With a major retrospective coming up at New York’s Met Breuer next year (4 March-5 July), plus his Seascapes at the Guggenheim Bilbao (until 9 September), the German artist Gerhard Richter is having another moment. At Art Basel this week, his work is on show at the booths of David Zwirner and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, among others.

This is hardly a surprise: Richter is widely regarded as the world’s most important living painter and remains active despite his 87 years, if less prolific than in the past.

His body of work, which spans nearly six decades, has evolved over time, as he explores manifold ways of representing the world around him. This varies from the early blurred black-and-white paintings interrogating Germany’s attitudes to its own history, to landscapes, portraits, colour charts and what are probably the best-known and most expensive of his works, large-scale abstracts. These have become ultimate trophy pieces—inoffensive, colourful, easy to live with, and probably an asset class all their own.

Indeed, analysis by the team that maintains Richter’s website shows that in 2018, only 14% by value of his works offered at auction were bought in.

Collectors & Prices

Abstraktes Bild sold for a record £5.8m at Sotheby's London in 2015 © 2013 Gerhard Richter - All rights reserved / Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

The Richter market is global, says Cheyenne Westphal, the chairwoman of Phillips: “Buyers come from around the world–[there’s] a lot of interest for the abstracts from Asian buyers.”

One who has a number of large-scale pieces is Pierre Chen, the Taiwanese electronics billionaire. Lily Safra, the Brazilian billionaire, bought and donated another large abstract to the Israel Museum in 2012, while veteran rock star Eric Clapton sold three between 2012 and 2016 at huge mark-ups on the prices he originally paid.

In 2015 the Chicago financier Ken Griffin set the world auction record for Richter at Sotheby’s London, when he bought the 1986 Abstraktes Bild for £35.8m ($46.3m).

Other abstracts have sold for between $28m and $34m, and represent nine of his top ten prices. But these were almost all set between 2012 and 2017, and such heights have not been reached since 2018.

“Since 2016 we have seen fewer of these works, and if the works offered are not AAA grade, they don’t achieve those extraordinary price levels,” Westphal says. She notes that the surface of the abstracts is very important, saying that a ruptured surface with visible layers, with shiny oils and a dramatic use of colour, make a work much more desirable. The use of red, almost inevitably, tends to increase value as well.

In March this year, Phillips made a strong £15.5m ($20m) for the 1963 image of a jet fighter, Düsenjäger, which came with a difficult back story: it had been bought in 2015 by a Chinese guarantor, who had defaulted after buying it for $24m.

However, last year saw a number of failures at auction, notably Schädel (Skull, 1983), which sold for a relatively low £11.5m (around $15m) at Christie’s London.

At the other end of the scale from these colossal prices, Richter has produced many giclée prints, and the availability of these editions means that buyers can start collecting at very low price points: under €1,000 for some offset prints of popular subjects such as his Seascapes.

From there to the $20m+ paintings, there are all price levels: Gagosian London has shown secondary market works—overpainted photographs (1989-2016), tagged at $80,000 to $100,000; in May Christie’s sold a 1981 abstract painting for $915,000 with fees—notably under its $800,000 to $1.2m presale estimate, which does not include fees.

