After years of talking the talk, the art world appears to now be walking the walk when it comes to improving its green credentials. While artists such as Olafur Eliasson and Sebastião Salgado have long addressed society’s need to face the climate crisis, the arts sector is finally examining its own contribution to it.

One of the highlights of this year’s Venice Biennale is Lithuania’s Golden Lion-winning pavilion presentation, Sun & Sea (Marina). The artists Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte and Lina Lapelyte have brought the beach, complete with sand and sunbathers, to the Arsenale’s military zone in the form of a poignant installation-performance in which singers masquerading as sun worshippers croon warnings of an ecological catastrophe. “People went in thinking they’d only spend five minutes and instead they stayed and came out in tears,” says the pavilion’s curator Lucia Pietroiusti. “What is it that is so stuck in the back of our throats now that even a small gesture can release?”

Harvesting ice at Nuuk Port and Harbour; Greenland Photo: Kuupik V. Kleist/KVK Consult © 2018 Olafur Eliasson

Pietroiusti, who is due to speak at an Art Basel talk on the carbon footprint of contemporary art, says her limited budget determined the project’s carbon emissions. “Everything we brought from Lithuania came in one truck,” she says. As the curator of general ecology at London’s Serpentine Gallery, Pietroiusti is keen to embed ecology into all her projects. To avoid being just another “parachuted national pavilion”, she invited locals to participate in the performance, brought in a Venetian cast to take up the baton from the original performers after the opening week, and drafted in the designer Benjamin Reichen from the collective Abäke to create the catalogue with assistance from inmates at the Santa Maria Maggiore correctional facility.

When it comes to sourcing materials and tools, Pietroiusti was surprised that participants were not simply sharing items such as ladders or screwdrivers. “Wouldn’t it be great to be the facilitator of [a sharing network]? The problem is that the Biennale is a competition… you’re competing for boats, resources, etc,” she says. When we talk about reducing a pavilion’s carbon footprint, Pietroiusti says we should be asking “how pavilions can collaborate to collectively make meaningful reductions, changes and forms of sharing”.

The mountain of waste left over from the Biennale is another major issue. Jane da Mosto, the co-founder and director of the non-profit We Are Here Venice, says that although organisations such as Rebiennale collect and reuse materials, the lack of storage facilities in Venice means that “recycling is fairly limited to the immediate demand for materials as the exhibitions are dismantled and all the rest is thrown out. It’s crazy that, between them, the Biennale and the local administration can’t [do more] to address and limit wastage and promote reuse”. She says there are many empty spaces, including the Galeazze Est of the Arsenale, that could be used to store materials until they can be recycled or donated.

Waste not want not

Like biennials, art fairs generate a lot of waste. So much so that the US artists Lauren Was and Adam Eckstrom, who moonlight as art installers, created a cottage from art fair detritus. When the Smoke Clears: The Fair Housing Project, part of their ongoing Ghost of Dream collaborative project, is made from five years’ worth of leftover crates and scraps of carpet. Was stresses that the piece is not meant as a statement against art fairs, explaining that their work actually looks at the ephemera people use to achieve their dreams. “Art fairs have paid our bills both through sales and by installing work at them for the past ten years,” she says.

Waste is “the dirty side of the business that no one wants to talk about”, says Andrew Stramentov, a director at ROKBOX, a UK startup that has developed reusable and recyclable art crates. “Trucks spirit away all the rubbish left over from installing the stands before visitors arrive,” says Stramentov, who is also due to participate in the Art Basel talk.

When asked about the carbon footprint of the Art Basel fair, its global director Marc Spiegler does not mince his words. “Let’s put our cards on the table: it would be impossible to stage an art fair or biennial without having some kind of impact on the environment. By definition they are not the most environmentally friendly events because they require travel from people and works of art.” He asks: “How can you be carbon-neutral in an environment that is urgent and ephemeral in nature?”

Ghost of a Dream, Fair Housing Project (2015-16) © Etienne Frossard

Despite this conundrum, Art Basel has a working group that analyses the environmental impact of its stable of fairs and looks for ways to counterbalance it. Working towards this goal, the fair does more digitally to reduce its paper consumption; recycles and donates materials used in its Messeplatz project in Basel; has banned food vendors from using single-use plastics; and from 2020, the Basel fair will swap HQI lighting for energy-saving LEDs.

While Spiegler admits he does not necessarily encourage galleries to reduce their carbon footprints because “we want to avoid telling our clients how to do business”, he says they are experimenting with how to do this in their own way. Catherine Bottrill, the head of the creative green programme at the UK charity Julie’s Bicycle, says getting senior leadership onboard is the key to business involvement: “Commercial [endeavours] are always driven by cost imperatives, even the ones that are not cash poor. But if senior management gets [the importance of sustainability], they feel that as a business it’s a no-brainer.”

For long-time Art Basel exhibitors Pace Gallery and David Zwirner, being eco-friendly is engrained in their corporate cultures. According to a spokeswoman at Zwirner, the dealership became the first commercial gallery to receive LEED Gold Certification when it opened its Annabelle Selldorf-designed space in New York in 2013. Pace’s new flagship New York gallery, which is due to open in September, is expected to meet LEED Silver Certification.

A spokesman for Pace says the gallery has also made its day-to-day activities more environmentally friendly by “supporting [its] shipping partners’ crate recycling efforts, investing in branded, reusable water bottles” for staff, and banning plastics. “We collectively recognise that each small action adds up and raises the level of consciousness for our entire community.” For Art Basel, Pace has encouraged its London and Geneva teams to use ground transportation to get to Basel and all its staff to use public transportation while there. Additionally, it is showing works in its inventory on iPads instead of handing out printed materials, and was careful to ship only works needed for the stand while recycling packing materials for reuse at the end of the week.

