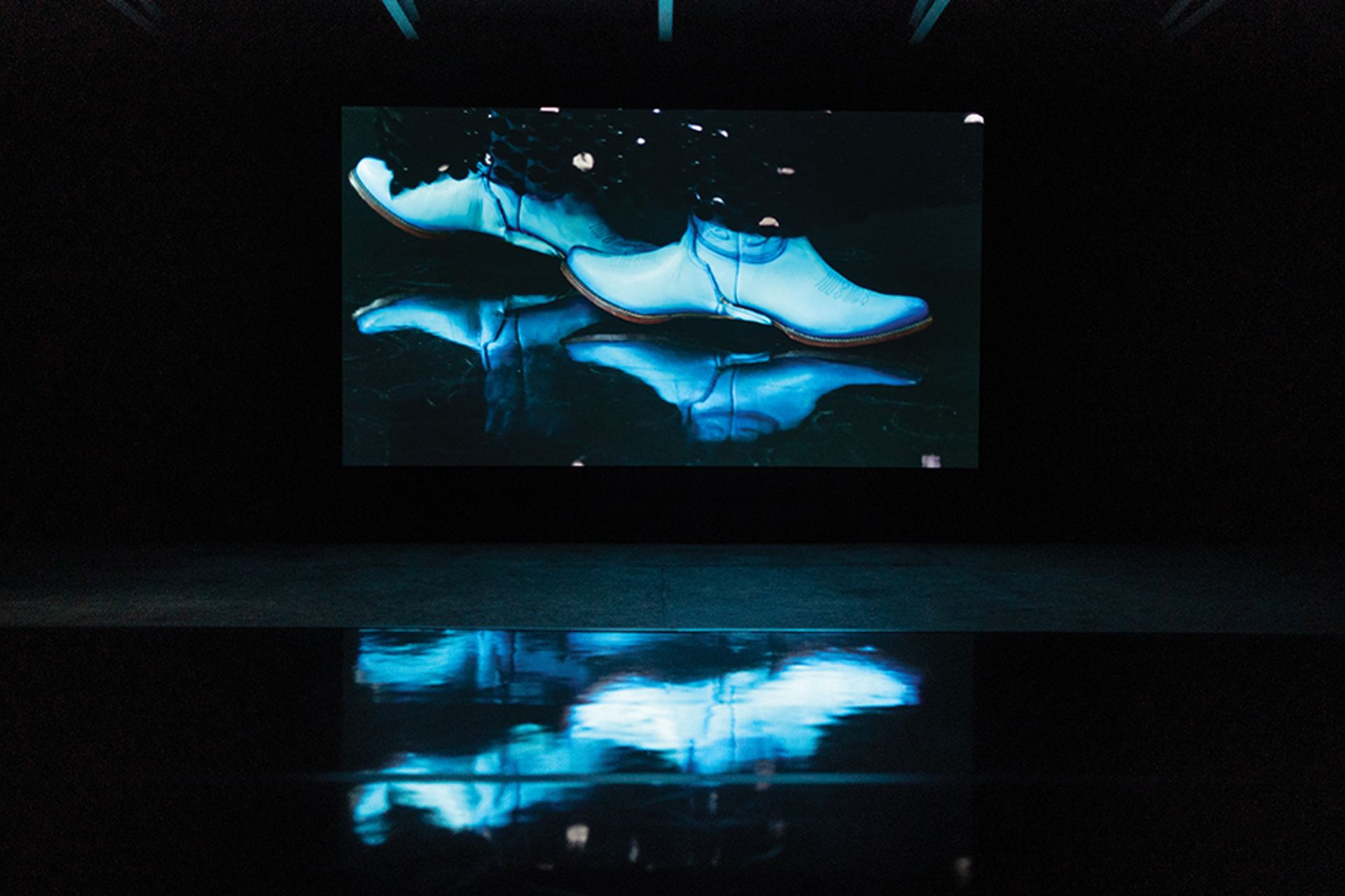

The centrepiece of the presentation is a film featuring five gender-fluid dancers cutting loose on a black lacquered stage © Annik Wetter; courtesy of the artists

The performers in your previous films embody specific historical figures, such as Kathy Acker and Jean Genet. You have described the practice of uniting different time periods as “temporal drag”. How has that evolved in Moving Backwards, and why?