Growth

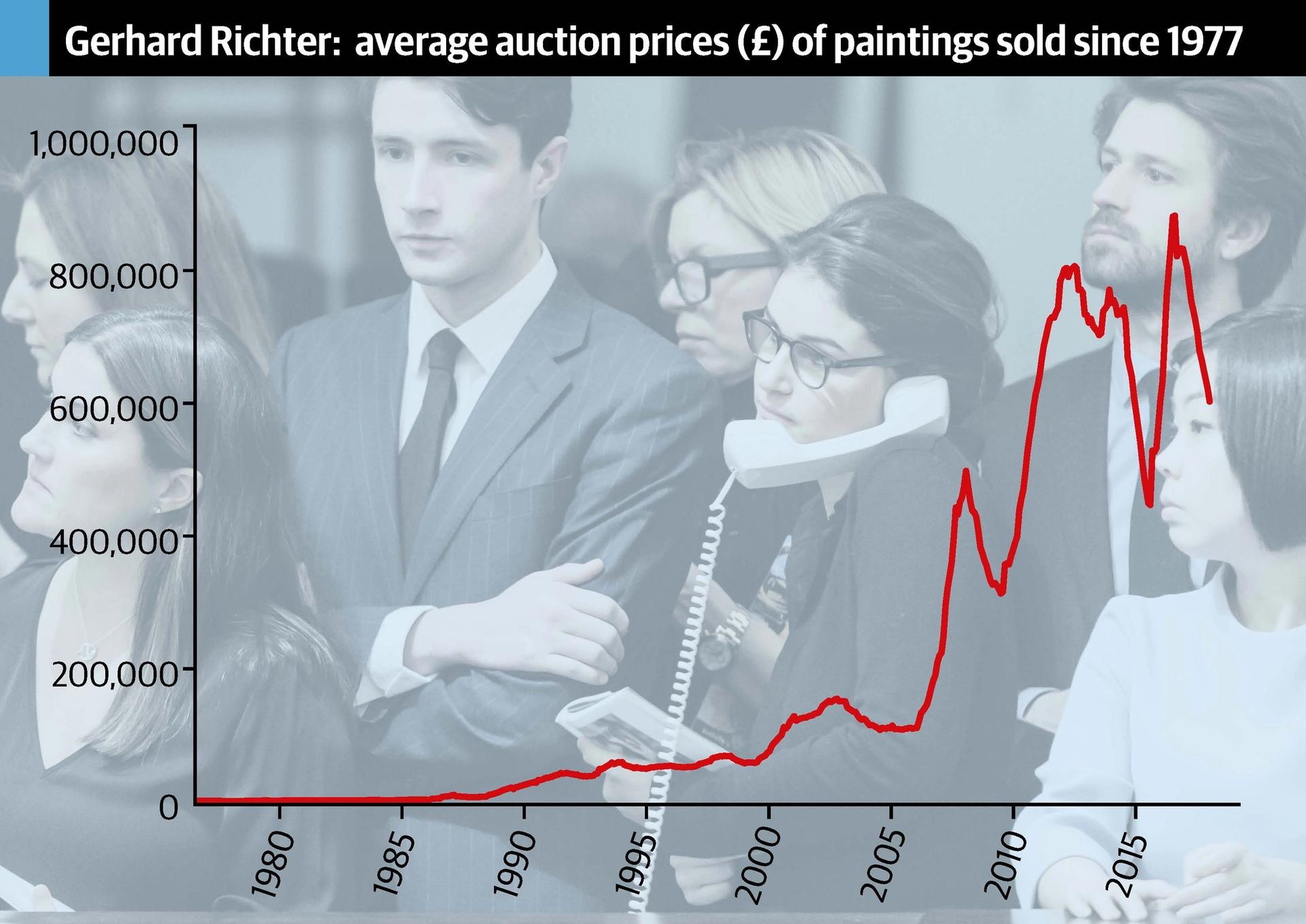

Auction data for Richter’s paintings gathered by Art Market Research excludes the top and bottom 10% of results. © Art Market Research

Price charts compiled by Art Market Research show the extraordinary growth in the value of paintings since 2000—an astonishing 64,076% change since 1977, and an annual growth rate of 16.6%. As for the editions, these have grown by 8.9% since 1985.

Richter himself has said, on multiple occasions, that he finds the prices of his work excessive. “I am startled [by the record prices], even though it’s nice, good news. The sum, however, is something shocking. It is incomprehensible, as incomprehensible to me as Chinese or physics,” he told the German newspaper Die Zeit in 2015.

Numbering System

Richter’s work is well documented. His works have all been numbered since 1962, and his official database at gerhard-richter.com gives meticulous information about each work, along with auction prices and whereabouts, if publicly accessible.

The Gerhard Richter Archive was established in Dresden in 2006, and the artist himself has published two catalogue raisonnés. “People feel comfortable when buying, because everything is so carefully documented and they can analyse the market for the particular work they are considering,” Westphal says.

And Richter’s long-term dealer, Marian Goodman, has managed sales skilfully, Westphal adds: “She and Anthony d’Offay in the past did a great job placing works in museum collections.” Indeed, around 40% of Richter’s total output is in museums today.

The abstracts are the most expensive works, but for auction house specialists, works from the Kerze [candle] series are the “holy grail”, according to Katherine Arnold, Christie’s co-head of Post-War and contemporary art, Europe. Richter painted 24 images of these flickering white candles—one of which featured on a Sonic Youth album cover—in the early 1980s and initially none sold. Today the highest price for a candle piece is an astonishing £10.5m ($16.5m), set at Christie’s London in 2011, and Westphal says she has heard of a private sale at a higher price.

Pitfalls

There is one area which buyers need to be aware of: Richter did not “officially” begin painting before 1962, and indeed does not consider any work produced before 1961—when he escaped from East Germany—to be part of his art. There is, as a result, no market for these pre-1961 works, which rarely appear for sale.

Buyers also need to be aware of condition, notably with his early works, which were made on fine linen canvases and may have suffered damage. “You need to check the condition carefully in the early works,” Westphal says.

• Data by Art Market Research

UPDATE: At Art Basel on 11 June, David Zwirner sold Versammlung (1966) by Gerhard Richard for $20m. According to a gallery statement, the work "hadn't been seen outside of Italy in 40 years and hadn't been on the market for close to 50 years". It was consigned to the gallery by Francesca and Massimo Valsecchi, who are raising funds by the sale of this work for their cultural project in Palermo, the renovation of Palazzo Butera.