Crates and packing materials represent the most tangible form of transport-related waste. ROKBOX is exploring the uses of multiuse plastics, including biodegradable bubble wrap, and the art transport, handling and storage company, Momart, has created a recycling scheme where 90% of packing materials, mostly wood crates and foam, go to local schemes to be turned into beehives or padding for children’s playgrounds.

Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing Supported by Bloomberg; Installation: Bankside; outside Tate Modern; 2018 © 2018 Olafur Eliasson Photo:Charlie Forgham-Bailey

Momart’s director Alan Sloan says: “The environment is very high on our agenda, not least because, from a practical perspective, it saves us money to be efficient, but there is also responsibility of principle to be as environmentally friendly as we possibly can.” As well as ensuring that its buildings are energy-efficient, Momart regularly upgrades it older trucks for newer, more fuel-efficient ones with lower emissions. And it is now looking into investing in smaller, electric vehicles for local jobs around London.

There is still much more that the art world can do to clean up its act, but those advocating for the environment within the sector are finding they are less often pushing on a closed door. “It’s a hopeful time. People feel obliged to change their ways,” Stramentov says. “The art world isn’t as carnivorous as people think it is.”

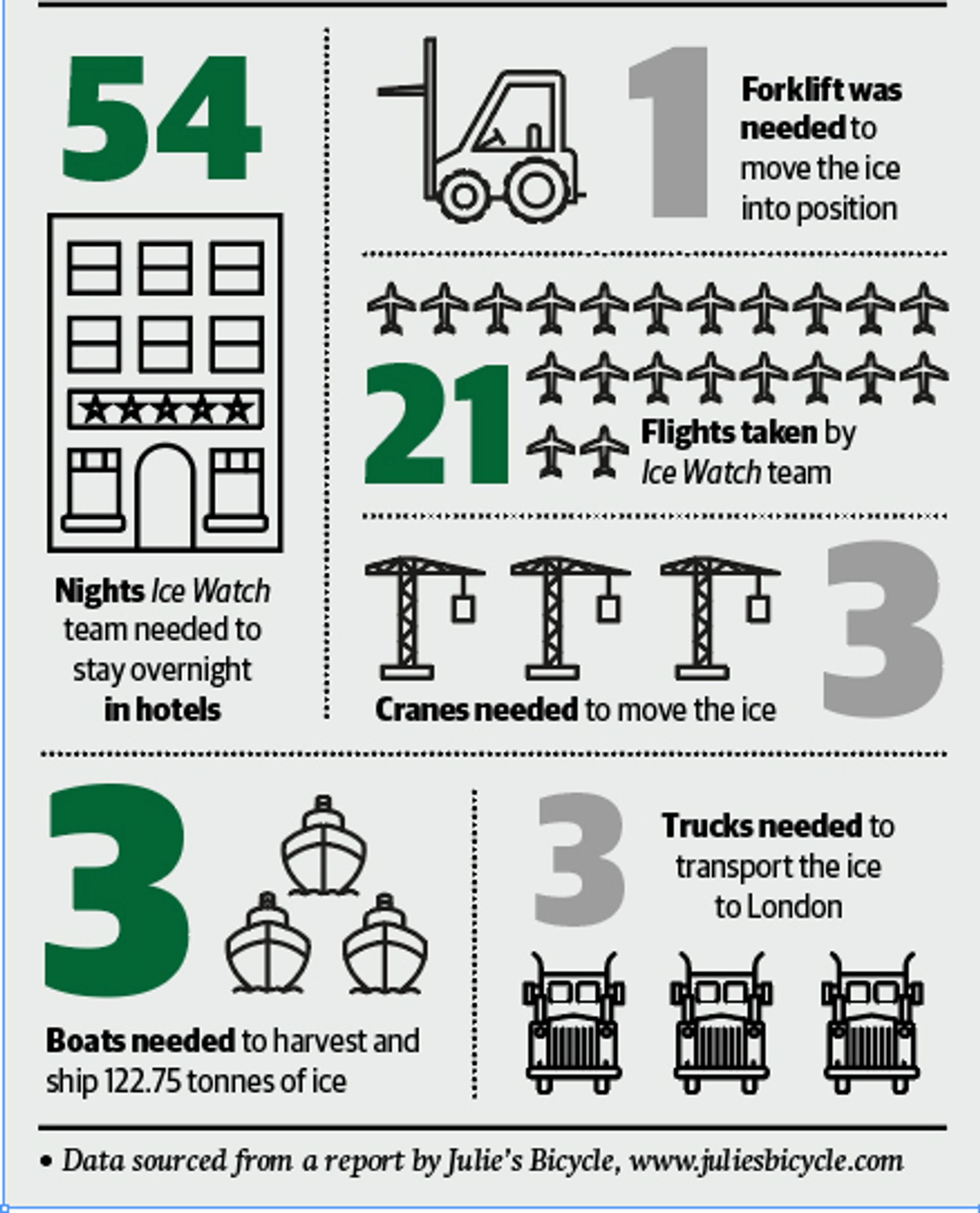

Ice Watch in Numbers

Artist Olafur Eliasson brought 30 ice chunks from Greenland to London last December for his climate change work, Ice Watch. A report on the project’s carbon footprint, by the charity Julie’s Bicycle with co-operation from the artist’s studio, states that its CO2 emissions totalled 55 tonnes. Here we breakdown the practicalities of bringing the large-scale installation to London.

• The Carbon Footprint of Contemporary Art, Wednesday 12 June, 5pm-6pm, Hall 1, Messeplatz