The idea of temporal drag is precisely not to ask performers to “embody” historic figures, but to stage encounters between a performer and remnants of a past moment, like one of Genet’s texts or interviews. In Toxic (2012), Werner Hirsch in female drag re-speaks a TV interview that Genet gave to the BBC, for instance, without trying to “be” Genet. We are interested in the co-presence of different temporalities, and of opening up a past moment that was not properly lived or actualised in the past, to give it another try. That’s not so different from the backward movements, where one usage of the concept could be to step back and try again, with more force or with more pleasure.

You work with artists you admire rather than casting actors. How did you assemble the performers for this film?

Werner Hirsch and Latifa Laâbissi approached us; Werner had already performed in many of our films, while we exchanged documentation with Latifa and felt there was a close relationship between our works. Marbles Jumbo Radio had previously worked with our friend Andrea Geyer and we admired their dance style. We started rehearsing with Marbles in New York and developed some of the basic movements together. We didn’t know Nach and Julie beforehand, but we had seen Julie performing fantastically with the Michael Clark Company and were smitten with Nach’s fierce Krump dance when she was introduced to us. They all brought in parts of their choreographic work and it was our task to facilitate an encounter between the different approaches and choose the ways that movements might support and complicate our concept. Most importantly, we choreograph the relationship between the camera/the viewer’s gaze and the performances.

The film is only one part of a theatrical “abstract club” environment that transforms the Swiss pavilion. What inspires you about the nightclub?

The Swiss pavilion has a strong architecture which is elegant but very 1950s. In the past, the architecture sometimes took too much importance, while some aspects of it didn’t receive much attention at all. We used the winter covers of the garden—industrial grey panels—to cover up the entrance and make the architecture disappear. Instead, it looks like the entrance of a club. We built a black pathway to bring the audience—literally moving backwards—directly on to a wide stage that we have created for the “painting hall”, the main room of the pavilion. The audience watches the film from the very stage where it was shot, meaning they are in the position of participating in a possible future performance. Another pathway leads them behind a large structure that resembles a bar, putting them in the position of a barkeeper. Trompe l’oeil paintings on the bar show the bars and clubs we like in Berlin, where we met lovers and friends. The pavilion garden, which has often been neglected in the past, becomes a meeting point or a place to read the newspaper. We speak of an “abstract” club since we don’t mean to mimic a club. Rather, we want to conjure up images of a place where a variety of encounters might happen, where lights, sounds and objects might take over, where we let loose and allow fantasies to go wild.

Visitors assume the position of performers by entering the pavilion on stage. Do you see the public as performative participants in the work?

The work is very much about the relationship to the audience. We like to choreograph the audience as we want to avoid easy ways of getting an overview and arriving at categories too fast. We like to challenge the position of the viewer and produce some kind of insecurity and sense of the unexpected. In his essay about the film, André Lepecki writes that the clapperboard at the end is almost a signal to the audience to start their own performance now. We like that very much.

Moving Backwards mixes female Kurdish guerrilla techniques with urban dance and elements of underground culture © Pro Helvetia/Keystone/Gaetan Bally

What prompted the idea of the newspaper with letters to the audience, involving so many collaborators from around the world?

It is important for us to show that our ideas cross-reference other people’s thoughts, creations and activism. Going through the letters it becomes clear that something is starting to build, what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak calls a “planetary” perspective. The concept of moving backwards resonates with different contexts, which makes it so much deeper and more interesting. We also like that the formats of writing are so diverse, from a score to a poem, from conceptual writing to an academic text.

You have both worked together since 2007. What does it mean to make art as a duo? Does this affect your creative process? If so, how?

We always liked the idea of being more than one. We regularly work with Werner Hirsch whose other personas are Henri Fleur, Antonia Baehr and Agnès B. We have long-time collaborators for all the stages of producing a work. Renate comes from a theatre performance background and Pauline has played in different bands, so the concept of collaborative work has always been part of our practice. The two of us share all the roles and tasks of production.

• Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz’s Moving Backwards is being shown in the Swiss pavilion at the Venice Biennale until 24 November. The exhibition catalogue is published by Skira. For more information, visit www.movingbackwards.ch